Growing up in the 1950s, Denis Sandoz dreamed of escape. He was the youngest of 13 children living at 18 Rue d’Avron, in Paris’s 20th Arrondissement, and was the only family member to receive any formal education. His mother always cried with regret while walking past the local school.

Because he was his mother’s favorite, Sandoz, an inconspicuous boy with brown hair and brown eyes, was allowed to attend public school starting at the age of 12, but his father pulled him out just two years later. From then on, he worked in a mechanic’s shop at Porte de Montreuil with three of his cousins. “I was deprived of the world,” Sandoz, now 80, says in an interview with the authors. “I wanted to see the world, the beautiful world.”

In 1962, when his parents were out shopping, Sandoz took the leap. He spread out a sheet on his bedroom floor and piled it with books, including General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque’s moralist memoir, and clothes. He tied up the corners, slung the bundle over his shoulder, and ran downstairs. Outside, his cousin Gérard was waiting in a taxi, with the meter running.

“Rue Victor Noir in Neuilly, please,” Sandoz said as he got in.

“But that’s the other side of Paris,” the driver complained.

“Yes, yes, I know … it’s far.”

That long taxi ride marked the end of Sandoz’s life in La Famille—a covert religious cult into which he had been born 20 years before.

A Cult is Born

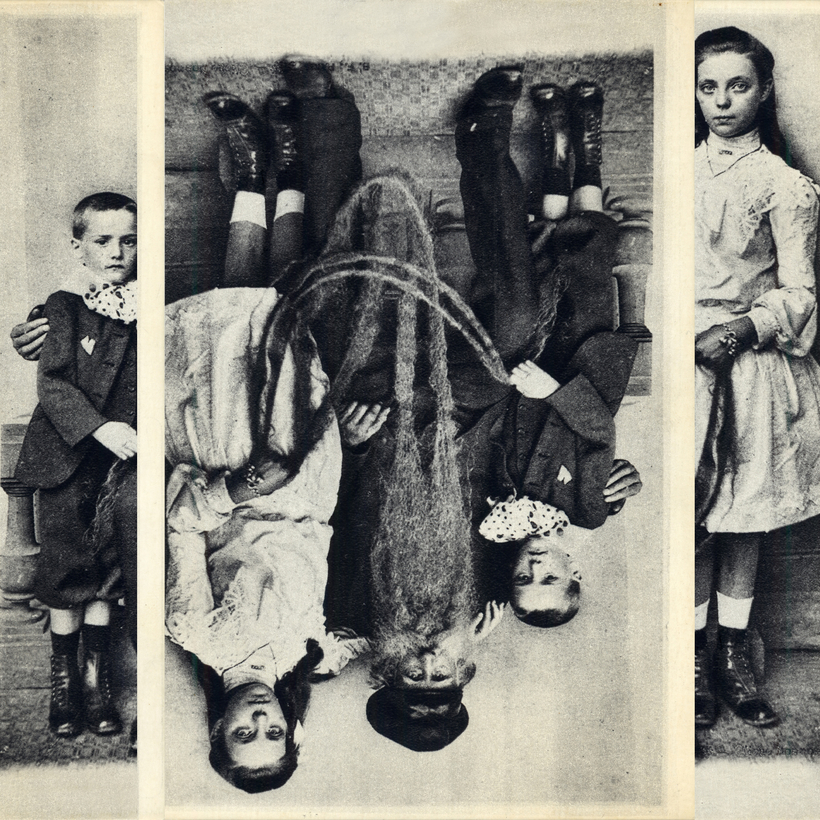

La Famille has existed for over 200 years. Today, experts believe that the insular group has between 3,000 and 4,000 active members, each belonging to one of eight families. The group is closed to new members (or “gentiles,” as they call them), so marriage between cousins is the norm.

According to Dr. Jean-Pierre Chantin, a historian of contemporary religion at the Rhône-Alpes Historical Research Laboratory in Lyon, the roots of La Famille stretch back to the French Revolution and several religious movements of the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries, including Jansenism (a theological movement within Catholicism), the Convulsionnaires (a spin-off religious sect of Jansenism), and the teachings of the dissident priest François Bonjour. Legend has it that it was founded in a Saint-Maur bistro in 1819, when religionists Jean Thibout and François Joseph Havet each placed a coin on a table only to see a third coin mysteriously appear. The miracle linked them together forever.

In 1892, one of the group’s elders and Sandoz’s maternal grandfather, Augustin Thibout, implemented the edicts the group largely still follows today: Men were to work simple, blue-collar jobs, while women should not work, wear makeup, or dress in anything seductive. Schools or any formal education should be avoided as much as possible. And La Famille members were required to live in the east of Paris, where Thibout predicted that the prophet Élie (French for Elijah) would one day return.

Today, La Famille’s members still live alongside other Parisians in the 11th, 12th, and 20th Arrondissements, on the eastern end of the city, and regard themselves as God’s chosen ones. The group has no clear leader and is mostly structured around individual patriarchal family units. While they don’t dress in a particular style, a teacher at an elementary school in Paris’s 20th Arrondissement says she can recognize them. “They’re always extremely well dressed and polite,” she says, adding that their parents are always attentive.

Today, experts believe that the insular group has between 3,000 and 4,000 active members, each belonging to one of eight families.

While some families follow the old orthodoxies to the letter—refusing to travel, home-schooling their children, and requiring that women dress modestly—others take a more relaxed approach.

There is no communal church, so religious ceremonies are held at home. In most cases, the patriarch doubles as the priest and performs baptisms, weddings, and informal ceremonies, as well as having the final word on household decisions.

La Famille shares some characteristics with other fundamentalist communities, such as breakaway Mormon sects, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the 1970s psychiatric cult the Sullivanians. What sets its members apart is their isolation from society, intermarriage, the lack of proselytizing, and the absence of a central leader.

Most former members recall a deep sense of community. “La Famille is very focused on childhood, on the fact that children should be happy,” Valentine, 32, a former member who declined to use her last name, told the French broadcaster BFMTV. “There are an enormous number of things for children.” Mothers frequently organized fun games and outings to the Bois de Vincennes, the vast public park just beyond Paris’s eastern edge.

Today, all children in France between the ages of 3 and 16 must be educated, so it’s unlikely that members would be allowed to deny their children a formal education like Denis Sandoz’s parents did.

One former member we spoke to, Alexandre, in his early 40s, who also asked that his last name be withheld, recalls alcohol playing a major role in life in La Famille, which makes events boisterous. “Everything is done around alcohol, whether it’s ceremonies, parties, religious events, social events, friendships, family, sports.”

Edwige Sandoz, Denis’s niece, who left the group when she was 18, remembers how, if you moved apartments, you never needed to hire help: “A team of 50 people would come to help you move.” She also described communal funds from which money was distributed to members in need.

But while some of Thibout’s rules have loosened over the years, the group’s key tenets remain ironclad: new members are not allowed entry; one must marry within the group; and if you leave, you’re cut off.

Blood Ties

The group’s policy of intermarriage has worried French health officials, due to the heightened risk of genetic diseases. According to a report published in 2021 by MIVILUDES, a French government agency that observes sectarian movements, 30 to 40 members of La Famille are currently suffering from Bloom’s syndrome—a rare condition which is usually caused by consanguinity (having blood ties with your partner)—characterized by short stature, increased susceptibility to infections, and a predisposition to various cancers. The Cleveland Clinic estimates that there are fewer than 300 cases known worldwide. Some experts have expressed doubt about MIVILUDES’s methods, but there is a good deal of evidence that instances of Bloom’s syndrome are much higher among La Famille than among the general population.

Former members also talk of a range of other illnesses including autoimmune diseases, rare pathologies, and cancers. The teacher says children from La Famille in her school often have significant learning difficulties. (La Famille believes that when children are born with disability or disease, it is God’s will. They rarely visit doctors, though this has begun to change.)

Perhaps due to these health concerns, in recent years the French government has begun to pay more attention to La Famille. Since 2015, its members have been the object of 23 MIVILUDES referrals, and the organization published a detailed analysis of the group in 2021.

Yet former members such as Edwige Sandoz say that the government has known about La Famille for decades. In 1977, Edwige attempted to run away from her family and sought help at the Palais de Justice, which contains Paris’s Judicial Center, or courthouse. When they asked for her name, and her parents’ names, she remembers them saying, “Ah, you are part of La Famille.” There was no explanation needed. “We have to stop saying that the social services and the government only learned of their existence in 1990,” she says.

Though there are dangers associated with staying in the group, severing blood ties is difficult. “You have the world and you have La Famille,” Denis Sandoz says. “It is always a great pain to leave.... The members of La Famille play that card: If you leave you will be all alone.”

The group’s key tenets remain ironclad: new members are not allowed entry; one must marry within the group; and if you leave, you’re cut off.

Since leaving La Famille and marrying a man outside the group over 10 years ago, Valentine has not seen her parents, though they exchange messages on holidays. They’ve never met her child. Now 32, she leads a new life. She has traveled abroad, started a family, and is a life coach for adolescents. And though she has her critiques of the group, Valentine still feels a strong loyalty to her immediate family and close friends.

“Even though we’ve chosen different paths in life, I don’t think that in any way detracts from the feelings I have for them,” Valentine says, “and vice versa.”

When you leave La Famille,” Alexandre says, “you lose everything that makes up and has made up your existence.”

Although Denis is Edwige’s uncle, the two have never met. They share similar stories of rebellion, adolescent dreams of liberty, and fleeing in extremis, but when you step out of the community, the guillotine drops.

Eventually, after renting out a cheap room under his cousin’s name, Denis Sandoz went on to work as a butcher in Switzerland, a fisherman in Iceland, and a journalist in Tehran. Edwige Sandoz runs a wellness business in west Paris.

Over the centuries, groups with similar traditions have come and gone. But La Famille is a strong community, with large families, and an urban base where work is plentiful. While he is hesitant to make predictions, Dr. Chantin believes the group will continue to exist, though he says “they may need to re-adapt a little.”

After we contacted dozens of current members of La Famille for this story, only one replied via Facebook Messenger. “You know, for us,” he said, “living happily means living hidden.”

During our interview with Edwige Sandoz, a rumble of thunder—a symbol of God expressing his wrath, according to Thibout’s teachings—interrupted the conversation.

Edwige flinched. “Even now, when I hear a storm,” she says, “I want to hide.”

Makana Eyre is an American journalist based in Paris. He is the author of Sing, Memory and has written for The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Nation, and Foreign Policy

John Knych is an English professor at La Sorbonne, IÉSEG School of Management, and Cergy-Pontoise University. He has worked as a translator, and as a journalist for Agence France-Presse. He’s currently writing a biography of the anthropologist Déborah Lifchitz