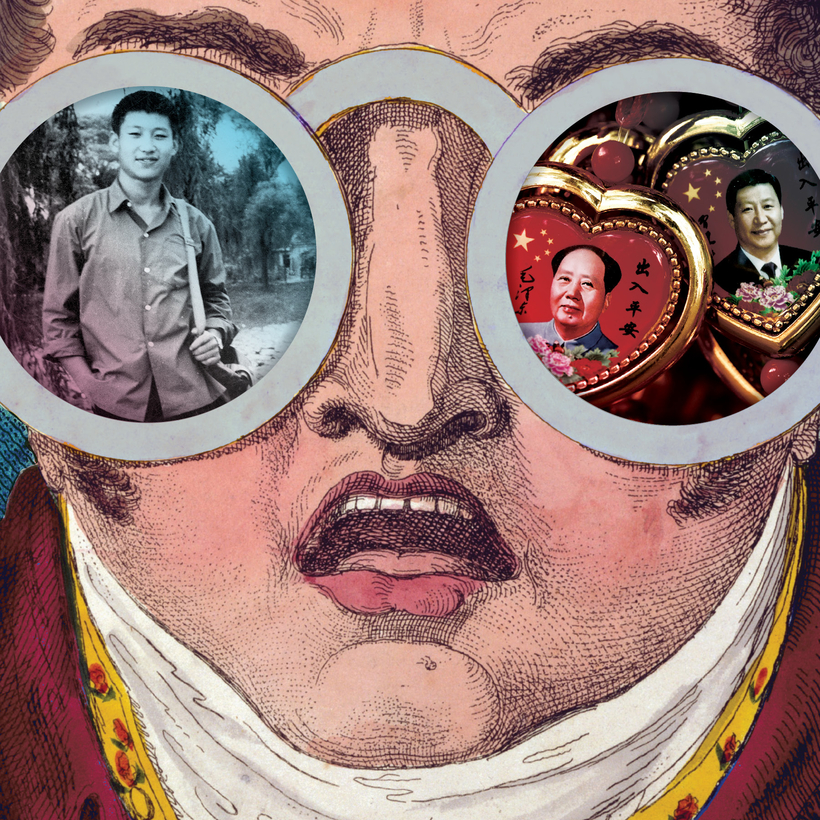

Officially, Xi Jinping does not smoke. He supposedly gave it up in the late 1980s, at his second wife’s urging. But in secret, according to Taiwanese intelligence, which monitors Xi’s health closely, he sneaks outside to light up, away from spouse and cameras. It’s a habit he picked up in the worst period of his life—and which, like the other trappings of his brutalized childhood, he still clings to.

He certainly has not lost faith in the Chinese Communist Party, even now, when the country’s state-run economy is imperiled. Later this month, the party’s Central Committee, the small group of the country’s highest leaders, will once again gather for Xi Jinping to tell them what they’re doing wrong.