I first met Edward Jay Epstein at a birthday dinner for a mutual friend in 2013, 10 days before the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination.

On my way to work that morning, I had listened to a radio interview with the author of a new book about the Warren Commission. My only previous exposure to the subject was the Oliver Stone movie JFK, so I knew less than nothing.

At some point during the meal, the subject of national security came up. Sensing an opportunity, I deployed a couple of facts from the interview to make a sweeping declaration about America’s history of intelligence failures. Ed, who was sitting a few places down, suddenly leaned forward to say that I might be interested in reading something he had just written.

The next day, waiting in my inbox was an EPUB document titled “The JFK Assassination Diary.” I soon learned what Ed had the good manners not to lord over me at dinner: namely, that in 1966, as a graduate student, he interviewed every member of the commission but Warren himself, and that his thesis, which concluded that the investigation had been insufficiently thorough, became a best-selling book that decisively shifted public opinion.

He returned to the subject now and again—to report for The New Yorker on New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison’s supposed break in the case, or to interview Yuri Nosenko, the ex-K.G.B. agent who claimed to have been Lee Harvey Oswald’s case officer—but unlike many writers drawn to the assassination, Ed quickly moved on to other topics, including counter-intelligence, the war on drugs, the diamond industry, the movie business, and, finally, his own improbable life.

I soon learned what Ed had the good manners not to lord over me at dinner: namely, that in 1966, as a graduate student, he interviewed every member of the commission but Warren himself.

In the headline for his obituary, The New York Times called Ed a “stubborn skeptic,” which is half right. It’s certainly true that he made a career of questioning accepted narratives—the charge that the police were systematically killing off the Black Panthers, for example, or the widely held belief that an engagement ring is a good investment.

But Ed was not stubborn. He was always ready to change his mind when the facts changed. In the late 1970s, after a rigorous and independent forensic analysis, the House Select Committee on Assassinations traced each of the bullets fired at Kennedy’s limo back to Oswald’s rifle. Ed, alone among the commission’s critics, pronounced himself satisfied.

Sometimes, it was the absence of information—or “the dog that didn’t bark,” as he liked to say, quoting Sherlock Holmes—that led him to revise his original thesis. He had made the case, first in Legend: The Secret World of Lee Harvey Oswald and then again in Deception: The Invisible War Between the KGB and the CIA, that Nosenko was a likely double agent. But no subsequent defector ever confirmed it, so Ed came to accept that Nosenko, whatever else he lied about, had probably not been sent by the Kremlin after all.

It’s certainly true that he made a career of questioning accepted narratives. But he was always ready to change his mind when the facts changed.

Ed and I met for lunch every few months. He continued to send me whatever he was working on, and sometimes I would offer a suggestion or two. On one occasion, this led to my first mention—and deletion—in the paper of record.

About halfway through his relentlessly negative review of How America Lost Its Secrets: Edward Snowden, the Man and the Theft, Nicholas Lemann wrote, “Epstein clearly wants to leave readers with the impression that Snowden remains in Russia as a result of a deal…. He repeatedly hints that he has reason to be more certain about his conclusion than he’s able to say in print; for one tantalizing example, among the names on a list of people he thanks … is the outgoing secretary of defense, Ash Carter.”

After I notified the editors of my civilian status, they cut the reference and added this correction: “The Ash Carter mentioned … is an editor at Esquire magazine, not the former defense secretary.”

Most authors would have fired off a letter to The New York Times Book Review, furiously disputing each and every line, but Ed, in a virtuosic display of intellectual jujitsu, expressed only his appreciation for “the perceptiveness of Nicholas Lemann’s thoughtful and fair review”:

“For example, he is correct in suggesting that my preferred reporting method is to dig into underlying documents, including those produced by the American intelligence services and their Congressional oversight committees, rather than to credit reporting that simply repeats the narrative of the perpetrator of an alleged crime.”

As for my own small part in this drama, he said, in an e-mail, “I am forever grateful to Lemann for getting me on front page of review and elevating you to the prominence you deserve.”

To the reading public of the last half-century, it must have seemed like he was always scuffling with some Cold War eminence or grandee of the New York media elite, but, really, Ed never lost his cool, or his sense of humor. In fact, the more I got to know him, the more I was struck by the many dissimilarities between the man and the byline.

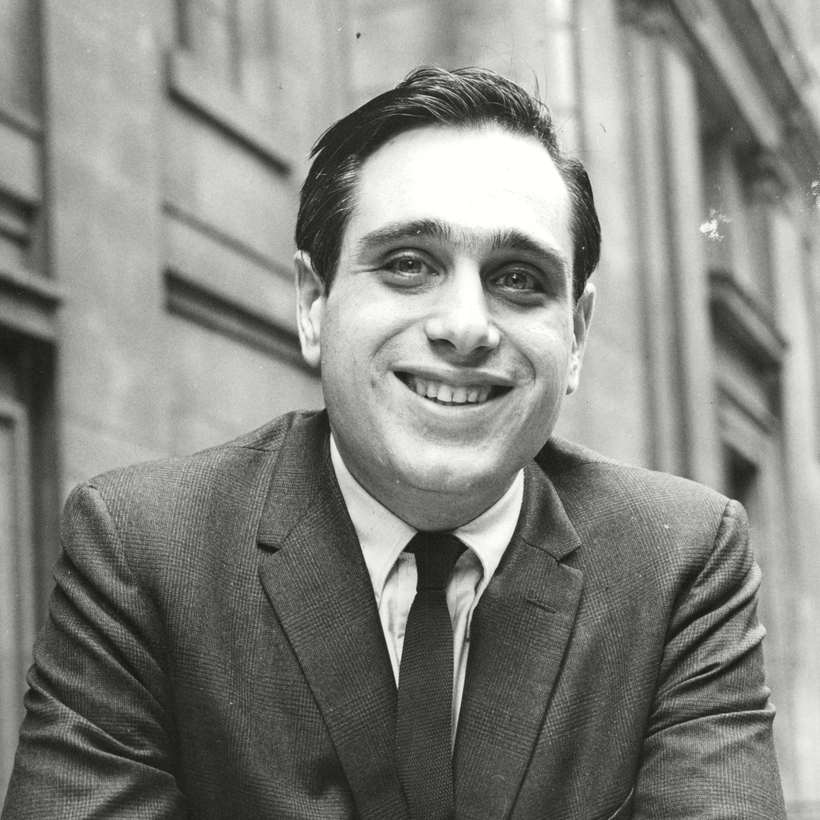

Edward Jay Epstein was an outsize and controversial figure. To mention his name in certain contexts was to start an argument. He tended to be photographed in half-lit rooms, seldom smiling. Like a character in a real-life spy novel, he would suddenly surface in Tehran, or Lahore, or Moscow. And he was frequently spotted at the Army and Navy Club, in Washington, D.C., across the table from former C.I.A. counter-intelligence chief James Jesus Angleton, the arch-villain of a thousand conspiracy theories.

Ed Epstein, meanwhile, was polite and easygoing and started every conversation by asking after your family, in his unmistakable Brooklyn accent. He was a regular guest at, and host of, Manhattan cocktail parties, where the only intrigue is a little publishing gossip. And though he was certainly disciplined—I’m told that he sat down to write every morning after a cup of coffee and an apple—Ed Epstein never took himself too seriously.

Ed never lost his cool, or his sense of humor. In fact, the more I got to know him, the more I was struck by the many dissimilarities between the man and the byline.

Ed had just turned 88 the month before he died. So why were some of his friends, me included, so shocked when we heard the news? It’s because Ed’s mind was still operating at the very highest level, right up to the end.

The last time I saw him, in September, over lunch at Orsay, on the Upper East Side, I asked Ed what he thought about the recent news that one of the Secret Service agents assigned to Kennedy’s motorcade now claimed that he had picked up a bullet from the back seat of the open-top Lincoln Continental and placed it next to the president’s stretcher in Parkland Memorial Hospital.

Ed, though he had surely been expecting this question, did not have a ready-made answer. First, he considered the possibility that the agent might be misremembering or simply lying. Then, drawing on his deep familiarity with the details, Ed explained what—if the agent was in fact telling the truth—this revelation would and wouldn’t change about our understanding of the event. Just knowing Ed made me smarter, though even with a pile of open books in front of me, a chat bot, and all the time in the world, I could never hope to equal his awesome intelligence.

Ed, who was trained by some of the 20th century’s greatest social scientists to analyze human affairs at the level of the organization, didn’t really believe in heroic individuals. But he was one to me.

Edward Jay Epstein was born in 1935 in New York. He died on January 9

Ash Carter is a Deputy Editor at AIR MAIL and a co-author of Life Isn’t Everything: Mike Nichols as Remembered by 150 of His Closest Friends. He is currently editing a collection of Edward Jay Epstein’s best writing