In the early 1980s, Hill Street Blues writer Anthony Yerkovich was reading The Wall Street Journal when he came across a startling statistic. According to the newspaper, one-fifth of all the unreported income in the U.S. passed through a single city: Miami.

“If you’re doing a show,” Yerkovich says, “you want to pick an area that’s got a lot of shit happening all the time.” Dade County clearly fit the bill, he says, with a crime rate 40 times the national average at the time and so much cash that there were 14 pages of banks listed in the Miami phone book. Miami was a “modern-day Casablanca,” Yerkovich said in Time, “a sort of Barbary Coast of free enterprise gone berserk.”

While doing research, he discovered that criminal forfeiture allowed the federal government to seize a defendant’s property and ill-gotten gains following a conviction. Yerkovich envisioned underpaid cops being given access to the kind of expensive boats, cars, watches, and clothing required for them to pass as high-level players in Miami crime circles. He saw the opportunity to create complex, morally conflicted detectives who get so buried in their undercover work that they lose a sense of their true selves, as well as what’s real and what’s not.

Then there was MTV, the upstart cable channel whose fast-paced editing and visual storytelling was changing the way viewers were consuming entertainment.

It was these three seemingly unrelated elements that Yerkovich pulled together to create Miami Vice, the 1980s cop series that brought feature-film ambition to the small screen. Sopranos creator David Chase described the show’s impact as “a sea change.”

Miami Vice actually started out as a film script named “Dade County” but became a television series when NBC committed to do it as a two-hour pilot. The project, however, almost ran into a wall when Yerkovich told network execs that he wanted Don Johnson to play the lead role of world-weary, good-old-boy detective James “Sonny” Crockett. Having closely observed the journeyman actor’s interactions at a popular Hollywood restaurant, Yerkovich was certain Johnson had the perfect combination of charisma and confidence to carry the series.

“Don had a riverboat-gambler quality that really worked for the part,” Yerkovich says. “I knew viscerally—and instinctively—that I was right.”

NBC executives were against casting Johnson, pointing to the string of failed pilots starring the “six-time loser.” Undeterred, Yerkovich asked to read the scripts for those pilots, after which he concluded that the writing, not the actor, was the problem. The network gave in.

Next, Yerkovich and his collaborators cast Philip Michael Thomas as Crockett’s partner, Ricardo Tubbs, a smoldering New York cop out to avenge his brother’s death at the hands of a drug dealer.

Sopranos creator David Chase described the show’s impact as “a sea change.”

The script wound up in front of Michael Mann, a former Starsky & Hutch producer, whose directorial debut, the 1981 neo-noir crime thriller, Thief, used strong visuals and an electronic score by Tangerine Dream. Intent on never returning to television, Mann changed his mind after reading Yerkovich’s script.

“It was vivacious, audacious, irreverent,” Mann told The Washington Post. “It was something I’d been interested in doing for a long time: pump a contemporary rock and roll sensibility into a police-ier genre.”

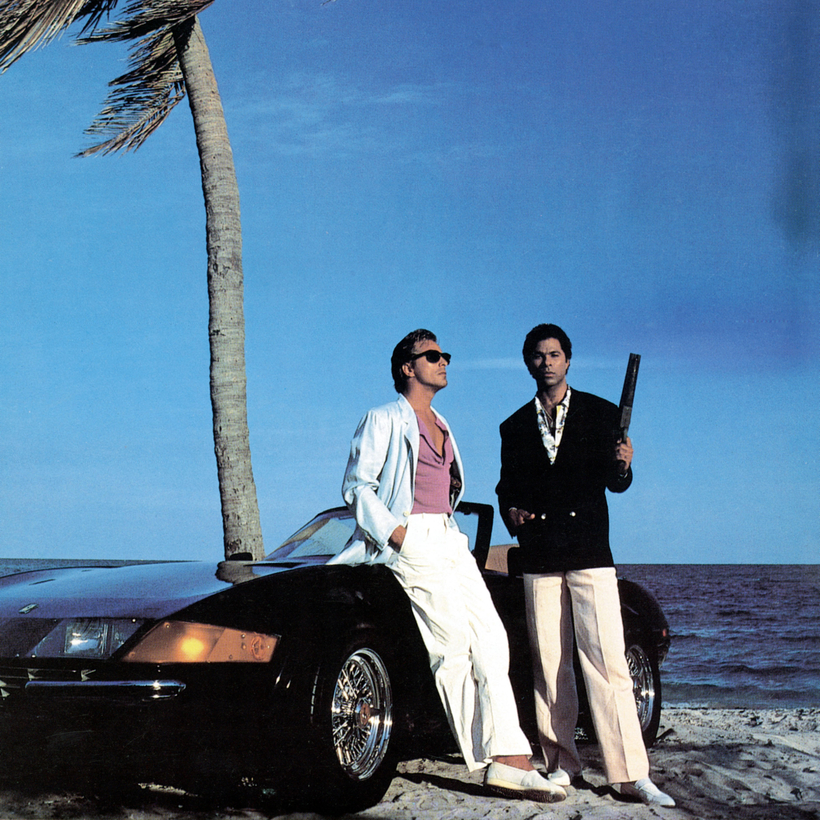

Mann agreed to produce, but only if he was given total creative control, which meant overseeing everything: story development, casting, and locations, music, editing, wardrobe, even the show’s color scheme of pastels set against the black, silver, and chrome of luxury sports cars and high-rise apartments. Issuing decrees such as “No earth tones” and “No cop drives clunkers,” Mann didn’t direct a single episode yet became an auteur in the world of television drama.

“We take like one-tenth of one percent of the objective reality of Miami and that’s what we render,” Mann said.

The visually dazzling pilot, which cost more than $1 million to make, debuted in September 1984. Opening with the driving electronic beat of Jan Hammer’s theme and a quick-cut montage of palm trees, flamingos, beaches, and speedboats, Miami Vice was designed to stop viewers from flipping channels. “We wanted it to look and sound different from anything else on the air,” says Kerry McCluggage, the executive from Universal who shepherded the project.

“I’m not sure people even knew what was different, but they felt it,” says Thomas Carter, the former White Shadow star, who directed the pilot. “We were creating this from nothing and telling a story with limited dialogue that required the audience to lean in and get drawn into the picture.”

Carter memorably used Phil Collins’s “In the Air Tonight” to carry a key sequence. Later episodes were based on everything from the lyrics to Glenn Frey’s “Smuggler’s Blues” to a story Mann heard from a cop who’d pulled him over for speeding.

Despite uniformly positive reviews, Miami Vice was buried in a moribund Friday-night time slot and didn’t gain much traction until it went into reruns the following summer. By the start of the second season, it was a ratings success and a cultural touchstone. Johnson’s signature look—Ray-Bans, a T-shirt under a suit jacket with the sleeves pulled up, and a few days’ stubble—was widely imitated. One company even marketed a facial-hair trimmer called the Miami Device.

Issuing decrees such as “No earth tones” and “No cop drives clunkers,” Mann didn’t direct a single episode yet became an auteur in the world of television drama.

Viewers started planning their Friday nights around the show, whose guest stars included musicians Frank Zappa, Little Richard, and James Brown; not-yet-famous actors such as Bruce Willis and Julia Roberts; and pop-culture figures that ranged from N.B.A. legend Bill Russell to Watergate co-conspirator G. Gordon Liddy.

Civic leaders in Miami had feared the show would make their city look like a crime-infested cesspool. But when it became a hit, they began reshaping what was then a vacation spot for elderly snowbirds into a place that better reflected the series.

“When we got there, the Art Deco district was somewhat threadbare,” Yerkovich told The New York Times. “Now it’s up to its Ray Bans in espresso.”

Mann left the day-to-day running of the show after a few years to direct Manhunter and develop his equally stylish Chicago-based cops-and-mobsters series, Crime Story.

During its five-year run, Miami Vice set the stage for The Sopranos, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, and other shows that defined television’s second golden age.

“People that had been doing television … had had a very boring, delimited perspective on what you could do,” Mann said. “The idea was to do television with a bunch of people who’d never done television before.”

Josh Karp is the author of A Futile and Stupid Gesture: How Doug Kenney and National Lampoon Changed Comedy Forever and Orson Welles’s Last Movie: The Making of The Other Side of the Wind