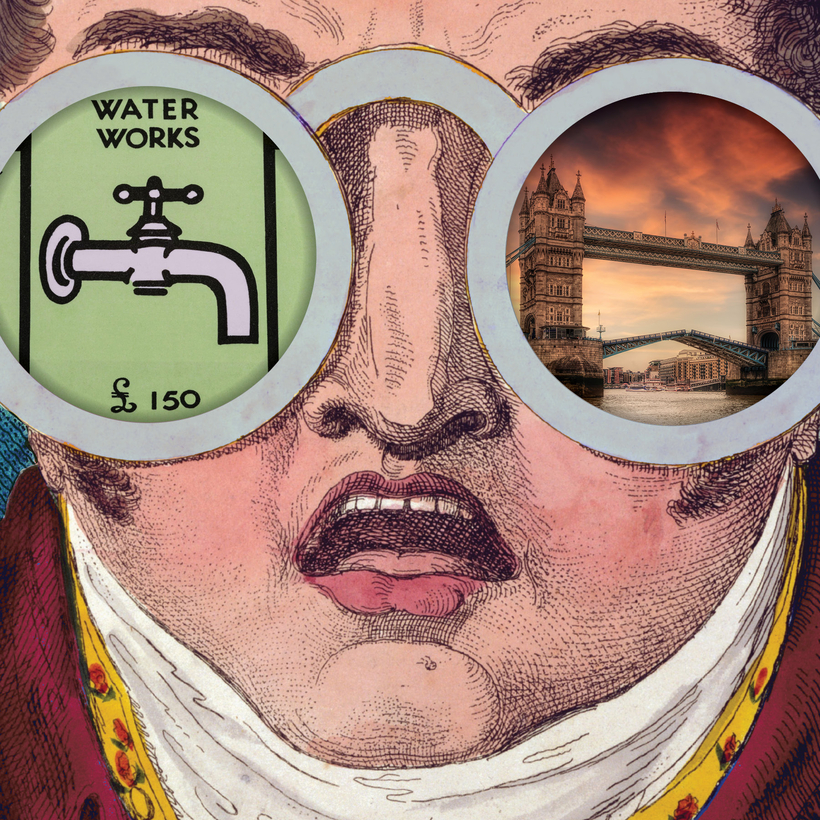

Players of the property-dealing board game Monopoly have never greatly loved the utilities—the water and electric companies, which sit dour and gray among the more colorful Park Place–type investment opportunities. Ambitious players consider the utility companies boring and worthless, even if a few steadier, less flashy contestants regard them as surprisingly O.K. investments that pay modest dividends.

In real life, though, utility companies—those that deal in water in particular—are potentially terrific financial assets. Literally everyone needs water, and the infrastructure for getting it to people’s taps is so cumbersome that supplying the stuff lends itself to an actual monopoly.