On La Grenouille’s 45th-anniversary celebration, in 2007, the late Doug McGrath, a very dear friend and talented author, asked my mother: “Madame Masson, why did you open in late December while everyone’s away? Why?” My mother laughed: “I don’t know. It was stupid.”

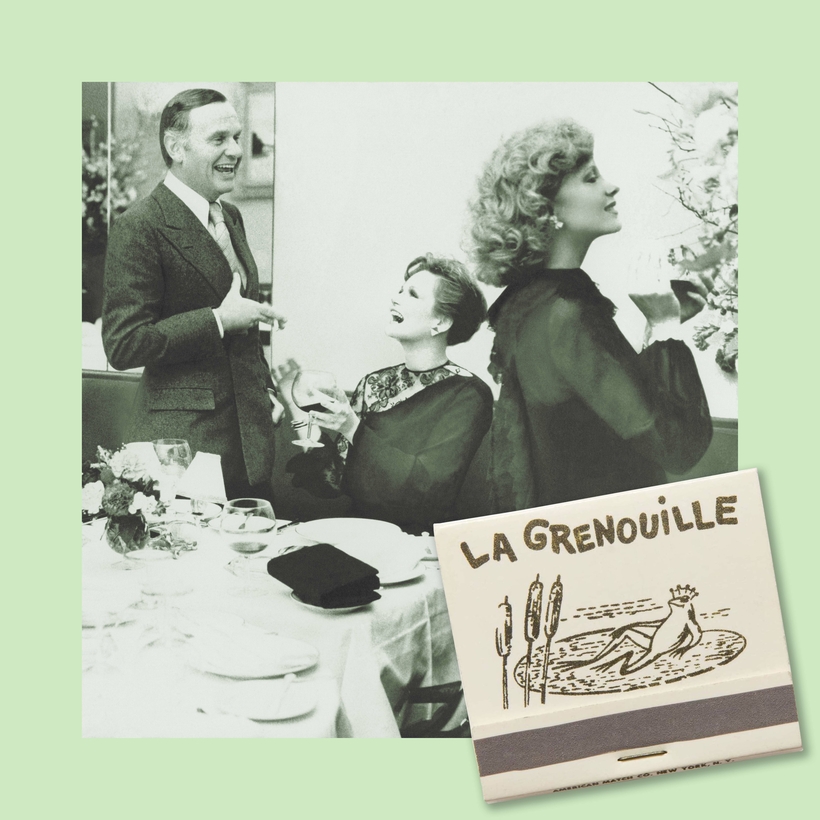

On December 19, 1962, Charles and Gisèle Masson opened a French restaurant with an unpronounceable name, on a snowy night, amid the longest newspaper strike ever to hit New York. There were no backers, no partners, no real money. It was fueled only by elbow grease and purveyors’ credit.

In its tadpole stage the restaurant’s linoleum floor, red vinyl settees, Sheetrock walls, and acoustic-tile ceilings didn’t seem to matter. In time, La Grenouille grew with love and flowers.

But to begin with, there were difficulties. The front room faced south, and the sun shone brightly, too brightly for the comfort of guests seated there. Guests requested the more comfortable rear dining room, leaving the front room empty. Needless to say, having an empty room as an entrance is a serious image problem.

My father tried thicker curtains, but they turned the room dark. No good. Dad liked light. So he bought a large crystal Baccarat vase and filled it with flowers. Sheer curtains and the silhouette of fresh flowers filtered the light, solving the glare issue and improving the décor. Eventually, that first bouquet led to others.

Still, the front dining room remained empty.

The front room was narrower and less comfortable than the back, but the walls couldn’t be moved. Since it was by the entrance and bar, it offered no privacy, and the traffic of guests and servers walking back and forth was unpleasant. David Rockefeller, Brooke Astor, the Kennedys, Edward R. Murrow, Babe Paley and friends, CBS executives, TV personalities, Ed Sullivan, all favored the rear dining room.

Facing a business challenge, Dad resorted to vanity. As did many guests, Murrow liked my father. Dad asked if he would be kind enough to exercise his influence by sitting in the front room for a change. Apparently, the idea amused him.

From that point on, everyone from Walter Cronkite and John B. Fairchild to socialites and influential Madison Avenue personalities all followed Murrow’s lead. Journalists baptized the once preferred rear dining room “the Catsup Room” or “Siberia.” Now everyone requests to dine in the narrow front room. The challenges of front versus back were reversed, causing tantrums, scandals, and seating headaches.

The tide had turned.

A Simple and Quiet Celebration

From the day I left college, in 1974, to help my mother run La Grenouille, I jumped in as best I could, from serving guests to prepping in the kitchen, to arranging flowers in the morning, all the things my father had taught me in order to become a restaurateur.

Mr. Rockefeller, like many guests who patronized La Grenouille when my parents first opened, preferred sitting in the back. The first time I served him, he sat at corner table 17. As a starter, he ordered our classic quenelles de brochet lyonnaise.

When he said “quenelles,” I was taken aback at how he pronounced it. Spoken as a true Frenchman, without the slightest trace of an accent, none whatsoever. I commented on how impressed I was with his perfect diction, to which he answered in perfect French: “J’ai été élevé par une gouvernante française. Ma première langue est le français. l’anglais est venu plus tard. Quand j’avai cinq ans.” (I have been raised by a French nanny. My first language is French. English came later. When I was five.)

Many years, and quenelles, later a group of his friends decided to organize a “simple and quiet” celebration for his 90th birthday. Back then La Grenouille was closed during the summer doldrums and typically wouldn’t reopen until after Labor Day. The only way to host a small intime party for fewer than 100 guests and to prevent the possibility of hurting anyone’s feelings was to plan on skipping accuracy. Mr. Rockefeller’s actual birthday was on June 12, but the party would be thrown late in the summer, while most of his friends were away from the city. Brilliant! Les jeux sont faits!

So on Friday, September 2, 2005, well before La Grenouille would let the public back in, the doors were open for the delivery of a Steinway grand piano to be placed smack in the middle of the front dining room. All the guests would be seated in the back, where David liked it best. This would prevent the childish bickering over who sits where.

A simple dinner entre amis but still reverent to tradition: Black-tie was de rigueur. The menu was simple, consisting of Mr. Rockefeller’s favorite dishes. No amuse-bouches—he never liked those, deeming them superfluous.

The appetizer was a toss-up between several possibilities, but since Bruce Levingston, the gifted pianist, was to perform Mr. Rockefeller’s beloved Chopin for the occasion—including his polonaises—I suggested asperges à la polonaise (steamed asparagus served warm with melted butter and a crumble of bread mixed with chopped up hard-boiled egg whites and yolks and minced parsley).

Naturally, the main course would be his all-time favorite, quenelles de brochet lyonnaise (freshwater-pike mousse poached in a champagne cream sauce, with steamed white rice). The dessert was another classic of French cuisine, oeufs à la neige. (Often confused with île flottante, this dish is prepared by lightly whisking egg whites with fine sugar to a softer-than-meringue density, then delicately rolling them so as to create a silky-smooth surface, setting the oeufs onto a chilled plate with crème anglaise, and finally topping them with angel-hair caramelized spun sugar.)

A simple dinner entre amis but still reverent to tradition.

The entire dinner, from start to finish, flowed with 1989 Dom Pérignon. Then espresso coffee in demitasse cups was served along with a selection of petits fours with far more florentines than langues de chat, tuiles, or macarons. Mr. Rockefeller loved florentines.

Toward the end, Bruce rose from the table. He raised a coupe of champagne and pronounced, “To our dear David.” It had previously been agreed that there would be no long speeches, no speeches at all: “just a toast.” As everyone cheered, a praline dacquoise cake with one candle was presented to Mr. Rockefeller. He blew out the candle to much applause, and with no further ado, Bruce began playing Chopin sonatas.

The evening ran its course smoothly, and exactly, following Mr. Rockefeller’s preference: dine early and get home early. The beautiful party began promptly at 6:00 p.m. and ended at 8:15 sharp.

The streets in New York City before Labor Day were always eerily deserted. For once the black limos queued up easily along East 52nd Street. All the guests had left except for Mr. Rockefeller and Bruce Levingston. As the piano-rental company arrived to pick up the Steinway, Bruce and Mr. Rockefeller shook hands and hugged.

A late summer night, not yet autumn. The deep-blue sky was not too dark. Bruce exited first. and finally Mr. Rockefeller walked out, and then returned quickly to gather the raincoat he had left behind.

I took the coat off the hanger and tried to help Mr. Rockefeller with it. “Non, ça va, Charles. Il ne pleut pas.” (No, it’s O.K., Charles. It’s not raining.) Mr. Rockefeller folded his coat over his arm, and as he walked out, I asked: “May I help find your car?”

He raised his arm in the air saying, “Thank you. It’s right here.”

A yellow cab pulled up and I opened the door. He waved good-bye, saying: “Merci encore!”

Tiny Terror

Table 5-Bar is the very first table on the left, a small one by the reservation desk. It’s easy to walk past it and ignore its existence. The red velvet banquette dead-ends against the coatroom wall. Whenever the maître d’hôtel—whether it was Paul, Jean, Joseph, Armel, or I—would attempt to seat a couple there, it invariably elicited a “Do you have another table?”

Over the years, we’d ask ourselves: Is it because the table is too small? Or is it the wall? Or maybe it’s the mirror? Or is it a bit claustrophobic? Or is it because it’s perpendicular to the wall? Or is it because you are not seen? Yes, that’s probably it! Because in our “to see and be seen” society, the last part outweighs the first.

Nevertheless, while Table 5-Bar is undervalued by most, it is coveted by a select group of artists, poets, and writers. It’s a perch from which you can enjoy the scene safely, like a voyeur, without being caught.

For Bernard Lamotte, the painter who lived above in the second-floor studio years before La Grenouille opened, it was the only table he ever chose to sit at. He would discreetly compose thumbnail sketches, saying, “C’est du théâtre!” For him, for Andy Warhol, and for Truman Capote, there was no other table.

In our “to see and be seen” society, the last part outweighs the first.

Mr. Capote “invited” young journalists to lunch with him at Table 5-Bar. He would arrive early and sit snugly against the wall, nursing his friend Johnny (Walker) or Jack (Daniels) on the rocks. The wall had a function after all: it saved the chronic alcoholic from falling over.

The young journalist would arrive, always on time, starstruck, wide-eyed, giddy to meet the writer, “Tiny Terror,” as he was known. The maître d’hôtel pulls the table out. Mr. Capote pats the settee right beside him, signaling for him to sit. The young journalist does so. They chat. Then he pulls out a pen and notepad, the famished groupie devouring every word uttered by Mr. Capote, feverishly scribbling page after page.

Time for the menus. Barely read, they order. As always, sole grillée for Mr. Capote. A classic! It’s also one of our most expensive dishes. “Make it two,” declares Capote. The young man, under Mr. Capote’s spell, nods obediently.

Mr. Capote’s glass is empty. In earlier years, when he was invited by one of his “swans,” his glass was never dry. Now, after alienating his friends, and maybe to impress upon his young guest that he drinks less, he doesn’t order another one. Instead, he excuses himself to visit “the little boys’ room.”

The waiter pulls the table; Mr. Capote gets up and makes a sharp right. Never mind that he should head left, toward the back, where the restrooms are located. Mr. Capote takes a right instead, exits, and runs down the block to the Berkshire Hotel.

Sole grillée for Mr. Capote. A classic! It’s also one of our most expensive dishes.

Through its numerous transformations, that hotel has always had a bar. Mr. Capote downs a few shots, scurries back a few doors, and slides in at his table. The young journalist may wonder why, during their luncheon, his host gets up frequently, disappears, then reappears, sweating profusely. Maybe he has a weak bladder?, he might think.

For the fourth time during the meal, Mr. Capote gets up. But this time he doesn’t return. Guests go back to their offices, their clubs, their homes, to their lives outside. It’s four o’clock. Lunch is over. The room is empty.

The young journalist asks the maître d’hôtel, “Where’s the restroom, please?” The maître d’hôtel points to the rear. The journalist makes a left and might ask himself, “Why did Mr. Capote make a right, four times?” He walks back there to relieve himself, but also to relieve his curiosity.

Has the literary god fallen from Mount Olympus onto the floor of the loo? He knocks tentatively at the door. No answer. The journalist opens the door. The restroom is vacant.

The journalist returns to the table only to find l’addition. Astonished and embarrassed, he says, “But I’m Truman’s guest.” The maître d’hôtel listens and adjusts the check, out of sympathy. The young journalist painfully understands; he pays what he can. The maître d’hôtel and the staff are familiar with this stunt. Both guest and restaurateur get stiffed comme d’habitude—as usual.

It’s not the first or the last time that Mr. Capote invites paying guests to dine. Notoriety has its privileges.

Charles Masson was the longtime manager of La Grenouille. He is the author and illustrator of The Flowers of La Grenouille