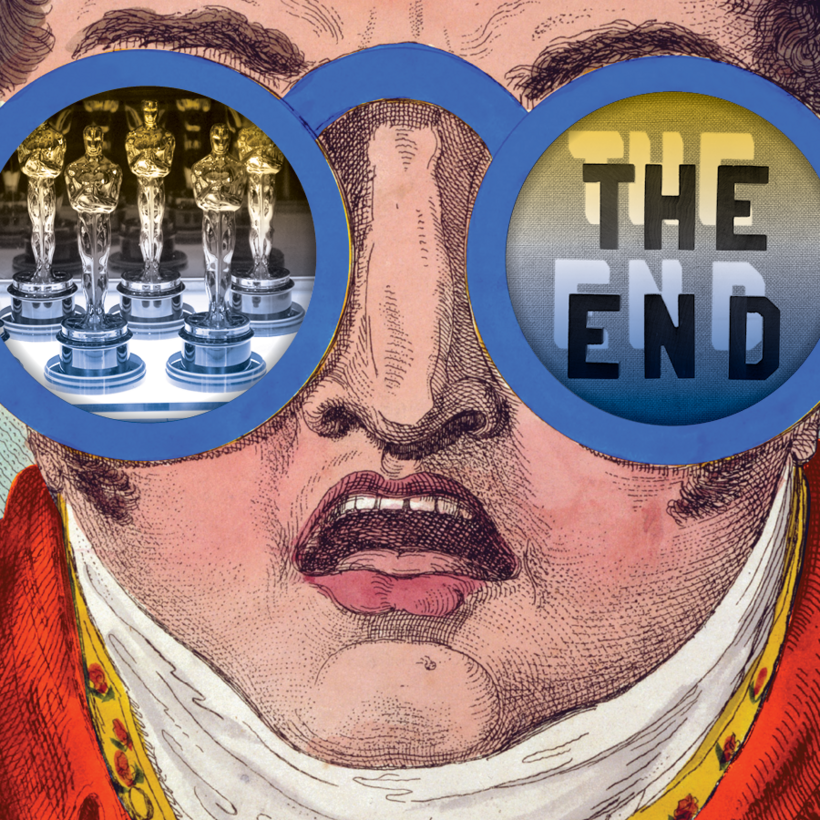

The best picture of the year may no longer be eligible for Best Picture of the Year.

In accordance with the Academy’s recently announced eligibility rules for diversity and inclusion, starting next year all best-picture nominees must satisfy two of the following four standards: