Before I begin ladling out the deserved praise, allow me to lodge a minor kvetch at the complaint department.

To wit, the title of Tricia Romano’s scrappy, compendious oral history of The Village Voice—The Freaks Came Out to Write—does the book a disservice. A play on the Whodini song “Freaks Come Out at Night,” The Freaks Came Out to Write scans but misleads, evoking an image of mutant hippies tumbling out of a decal’d Volkswagen bus in a giant puff of pot smoke, or an invasion of mole people.

But The Village Voice shared almost nothing in common with the Berkeley Barb or the other underground rags in their venereal splendor. It was not an offspring of 60s counterculture, soaked in psychedelia and sporting Che Guevara berets. It began earlier, sprouting through the cracks in the crumbling sidewalk, and attracted the sort of hardworking, crusading, nicotine-stained, neurotic recruits who once made New York great.

It Takes a Village

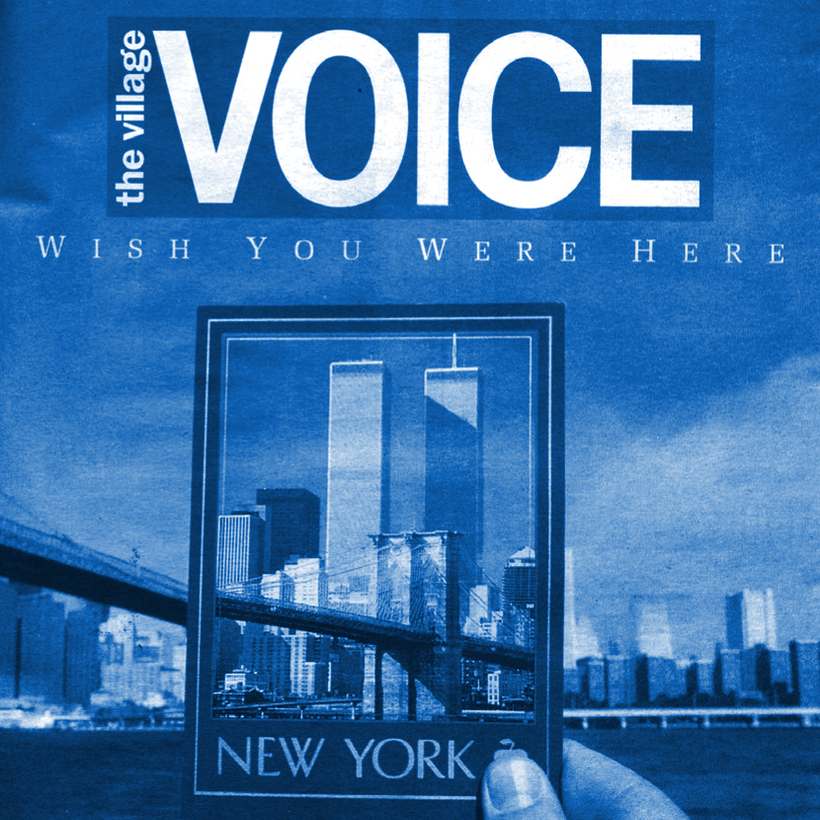

The first issue of The Village Voice flapped into being in 1955, the same year that William F. Buckley Jr. brought forth upon this continent the conservative National Review (signaling the cultural and political divide that would sharpen ahead). The Village Voice was founded by two men who had served during World War II—Daniel Wolf and the future psychoanalyst Edwin Fancher—with their friend and fellow war veteran Norman Mailer lending a little swash and buckle to the start-up as a modest investor and immodest columnist.

In the foreword to The Village Voice Reader (1963), Wolf declared that the paper appeared in response to the shoulder-hunching conformity of the Cold War and McCarthyism and the milquetoast mewings of the intellectual elite. “The best minds in America—radical and conservative—were repeating themselves,” Wolf wrote. “Up and down the countryside the elect of the Ivy League had taken flight into the reality of the conventional church, the community organization, the lawn mower.”

This impatience with the bland platitudes of prosperity, conformity, psychoanalysis, and suburban lawn care produced a newspaper resistant to mush from all sides and committed to hard-smacking personal expression and slangy vernacular over the lofty lighthouse views and embalmed prose of slick magazines, highbrow quarterlies, and, most of all, The New York Times, then at the height of its ecclesiastical sonority.

“The best minds in America—radical and conservative—were repeating themselves. Up and down the countryside the elect of the Ivy League had taken flight into the reality of the conventional church, the community organization, the lawn mower.”

In what began as a local coffeehouse of first-person journalism, certain Village Voice features became reader favorites: Jules Feiffer’s cartoons of black leotard dancers in ponytails and jittery liberals twitchy with status anxiety, the artful vignettes of Bill Manville’s Saloon Society column (which read like downtown’s answer to The New Yorker’s Long-Winded Lady), John Wilcock’s Village Square column, Jerry Tallmer’s theater reviews, and guest-star drop-ins from the likes of Kenneth Tynan, TV’s Steve Allen, composer John Cage, and the eternal butterfly of love Anaïs Nin.

For better or worse, it was Mailer who infused The Village Voice with a fighting attitude that punched above its weight. Mailer, then at a tense juncture in his writing life, besieged by suspicions that he had squandered the success and promise of The Naked and the Dead and was sinking into the middle ranks, used his column in The Village Voice to recharge his batteries and épater la hip bourgeoisie. He nominated Ernest Hemingway for president. He memorably trashed the groundbreaking Waiting for Godot without having seen it, then recanted after he did, his then wife informing him in the cab ride home, “Baby, you fucked up.”

It was Mailer’s presence in the smudgy pages that signaled that The Village Voice wasn’t merely the town crier of Greenwich Village but had national bullhorn potential. He soon left the paper because of its bedeviling typos and because he considered it too tame for his radical appetites, but his relationship with Village Voice readers would define the feedback loop of the enterprise.

Thumbing his nose at them by titling his column Quickly: A Column for Slow Readers, he got on their nerves, they got on his, and the heckling from the wise guys in bleachers made the Village Voice Letters section the liveliest and wittiest weekly gripe session in journalism, and proof that there was so much untapped talent in the amateur ranks that just needed a place to turn pro. The Village Voice would become that place. (It was a letter of recommendation from Mailer to editor Dan Wolf that helped me get my big head through the door.)

For better or worse, it was Norman Mailer who infused The Village Voice with a fighting attitude that punched above its weight.

An oral biography of an institution is far more daunting than one of an individual because the cast list is far larger, extending over decades, and there isn’t a central figure—an Edie Sedgwick, a Truman Capote, a George Plimpton—to provide the magnetic focus. Romano does an impressive job of keeping this Tower of Babel from wobbling too much, preserving the testimonies of a huge host of writers, editors, photographers, staffers, and bystanders sassing and contradicting each other, sharing fond memories while others gnaw on old grudges with beaver gusto.

Covering an immense tract of concrete terrain spanning decades and multiple cataclysms (the riotous 60s, the Stonewall rebellion, the AIDS epidemic, the Central Park Five, 9/11, the crack plague), the chapters remain brief and bouncy, like hopscotch hops, the sound bites so snappy they’re more like snack bites.

So many minor descriptive details rang true, such as the way the music editor and Dean of American Rock Critics, Robert Christgau, rocked back and forth when he read a writer’s copy, as if davening. And even with my cellular experience of Village Voice history and lore, I learned a number of curious things about former colleagues and comrades, such nuggets as editor Ross Wetzsteon putting his fist through a window over a birthday cake, Nat Hentoff standing at the urinal like Superman, hands on hips, and ace investigative reporter Wayne Barrett mockingly modeling a dress in the office after Karen Durbin was promoted to top editor. Not exactly vital details, but once they’re inside your head, there’s no getting rid of them.

As the newspaper grew thick with advertising and developed mini-fiefdom departments devoted to film, theater, politics, pop music, press criticism, and book reviewing (a chapter on the excellent late, lamented Voice Literary Supplement—the V.L.S. for short), the place ran on multiple cylinders that ensured a crackling vibrancy but also produced a pressure-cooker atmosphere on the premises.

The vaunted Letters section evolved from a bulletin board where readers and contributors sniped at each other from the hedges into an intramural pummel match. As in The Godfather, where war needed to be waged between families every 5 or 10 years to get rid of the bad blood, long-simmering antagonisms between different camps—the “Stalinist feminists” versus the “white guys”—would erupt into thrilling bouts of acrimony.

One chapter in the book retails the ruckus caused by a Feiffer cartoon that used the n-word to make a point about prejudice that had the poor timing of appearing in the paper’s first Gay issue. A group of writers and editors published a letter disassociating themselves from the cartoon, the free speeches fired back, and the feuding continued in the pages and in the offices for an entire summer, keeping everybody frisky.

Another eruption occurred in 1986 over the critic C. Carr’s rhapsodic tribute to the transgressive performance art of Karen Finley, one of whose pieces was titled “Yams up My Grannie’s Ass.” Pete Hamill, an upper-echelon white guy with fans everywhere, was inspired to file a retort titled “I Yam What I Yam,” which some failed to find amusing, none more so than Finley herself. “I thought about writing a letter to the Voice, but every time I sat down to write ‘I Never Put a Yam In My Butt,’ I’d think, ‘But what if I had? SO WHAT?’” This was a question many of us asked ourselves in the 80s.

Whenever one of these Cobra Kai attacks broke out in print, Nat Hentoff was sure to be involved, he of the Superman pee stream. He was never more vexatious to much of the staff than when the fight was over abortion, with Hentoff, the First Amendment champion, adopting a pro-life position that many believed was not just a personal conviction but a crafty provocation.

Hentoff had a knack for bringing everything to a boil while retaining a merry equanimity that could be infuriating if you weren’t in the mood for it. Or, as Laurie Stone puts it so poetically, “People like Mailer and Hentoff, they were just ordinary, old-school, male fuckheads.”

The book’s chapters remain brief and bouncy, like hopscotch hops, the sound bites so snappy they’re more like snack bites.

However difficult, contentious, or unpopular a particular fuckhead might be, it took major infractions to get ejected from the clubhouse, as in the notorious case of the jazz writer and arts critic Stanley Crouch. The man embodied amplitude, initiating a low rumble into every room he entered. He had an expansive bear-hug personality and a capacity for brilliant, self-perpetuating, one-sided expostulating that could leave listeners rooted to the spot until their legs began to give.

Though capable of great generosity and camaraderie, Crouch indulged too heartily an irascible side that was part of his persona. He didn’t feel bound by many of the proprieties that prevailed and liked to pepper the pot. I remember chatting with Crouch at the Village Voice mailboxes once when he uncorked, “The thing about some of these feminist bitches is … ,” and I went temporarily deaf, a protective measure useful at such moments.

It was one thing for Crouch not to keep his mouth to himself, but it was his being unable to keep his hands to himself that was uncondonable. The chapter “Stanley Was Just Red-Eyed and Ready to Go” details his brief, inglorious, pugilistic career at The Village Voice. He had roughhoused with and bullyragged a number of Village Voice writers and editors over the years, but on one occasion he went berserk, punching hip-hop writer Harry Allen in the jaw (Crouch hated hip-hop and rap with Godzilla fury) and trying to drag him into the utility closet to finish him off behind closed doors.

Allen extricated himself, but the red line had been crossed, and at that point Crouch had to go. He sobbed outside the editor’s office at the news but later mused that the best things that ever happened to him were being hired and fired by The Village Voice. “After I left the Village Voice, that’s when my career took off.” True enough. He climbed into a higher division of public intellectual, certified by the MacArthur “genius grant” he received in 1993. He left a lot of ill will in his wake, but success is an excellent absorbent.

In the afterword to The Freaks Came Out to Write, Romano, a former Village Voice columnist, reveals that the impetus for doing the book was attending the Village Voice reunion held downtown in 2017. It was a reunion that doubled as a memorial service, as a roll call of “the names of those who had passed on were read from the stage” while a slideshow of Village Voice veterans present and deceased played on a rear screen. Not every name was met with reverence. When Mailer’s was read aloud, a smattering of boos and hisses rent the noisy hubbub, a fine way to treat a founding father.

The roll call went on so long that the mood in the room became rather testy. At one point a brief, shouty exchange broke out between a Village Voice alumnus hogging the mike and audience members impatient for her to get on with it, and I confess moments like this made me feel almost cuddly inside. It was like being home all over again.

I left the reunion feeling that it represented The Village Voice’s last hurrah, but now we have this book, thanks to Tricia Romano, and it’s the best last hurrah of all.

James Wolcott is a Columnist at AIR MAIL. He is the author of several books, including the memoir Lucking Out: My Life Getting Down and Semi-Dirty in Seventies New York, which features a chapter devoted to his novice years at The Village Voice