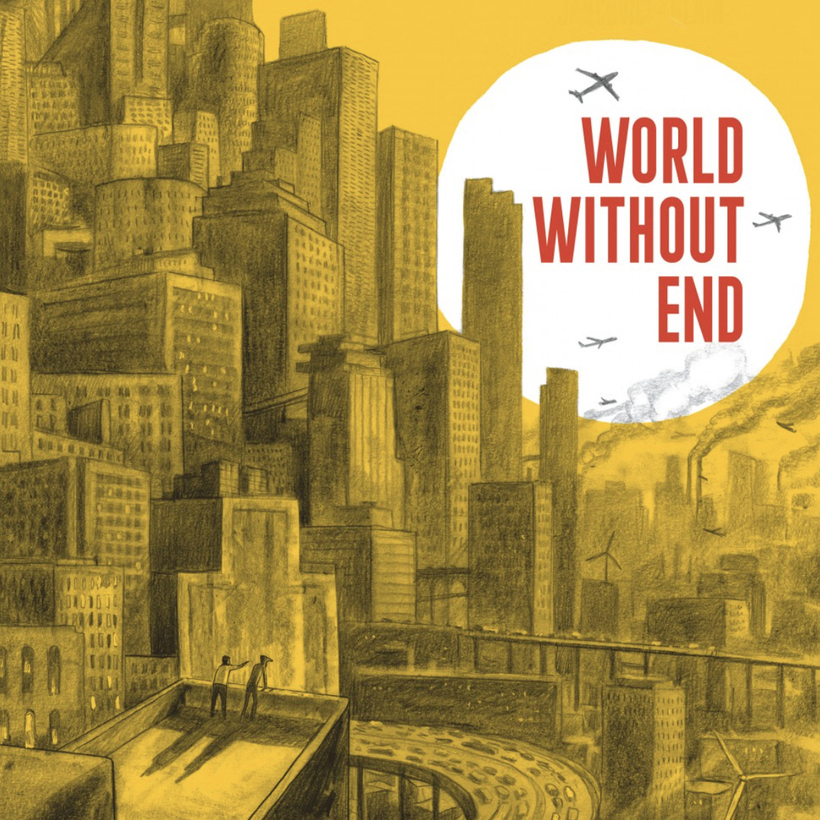

A book about climate change written in the form of an extended comic strip would not seem an obvious bestseller. But then along came World Without End.

An unusual collaboration between Jean-Marc Jancovici, a French engineer turned environmental guru, and the graphic artist Christophe Blain, it has sold more than a million copies in its original French version since it was published three years ago, making it the country’s most successful book in 2022. Translations into twenty or so languages including Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese and Portuguese followed — and it is finally coming out in Britain.