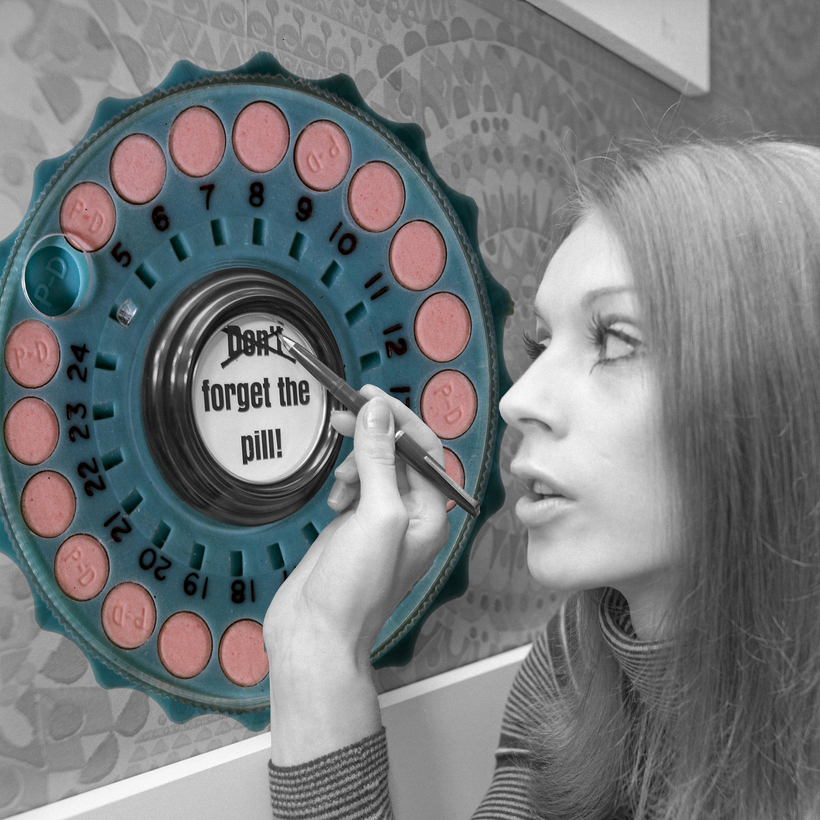

At one point in history, the pill was heralded as a medical marvel, a way to unshackle women from an unwanted future. For female equality and independence, no invention of the 20th century has been more life-changing; as Gloria Steinem said, “Not everyone with vocal chords is an opera singer. And not everyone with a womb needs to be a mother. When the Pill came along we were able to give birth—to ourselves.”

But if you’re a young woman scrolling through TikTok today, chances are you’ll soon come across a video on the pill—if you haven’t already—suggesting its reputation has gone the way of Diddy or skinny jeans. There are very few things that have left-wing hippies and right-wing incels in agreement, but this seems to be one of them.

On the one hand, there are the cheerleaders of the ever growing wellness trend, who bemoan the effects of putting “unnatural” hormones into your body. Thousands of TikTok videos feature not just granola-munching vegans but also everyday—usually liberal—young women explaining why they’d never touch the pill, or, if they have, why they are giving it up.

One video features a woman claiming that “birth control is considered a level 1 carcinogen … which is the same as cigarettes.” This is likely a (completely false) extrapolation of data released by the Cancer Research UK charity, which says that “taking the … pill slightly increases the risk of breast cancer compared to people who do not take it,” but that there is no noticeable increase 10 years on from going off the pill, and the pill actually lowers women’s risk of ovarian and womb cancer. Plus, its link to cancer is obviously far, far lower than cigarettes.

Some of these videos raise known side effects, such as weight fluctuation or skin changes, but others are either grossly exaggerated or patently untrue, making unfounded proclamations about the pill’s negative impacts on fertility or the heightened risk of blood clots. Younger girls are replying to the videos with statements like “I’m so scared to start the pill one day,” followed by crying emoji. (This particular TikTok comment was liked nearly 20,000 times.)

According to the Food and Drug Administration, the risk of blood clots from the pill is less than 0.1 percent—significantly lower than for those who are pregnant or post-partum—and there is no evidence of long-term risk to fertility. “There are many myths about the side effects of contraception that are inaccurate or not founded in science,” says Washington, D.C.–based ob-gyn Jayme Trevino. “For example, effects on fertility…. However, serious complications from contraception are rare.” Trevino adds that misinformation about contraception “is something I encounter regularly.”

Chances are you’ll soon come across a TikTok video on the pill suggesting its reputation has gone the way of Diddy or skinny jeans.

As for the right wing, viral TikTok videos—sometimes to the tune of hundreds of thousands of views—peddle similar messaging, just for different reasons. In a widely shared video, Brett Cooper, of the Daily Wire, a media company founded by the conservative political commentator Ben Shapiro, condemned birth control not just because it causes women to have trouble getting pregnant but because it can change whom you’re attracted to.

This subject was also discussed in one of Shapiro’s own videos, where his guest claimed women on the pill prefer more feminine faces. The idea that a woman’s partner preferences change when she’s on and off the pill may be a popular theory on the conservative corners of TikTok, but studies on the subject have found no such link.

There are very few things that have left-wing hippies and right-wing incels in agreement, but this seems to be one of them.

Over the past 10 years, women’s use of the contraceptive pill has decreased from 47 percent to 27 percent in England. While we haven’t seen as marked a decrease in the pill’s popularity in the U.S., the ongoing battle over abortion could make the stakes much higher. Since the overturning of Roe v. Wade, in 2022, one in three American women now live in a state with abortion restrictions, and in a country with high rates of teen pregnancy, misinformation on one of the most effective forms of contraception—and on a platform most teens are addicted to—is alarming.

These viral videos are already having a real-life impact, with more and more young women instead turning to fertility-awareness methods, or FAMs—long known to Catholics as the “rhythm method” and these days practiced by younger people through apps such as Natural Cycles—for birth control. While these can be effective, they require women to regularly track a number of factors, such as their temperature and cervical mucus, therefore increasing the risk of unwanted pregnancy.

Natural Cycles was even sued in its origin country of Sweden after 37 out of 668 women who sought an abortion at a Stockholm hospital reported that they’d been using the app for birth control, and in the U.K., the Advertising Standards Authority ordered the company to remove an ad because the figures being shared were based on the perfect user rather than on the typical one, for whom, Planned Parenthood says, FAMs are about 77 to 98 percent effective—a pretty large window, if you consider that’s between 2 and 23 out of 100 couples who will get pregnant each year using FAMs. (Natural Cycles won the Swedish suit and was cleared by the F.D.A., though the agency puts the app’s failure rate at 6.5 percent, which is much higher than the pill’s.)

In England, the National Health Service, the country’s public health-care system, has officially called out misinformation about birth control on TikTok as being at least partially responsible for the reduced numbers of women taking the pill. And in Scotland, doctors have similarly pointed to social media’s negative portrayal of the pill as a reason why abortions are up 19 percent year over year, with a noticeable increase among teenage abortions.

One video features a woman claiming that “birth control is considered a level 1 carcinogen … which is the same as cigarettes.”

With far-right videos going so far as to classify the pill as “abortionist,” many now fear for the pill’s future. This is especially true in the U.S., where the upcoming election threatens to put Trump—whose stance on birth control is a wild card at best—back in the White House.

The challenge for young women is that control over their own bodies is a key part of their freedom, but it’s difficult to know what to believe when surrounded by so much misinformation. Compounding the issue is the negative reputation of medical professionals for not always taking women’s concerns seriously.

Women have often been ignored when it comes to the pain involved with the insertion of IUD contraceptives, for instance, with a recent Duke study revealing that 97 percent of TikTok videos shared on the subject were negative, often highlighting the pain of insertion or removal. Similarly, while polycystic ovarian syndrome—or P.C.O.S., as it’s often referred to—officially affects 6 to 12 percent of women of reproductive age, it’s estimated that 70 percent of women go undiagnosed. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that young girls are turning to one another online for advice.

The problem is, social media is far from a balanced platform when it comes to medical concerns. While doctors on TikTok do share valuable, informed content, these videos are often overshadowed by sensationalized posts made by people with no medical knowledge that nonetheless go viral. Thoughtful, nuanced discussions about contraception and health care get buried, leading women to be constantly exposed to alarmist, unfounded content.

The pill is far from perfect, but it remains a good choice for many women who now see it unfairly demonized. (A similar thing happened with the coronavirus vaccine, which filled some social media users’ feeds with misleading or very fringe cases.) When anecdotal scare stories dominate the conversation on TikTok, they can seem universal, potentially discouraging important dialogues with health-care professionals—and putting more young women in dangerous positions as they accidentally turn back time to the 1950s.

Flora Gill is a London-based writer