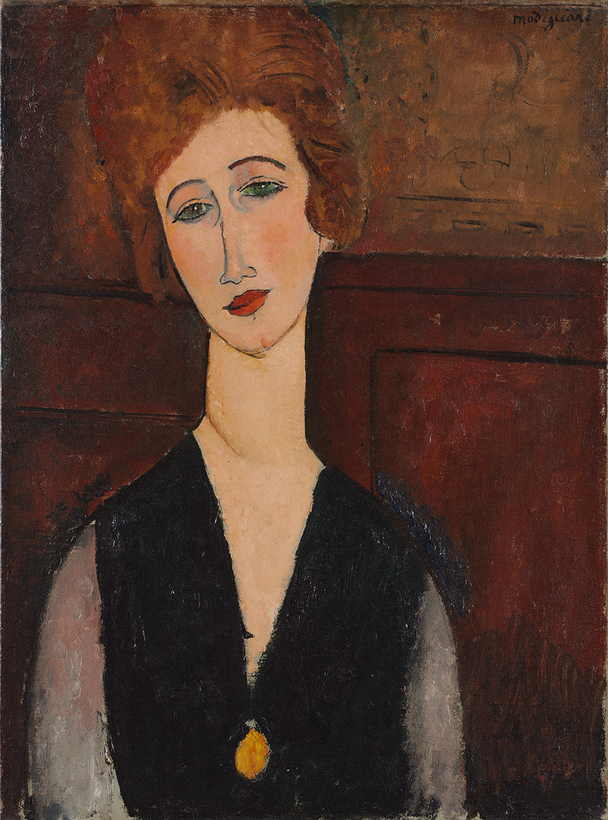

Can Amedeo Modigliani save Johnny Depp? Having emerged damaged but technically victorious from his legal dispute with Amber Heard—his former wife—Depp now finds himself essentially excluded from the kind of mainstream Hollywood cinema from which he derived his considerable wealth and legions of fans. With far fewer options on the table, he has now opted to direct Modi, a movie about the Italian painter who was a key figure—if largely unsuccessful during his lifetime—in the Parisian avant-garde before and during W.W. I. In a grace note, Depp’s film finds a small role for Al Pacino, who back in the 80s had tried and failed to get his own Modigliani film off the ground.

No doubt Depp is attracted to, and perhaps sees himself as, this archetypal bohemian. Modigliani’s life included relentless substance abuse, a string of intense love affairs, a struggle for acceptance by the artistic establishment, and—one thing that Depp has managed to avoid—an early death (in 1920, at 35), from tuberculosis. Depp’s movie is in fact an adaptation of Dennis McIntyre’s 1978 play, Modigliani, which looks closely at the painter’s difficulty making money from his art.