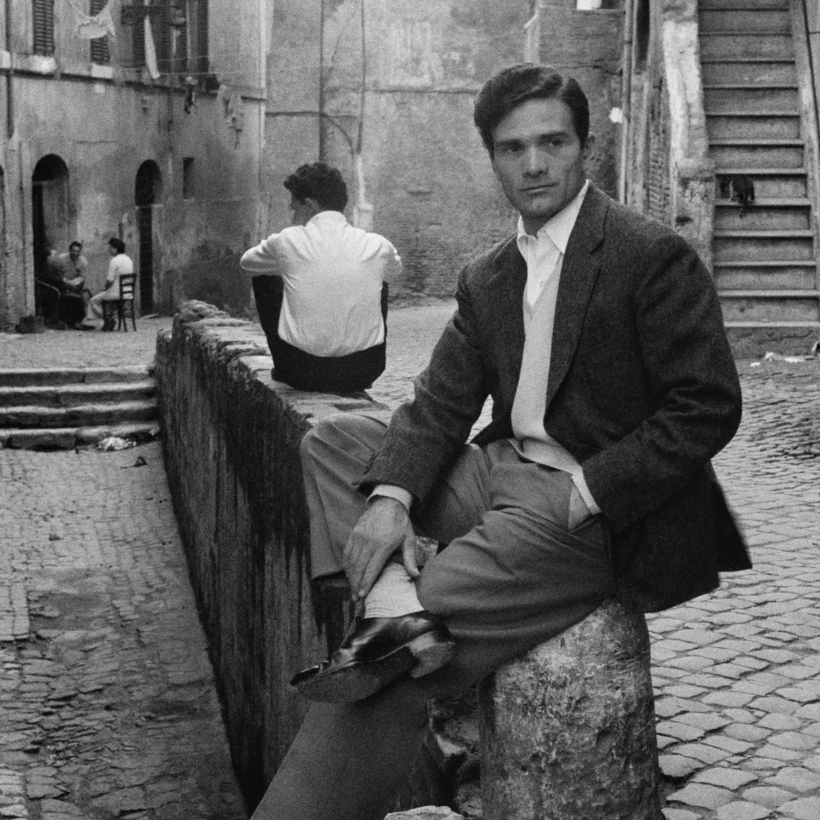

Pier Paolo Pasolini, the writer and director of some of cinema’s most groundbreaking films, was persecuted more than any other Italian intellectual in the history of the republic. Systematically slandered by a radical-right press, he was brought to trial 33 times, accused of obscenity, plagiarism, and robbery. Yes, robbery.

Of all the accusations, this one may have been the most preposterous, or, in any case, the most unexpected. It also became the most frequently exploited by a reactionary 1960s-era Italy, which saw in Pasolini the incarnation of everything it would have liked to eliminate: freedom of thought, freedom to choose one’s own sexuality, and the persistent criticism of power.