Toward the end of Commando, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Bill Duke go toe to toe in the ultimate motel fight scene. Duke: “You scared, motherfucker? Well, you should be. ’Cause this Green Beret’s going to kick your big ass.” Arnold: “I eat Green Berets for breakfast. And right now, I’m very hungry.” Rae Dawn Chong, like us, watches agog from the periphery: “I can’t believe this macho bullshit!”

If, paraphrasing the great Miss Jean Brodie, macho bullshit—one-inch ponytails, punching snakes, half-speed crotch kicks—is to your taste, Nick de Semlyen, the editor of Empire and author of Wild and Crazy Guys: How the Comedy Mavericks of the ’80s Changed Hollywood Forever (2019), lays on an all-you-can-eat feast in The Last Action Heroes: The Triumphs, Flops, and Feuds of Hollywood’s Kings of Carnage.

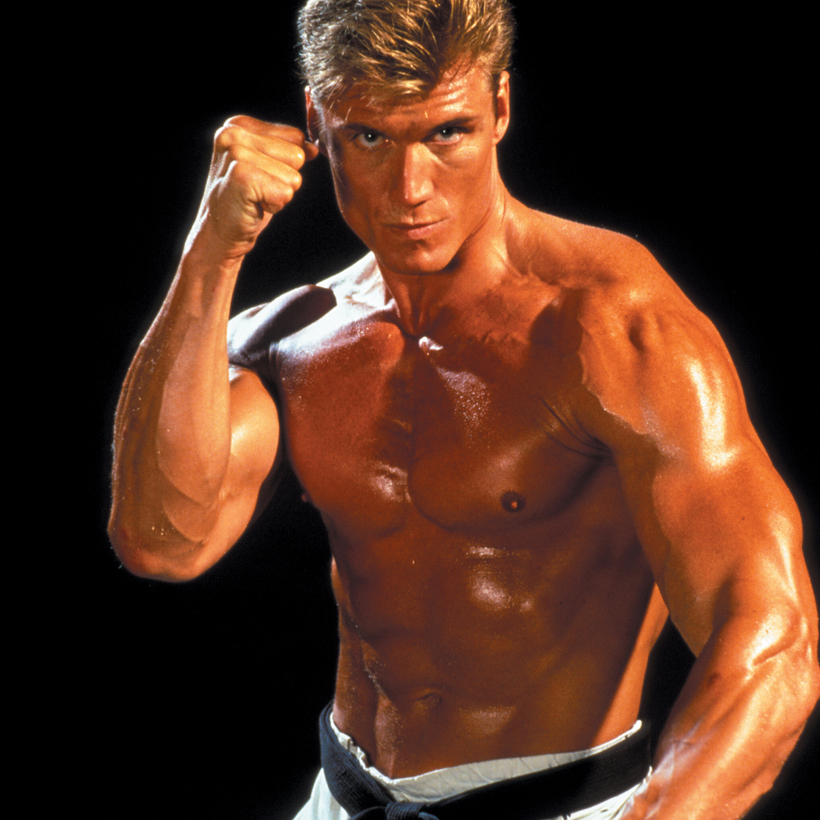

De Semlyen’s action-star pantheon features Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Bruce Willis, Chuck Norris, Dolph Lundgren, Jackie Chan, Jean-Claude Van Damme, and Steven Seagal. The eight-hander format might have undone The Last Action Heroes were it not for its deft, hilarious, overlapping weave of anecdotes and detail.

In the beginning, there was humility. A decade before Rocky, Stallone moonlighted at the Central Park Zoo: “Not too many people ever have the thrill of seeing lions taking giant leaks.... Let me tell you, they’re accurate up to 15 feet, and after a month of getting whizzed on, I quit.” An early turn Off Off Broadway saw him in Picasso’s Desire Caught by the Tail: “It’s the only play that Picasso ever wrote, and for a reason, because it was horrible.” One of his first screenplays, Cry Full and Whisper Empty in the Same Breath, was, in his own appraisal, “180 pages of garbage.”

Arnold’s six-step “Master Plan” was on the nose: “1) become the greatest bodybuilder in history 2) learn English....” (In service of these goals, he had “plastered his bedroom walls with posters of scantily clad musclemen, causing his parents to panic, fearing he was gay.”)

Lundgren traded his Fulbright fellowship at M.I.T. for Grace Jones and Studio 54. (Quentin Tarantino’s and Roger Avary’s first screen credits were as production assistants for his workout movie, Maximum Potential, for which their tasks included cleaning up “an acre” of dog shit.)

Yet nothing tops Van Damme’s attempts to break in (at times, literally). His film-festival pitch entailed “scamper[ing] around, approaching anyone who looked important, and shouting, ‘Look at this!’ before performing high kicks and jumps in front of them.” He once drove to Stallone’s mansion and tried to scale the wall. The police were called. His excuse: “I just want to do karate with Stallone.” Van Damme’s persistence paid off in the form of his Hollywood debut as “Gay Karate Man” in something called “Monaco Forever” (running time: 28 minutes).

The retelling of Van Damme’s later “discovery” is surely too good to be true: “[He] was entering a restaurant. Menahem Golan was exiting it. As usual, the former thought with his feet. His right leg flashed up at lightning velocity, arcing around and coming to a rest two inches above the head of Cannon [Films]. ‘Jean-Claude Van Damme,’ he reminded the startled producer. ‘Karate guy.’ Golan told him to call his office the next day.”

There, “without hesitation,” he “whipped off his shirt, stretched himself between two chairs in the splits position (legend would later suggest he also broke entire bricks on his head, though it’s unclear how he got them through security) and began to talk.... Then came Van Damme’s closing gambit, delivered with a simplicity that the producer of Ninja III: The Domination might appreciate: ‘I’m a young Chuck Norris. Maybe one day a Stallone. So, what do you say?’” Golan paid him all of $25,000 for Bloodsport (“Based on a true story,” according to the opening credits).

Nick de Semlyen’s action-star pantheon features Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Bruce Willis, Chuck Norris, Dolph Lundgren, Jackie Chan, Jean-Claude Van Damme, and Steven Seagal.

Such numbers tell something of the octet’s eccentricities. Arnold’s spoken-word count in The Terminator? Its ranking in the 1984 box office? Lundgren’s I.Q.? The quantity of his lines as Ivan Drago in Rocky IV? The proportion of Rocky IV that is montage and of the Marked for Death screenplay that Seagal claims to have rewritten? Van Damme’s days on set as the Predator before his firing? The number of people Rambo kills in the course of the various First Blood installments? (Respectively: 58; 21st, outperformed by Revenge of the Nerds, among others; 160; nine; 30 percent and 93 percent; two; and 552.)

The Last Action Heroes mines, in parallel, an exquisite trove of mercifully unrealized ideas. Stallone as Superman. Seagal as Batman. Stallone’s initial finale for Rocky II, involving the Colosseum and the Pope (playing himself). A mob-meets–Staying Alive version of The Godfather Part III starring John Travolta as Michael Corleone’s son, Anthony, with Stallone directing. (Whether Frank Stallone would have stood in for Nino Rota is unmentioned.)

Duke and Fluffy, an action comedy about “a loyal mutt and a feisty feline,” to be portrayed by Arnold and Bette Midler, “who fall into a machine designed by their scientist master, are transformed into humans, and then team up to retrieve him from criminal clutches.” A “Twins-style” buddy vehicle for Wesley Snipes and Chan as long-lost brothers, to be titled Confucius Brown.

And the you-can’t-be-serious, near-miss passion projects or adaptations: Stallone’s long-gestating Edgar Allan Poe biopic, Arnold as the Count of Monte Cristo, Seagal’s Genghis Khan (“I don’t know that we have anything in common,” Seagal observed, “other than that he was the most brilliant military strategist in the history of mankind”), Van Damme’s Alexander the Great.

No history of the period would be complete, of course, without exploring the making of its classics. The producer Joel Silver is said to have recruited Mark Lester to direct Commando (which, as if lifted from The Player, began life as “the somber tale of an Israeli soldier who had turned away from violence but finds himself forced back into the fray”) at the Playboy Mansion: “‘We were sitting next to each other in pajamas.... He said, ‘My next movie’s going to be called Commando. Want to do it?’ I said, ‘Can I read the script?’ He said, ‘No—if you read the script, you’ll never do the movie.’”

On set, Arnold proposed, regrettably without success, that his character, John Matrix, “chop off an enemy’s arm with an axe, then pick up the severed limb and slap him with it to get him to stop screaming, accompanied by the line, ‘Quit whining!’” Its other one-liners (“Don’t disturb my friend, he’s dead tired,” “Remember, Sully, when I promised to kill you last? I lied,” “Let off some steam, Bennett”) would suffice.

One of the writers of On Deadly Ground, Ed Horowitz, recalls Seagal’s “notes”: “One time he said, ‘I’m seeing six mercenaries in a Sikorsky [helicopter].’ I’m thinking, ‘Why would an oil company in Alaska have any mercenaries? I have no fucking idea. This makes no sense.’ But I just looked at him and went, ‘I’m thinking twelve and two.’ And he just breaks into this smile and points at me.”

At the premiere, Horowitz “turned to his sister midway through and whispered, ‘Debbie, I wrote this movie and I can’t follow it.’” Reflecting on the experience, Michael Caine, who played an evil oil C.E.O., lamented having broken “one of the cardinal rules of bad movies. If you’re going to do a bad movie, at least do it in a great location.”

Off set, we get Van Damme’s musings on his gay appeal (“Maybe they like me because gay people love beauty in general. They have a high level of taste”), his first night with fourth wife Darcy LaPier (“I ate something, but not food. You know what I’m saying”), and which rival could kill him on-screen (Stallone), along with Stallone’s self-deprecating reminiscences, which are memorably selected, despite Stallone having declined to be interviewed.

On Paradise Alley and F.I.S.T.: “I received the worst reviews since Hitler.” How he came to be cast as John Rambo: “I think they were going to lab animals before they got to me.” His feelings about Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot: “The worst film I’ve ever made by far. Maybe one of the worst films in the entire solar system, including alien productions we’ve never seen.”

What’s the moral of The Last Action Heroes? I would venture to say that any book that relates Van Damme’s boast during the filming of Universal Soldier that he “could crack a walnut open with his ass cheeks” perhaps doesn’t need one.

Max Carter is vice-chairman of 20th- and 21st-century art at Christie’s in New York