At the moment, it appears that the once mighty Sports Illustrated has been forced into retirement after the magazine appeared to publish articles by fake writers, complete with A.I.-generated author bios and photos. Shortly thereafter, Arena Group lost its license to publish S.I., and there were mass layoffs. (Note to any company thinking of trying this: A.I. is very good at detecting other A.I.)

It’s a pathetic end for a 70-year-old icon that historically published only real—and great—sportswriters such as Dan Jenkins, George Plimpton, Rick Reilly, Selena Roberts, Frank Deford, and even Kurt Vonnegut.

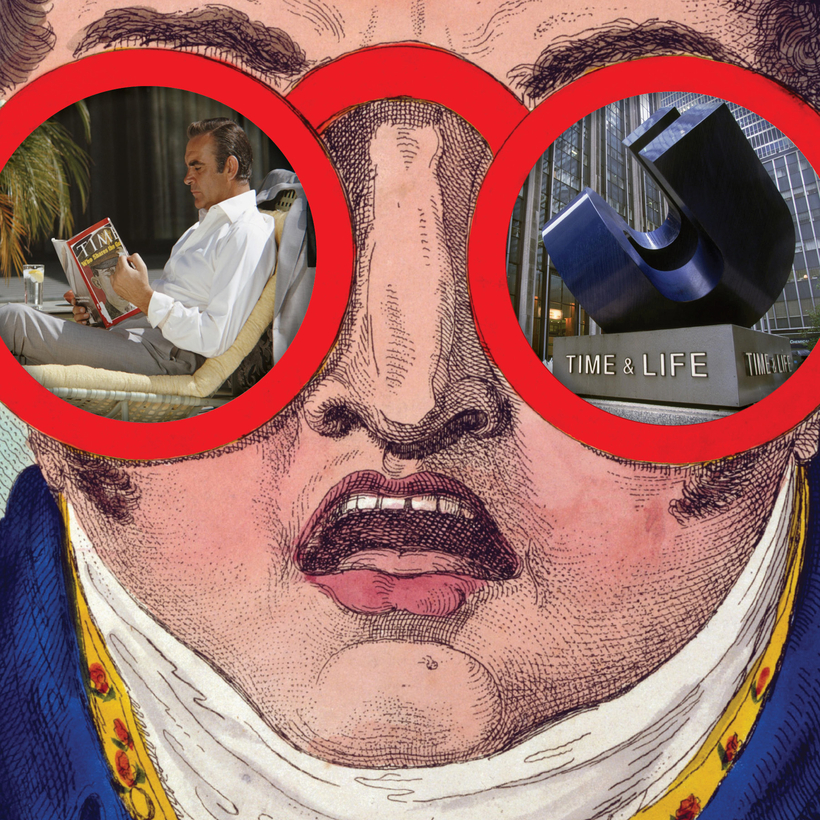

Perhaps sadder still, S.I. managed to outlive by five years the company that created it: Time Inc. Once the largest and most profitable publishing company in the world, its final day was January 31, 2018, when workers on hydraulic lifts began covering the logo on its New York headquarters with that of an Iowa-based company: Meredith Corporation.

When giants fall, there are always stories left behind. After Time Inc., they are tales of vast income and reckless spending—of arrogance, insularity, missed opportunities, indifferent management, and more twists than a 1960 school dance.

Let’s start with the company’s golden age, long before cell phones and computers, when Time magazine had a circulation of four million, and another Time Inc. title, Life, was read by 1 in every 10 Americans. When Sports Illustrated earned more than $90 million from a single Swimsuit Issue. And when People, the human-interest publication in Time Inc.’s arsenal, was the most profitable magazine on earth.

Those fine days were especially so if you worked in editorial. Managing editors, who oversee the day-to-day operations of a magazine, were princes (nearly all were men), and the floors they occupied at Time’s 1271 Avenue of the Americas headquarters were their sovereign state.

Salaries led the industry, and if you were in favor, bonuses could be generous. Karl Taro Greenfeld, who worked at both Time and S.I. back then, remembers a bonus of $100,000. In a recent essay in the Los Angeles Times, he calculated that his yearly, inflation-adjusted income was more than he made as a writer for the Showtime series Ray Donovan.

Time Inc., he wrote, became a company that “excelled” at waste. With torrents of cash pouring in weekly, there wasn’t much attention paid to how much was going out. Nearly everybody who was there at the time has a story about profligacy: a farewell lunch for 50 at Lutèce, then the city’s priciest restaurant; every seat on a Concorde flight to Europe being occupied by someone from the company headed for the Olympics; a top editor in Paris sending an underling back to London to fetch a necktie he’d left in his hotel room; and Kanye West being hired to perform at a private party.

Ordering food for employees working after hours isn’t uncommon at many companies—pizzas or deli platters are the norm. But at Time Inc., every Tuesday, a copyboy would make the rounds of senior editors’ offices to drop off two bottles of liquor and several bottles of wine. Once a weekly issue was put to bed, they would retire to a restaurant on the ground floor for drinks and steaks. Those left behind got wine, beer, and cookies. If you lived out of town and were working late, you could stay at a hotel … any hotel.

There was a lot of drinking, both during and after work. Writing about her days at Time, Maureen Dowd used Mad Men as a point of reference. There was, she says “an aura of whisky, cigarettes, four-hour sodden lunches, and illicit lunches.” No wonder Time Inc. placed No. 5 in a 1970s edition of The 100 Best Places to Work in America.

Time Inc. became a company that “excelled” at waste. With torrents of cash pouring in weekly, there wasn’t much attention paid to how much was going out.

If you were assigned to one of Time Inc.’s foreign bureaus, you got housing, a car (often with a driver), club memberships, private-school tuition for your kids, and a cost-of-living allowance. For traveling editors, business class was expected, first class preferred. Nobody, though, could touch the flight status of the editorial director, John Huey, who was ferried to his home in South Carolina every weekend by private aircraft at an exorbitant cost to the company.

Expense-account limits, if you even had a limit, were magnanimous. Spending $25,000 in a month wouldn’t get you into a bit of trouble. Some were even handed back their expense reports to “do over” because they were too low. As one editor was told, “Nobody here ever got fired for spending too much money.”

Then there were the staff writers, whose contracts were sometimes worth $1 million or more. In 1990, Reilly was given an assignment to play golf courses around the world. There was no budget, naturally. Reilly flew off to Scotland, Ireland, South Africa, Dubai, Thailand, Indonesia, Japan, Australia, and Los Angeles—18 courses in all. He returned three weeks later with a well-traveled golf bag and a $50,000 expense bill, only to find that his editor had left the magazine, and his replacement was “a tennis guy.” Reilly was never asked to write the golf story, and he never did.

If you had an expense budget, you spent it all for fear of getting less in the next billing period. Reilly’s was $10,000. After a long day of shadowing Gary Sheffield, of the Milwaukee Brewers, he found himself $800 short, and Denny’s was the only place open for dinner. “We said, ‘Give us your best bottle of wine,’ but they only had the little airline ones, so we ordered 23 of those. Then we ate ourselves sick, and Gary took home enough food to feed all his friends. And the bill still only came to $200.”

When you’re treated like royalty long enough, you come to think of yourself as an aristocrat. At Time Inc., that led to provincialism—promotions nearly always came from within—and arrogance. “Our feeling was that we were better than the rest,” says someone who worked there for 20 years. “We didn’t need anyone else.”

That might explain why big opportunities were missed. When owners of the fledgling network ESPN, based in the small city of Bristol, Connecticut, came looking for investment, they were turned away. Later, Hearst bought a 20 percent stake in ESPN for $170 million, now said to be worth $10 billion. An early overture from TMZ was also dismissed for fear that the gossipy Web site would tarnish the golden People brand, says a former executive who was there. TMZ is now the leading destination for Hollywood and pop-culture news, both online and on television.

In 1990, though, Time Inc. made one investment they shouldn’t have, and it proved to be a perilous one: they bought Warner Communications in a $15 billion stock swap, creating the largest media company in the world.

On paper, it looked like an ideal marriage: the world’s largest content producer hitched to a company that owned HBO and other cable channels, sports teams, and the world’s largest cable provider, Warner Cable. It might have worked, too, if either side had tried harder to understand the other’s business. But they didn’t.

The beginning of the end for Time Inc. and many legacy print companies came in 1995, when the Internet opened its gates to commerce. A year earlier there had been only 2,500 Web servers in the entire world. The following year there were 75,000, with more coming online daily. (Today there are more than a billion.) Services such as CompuServe, AOL, Yahoo, and Netscape ushered people onto the Web.

Soon, subscribers from the bloated magazine circulations—inflated to help compete with TV for advertising—began to turn away from ink on paper to spend time online. Time Warner’s answer was Pathfinder, a mash-up of content from Time, Money, S.I., People, and other properties. Individual titles were forbidden from using their own domain names, so no people.com. Pathfinder shut down five years later, having burned through $120 million. From then on, most of the Time magazines seemed to lag behind their competitors in digital.

Nobody could touch the flight status of the editorial director, John Huey, who was ferried to his home in South Carolina every weekend by private aircraft at an estimated cost to the company of $650,000 a year.

With revenue shrinking rapidly at a rate of a billion dollars in a single year, spending cuts were requested. John Huey’s private flights were grounded forever, but in the end it was too late.

There followed a disastrous series of mergers. In 2000, after losing $80 billion on the deal, Time Warner sold to AOL, flush with cash from its 30 million subscribers. Don Logan, the C.E.O. of Time Inc., ended up calling the Internet “a black hole.” AOL Time Warner certainly was, losing a record $99 billion in 2002.

The next in line was AT&T, with $100 billion to spend in 2016. It was another record disaster, and they would dump the company for $85 billion in 2020, but not without first spinning off the Time Inc. magazines.

Meredith, the publisher of Better Homes & Gardens, picked up the magazines in 2017 for $2.8 billion, replacing the Time Inc. brand with their own. (Full disclosure: I was editorial director at Meredith a decade before the Time Inc. acquisition.) Meredith mostly wanted People and InStyle, and sold Time to a U.S. billionaire, Fortune to a Thai billionaire, and S.I. to a licensing company, which licensed it to another, the Arena Group, which killed it via A.I.

However, the jinx endured. InStyle went out of print, newsstand sales and ad pages at People declined, and Meredith itself was sold at a loss to Dotdash, a digital-media company.

That shouldn’t be the last word on Time Inc., though. For nearly 100 years, its magazines defined the world for Americans, in words and pictures. Life showed us the first horrifying pictures of the Kennedy assassination. Time covers told us who, or what, was important that week. And the exceptional writers and photographers at Sports Illustrated always seemed to capture the perfect frozen moment, distilling the soaring, culture-shaping drama of athletics into something more permanent than a television broadcast.

Despite all the wild times and bad deals, Time Inc. was the greatest magazine company that ever was, or ever will be.

Mike Lafavore is a New York–based writer who served as the founding editor of Men’s Health magazine and menshealth.com