A little over a week ago, Douglas McGrath sent a text to a friend describing his commute from his apartment on the Upper West Side to the DR2 Theatre, off Union Square, where he was performing his one-man Off Broadway show, Everything’s Fine. “Every night when I walk down to East 15th Street to do my show,” he wrote, “I walk down Fifth, looking at the Empire State Building as I go, and then, once I pass it, I make a point of turning back and looking at it from the southern POV. It is always and ever beautiful. Funnily enough, when I come home, I go up Madison and make a point of seeing the Chrysler Building, all lit up. How lucky I am to live here!”

The man was 64. He was no yokel. He had lived in New York for more than 40 years, and his work had connected him with such figures as Carole King, Christopher Plummer, Catherine O’Hara, Nathan Lane, Woody Allen, Gwyneth Paltrow, Daniel Craig, Lena Dunham, Alan Cumming, Sigourney Weaver, and Sandra Bullock. Yet that unjaded “Can you believe this?” buoyancy never left him.

The word “never” may be used definitively, alas, because Doug passed away on Thursday, November 3, suddenly and unexpectedly, of a heart attack. He was a writer, director, performer, journalist, and humorist (and a regular Air Mail contributor).

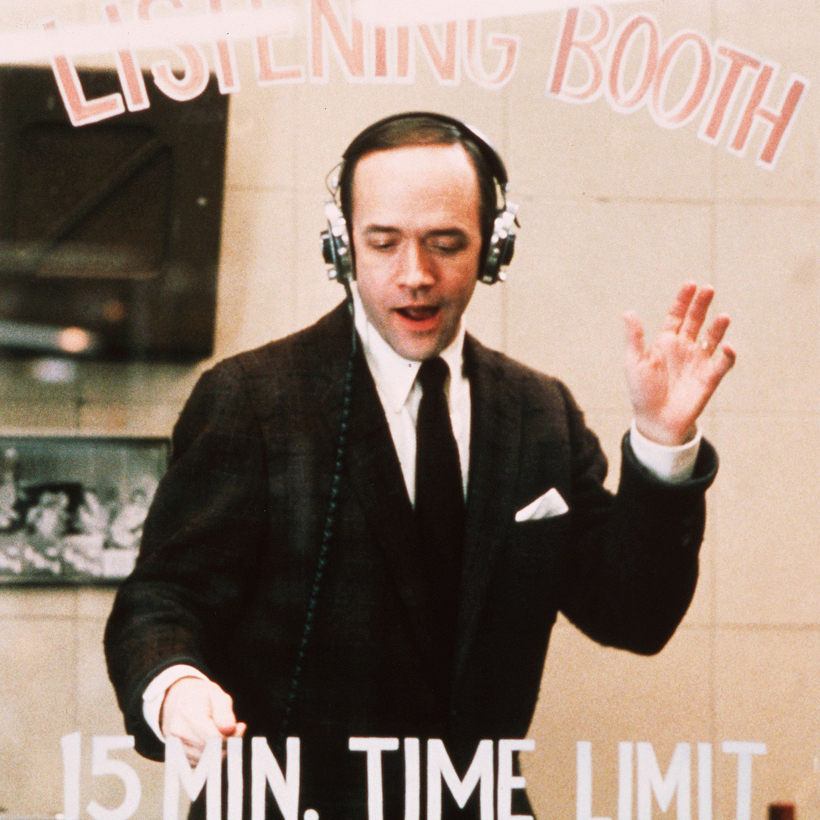

You’re probably familiar with his work, even if his name doesn’t ring a bell. If you happened to catch Beautiful: The Carole King Musical during its five-year run on Broadway, Doug wrote the Tony-nominated book for it. If you remember a cloche-hatted Dianne Wiest huskily cooing “Don’t speak!” to John Cusack in Allen’s Bullets over Broadway, Doug co-wrote the Oscar-nominated screenplay for it. If you recall Dunham’s Hannah Horvath befuddling her tweedy school-principal boss in Girls by flashing her private parts at him, well, that was Doug playing that poor guy.

Doug was a dear friend of mine, and, if I had to hazard a guess, about 12,000 other people’s. Like the late and similarly polymathic Nora Ephron, he was the rare human being capable of instigating and maintaining genuine, heartfelt friendships in basketball-arena numbers. He was urbane in a 1930s, white-telephone-movie way, a slim, gracious man who enjoyed sharing Fred-and-Ginger clips on social media and actually introduced himself to new acquaintances by saying, “How do you do?”

“Doug was such a joyous sophisticate that I just assumed he grew up on Park Avenue with an El Morocco swizzle stick in his hand,” says Air Mail’s own Graydon Carter. “When I first learned of his boyhood in Midland, Texas, I was floored.”

Doug McGrath was urbane in a 1930s, white-telephone-movie way, a slim, gracious man who actually introduced himself to new acquaintances by saying, “How do you do?”

Doug’s origins in that dusty, windy wildcatter town—he likened living there to “growing up inside a blow-dryer full of dirt”—are the subject of Everything’s Fine. Alone onstage in a classroom setting, in a delightful production directed by John Lithgow, Doug recounted a true story of childhood naïveté, in which he recognized, too late, that a 47-year-old female teacher who took a special interest in him in middle school was actually stalking and harassing him.

This tale was told frankly but without self-pity, and with no small amount of levity. That was how Doug rolled—without delusion that this world isn’t a screwed-up place, but with determination to make it as joyful a habitat as possible.

Let me quote from his recipe for his favorite cold-weather cocktail, the old-fashioned, which he circulated every December as Christmas approached. The capitalizations are all his: “HURL 1 tsp. sugar in an Old Fashioned glass, DRENCH in Angostura bitters. Don’t be shy about this—apart from their magical calming qualities, the bitters help give the drink its bewitching color. Take a nice wedge of orange, cut in half, drop it in and MASH IT UP, releasing the pulp from the peel. Add one or two cherries—we love the Luxardos—and SMASH THEM UP, TOO, unless you want to eat them whole at the end, in which case please forgive me for suggesting you smash them up. Stir to mix these flavors into what my beloved friend Liz Tirrell calls ‘a magical tincture.’”

Tirrell tells me that she actually coined the phrase “magical tincture” in reference to a champagne cocktail that she, Doug, and Doug’s wife, Jane, enjoyed at the Paris brasserie La Closerie des Lilas, where they congregated to celebrate the wrap of Doug’s 1996 movie, Emma. (Doug wrote and directed the film, adapting the screenplay from Jane Austen’s novel and giving Paltrow one of her first starring roles.) “The cocktails did something good to us, got us all giggly,” Tirrell says, “so Douglas went to the bartender to get the recipe.”

Tirrell and Doug grew up in Midland as de facto cousins, their parents good friends, their families often spending Thanksgiving together. A few years Doug’s senior, Tirrell, then known as Liz Welch, didn’t grow close to him until she lost her brother, Baker, in a tragic accident in which he was pulled under by a riptide in Florida. “At that point, Douglas stepped into the shoes of my brother. He just assumed that role in my life, and we never looked back,” she says.

That was how Doug rolled—without delusion that this world isn’t a screwed-up place, but with determination to make it as joyful a habitat as possible.

Tirrell moved to New York first, securing a gofer job at a cool new show on NBC called Saturday Night Live. In 1980, by which time Tirrell had ascended to a position as a talent scout for the show and Doug was a senior at Princeton University, she learned that the new, Jean Doumanian–run regime of S.N.L. was looking for new writers.

“I told him to send in some things, but that was the end of my involvement,” she says. “He got hired on his own skills.” That season proved to be the program’s creative and critical nadir—Doug himself said it “helped teach the nation that it wasn’t such a good idea to hurry home from that party and watch the show.” But it launched Doug as a professional creative and, more crucially, introduced him to Jane Martin, a fellow S.N.L. staffer who became the love of his life.

I need not cast about in the recesses of my memory to recover the date that I met Doug: September 11, 2001. That morning, the husband of a mutual friend had gone to a breakfast conference at Windows on the World. By the afternoon, a bunch of us were keeping that friend company in her Greenwich Village apartment, holding vigil and hoping against hope.

Like the late and similarly polymathic Nora Ephron, Doug was the rare human being capable of instigating and maintaining genuine, heartfelt friendships in basketball-arena numbers.

In that grim setting, Doug stood out in his kindness and affability, particularly in the way he engaged with our friend’s kindergarten-aged son. A few weeks later, he pulled off the impossible task of presiding over the husband’s memorial service at First Presbyterian Church—managing, in a dolorous, fearful time of anthrax-filled envelopes and a lingering ash cloud over Lower Manhattan, to make the event feel like a celebration of a life well lived.

How could you not want to befriend someone like that? Our families fused—the adults meeting for dinner (cocktails mandatory), the children for playdates, our son, Henry, going to the summer camp where their son, Henry, did, on their recommendation. Doug, through all the ensuing years, was a reliable source of jollity and a nicely tailored shoulder to lean on. When I belatedly found work in one of his realms, writing for the musical theater, I sent him an S.O.S. text from the West Coast after a disastrous preview. “This is totally normal,” he wrote back. “In fact, it’s why you’re there, to discover these things and fix as many of them as you can. Don’t despair—relax.” He was, needless to say, 100 percent correct.

Doug’s work had connected him with such figures as Carole King, Christopher Plummer, and Catherine O’Hara. Yet that unjaded “Can you believe this?” buoyancy never left him.

This calming, reassuring quality was a key to his success. Carole King is a notoriously private person, in theory an unlikely figure to lend her name and life rights to a Broadway show. “When Doug interviewed me in preparation for writing Beautiful, I was reluctant to have the pain of my young life made public,” she wrote in an e-mail. “But Doug’s gentle encouragement, kindness, and humor were so disarming that I opened up to him. When I finally mustered up the courage to see Beautiful, I realized that Doug’s book had captured the essence of who Gerry Goffin, Barry Mann, Cynthia Weil, and I were in the mid-20th century.”

Another of Doug’s friends, André Bishop, the longtime producing artistic director of Lincoln Center Theater—and the man to whom Doug first sent the script for Everything’s Fine, prompting Bishop to connect him with Lithgow—notes that Doug never got over the fact that he, a kid from Texas, got to play in the same sandbox as the greats he admired. “I had a letter signed by Cole Porter, and I decided to give it to Doug,” he says. “Well, you would have thought that I had given him the sun, the moon, and the stars, he was so excited.”

It’s a tough thing to reckon with: the unwritten McGrath works we’ll never get to see or read, the further fizzy conversations we won’t get to have, the shortchanging of his beloved Jane and Henry, who surely deserved at least 30 more years of his company.

But there’s a measure of solace in knowing that Doug went out at the top of his game—reveling in his show’s good reviews, in the audience’s enthusiastic engagement, in the magnificence of the Manhattan skyline’s Art Deco mainstays.

“His passing brings to mind how, after a show, all the lights are turned off, and a single light bulb on a stand remains to illuminate the stage,” King wrote. “May the light that was Doug McGrath continue to illuminate our lives.”

David Kamp is a Writer at Large for AIR MAIL and the author of Sunny Days: The Children’s Television Revolution That Changed America