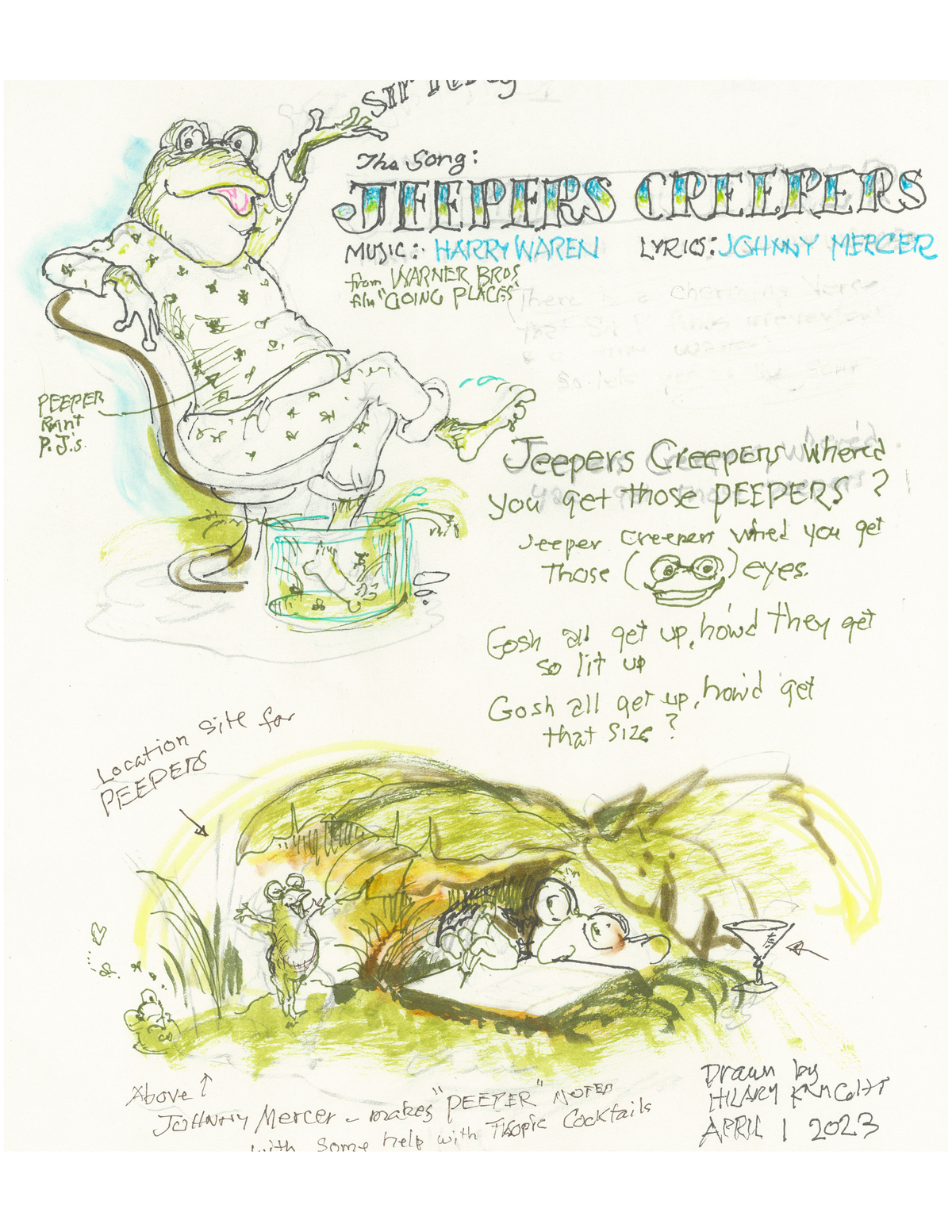

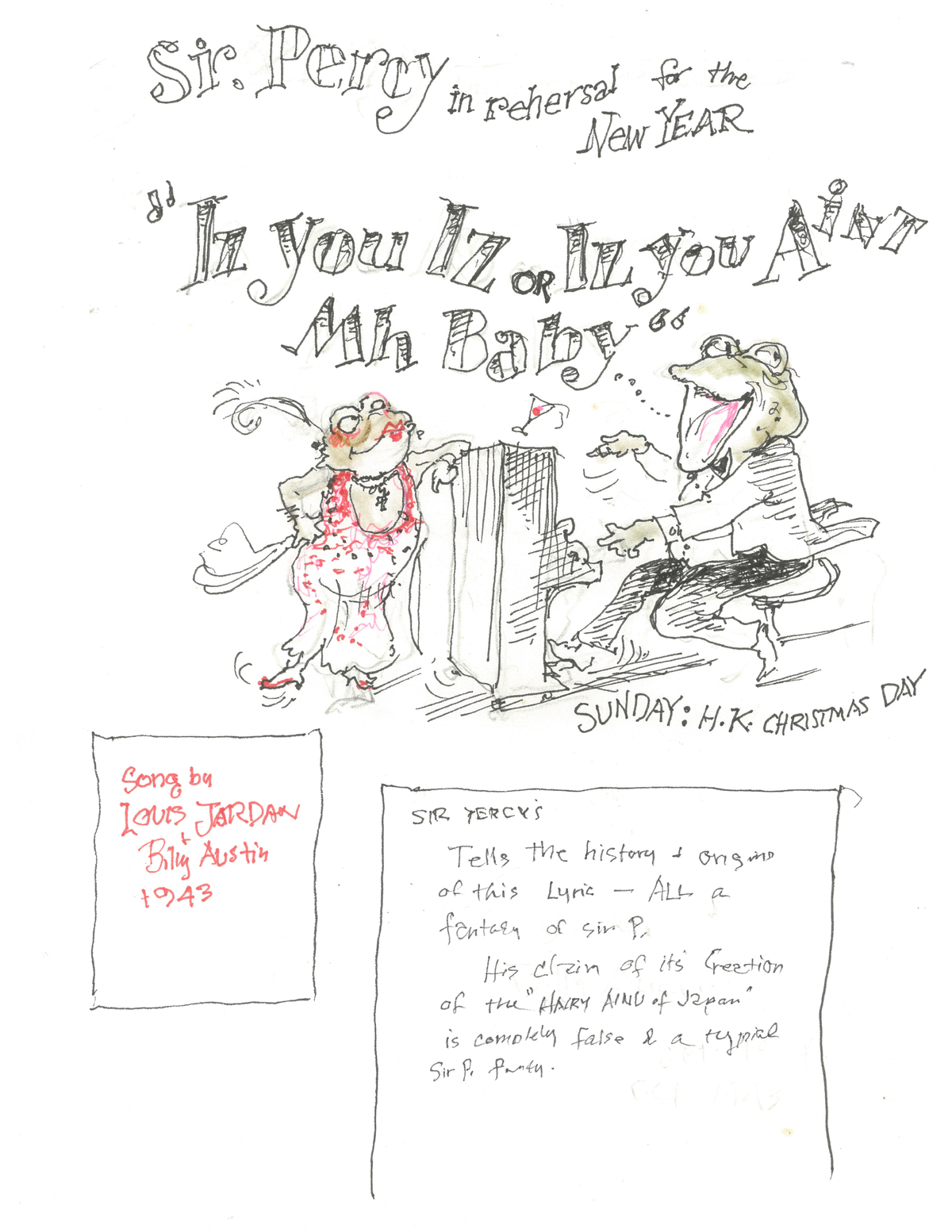

Last spring, several friends of Hilary Knight’s, the near centenarian best known for illustrating Kay Thompson’s Eloise books, received an e-mail with an impressively polished rendering of his newest character, Sir Percy, a smartly dressed frog striking a courtly pose in the manner of Hyacinthe Rigaud’s Louis XIV. Often, artists mature into what art historians call an alter Stil (old-age style), usually characterized by freer brushwork, color, and form. If this freshly minted image was any indication, time had miraculously not altered Hilary’s supple line.

He is “more important & more interesting (to me) than Eloise … & ALL my own invention,” Hilary wrote on April 18 when I asked for more information about his pretentious amphibian. “… remember, Kay was not Child friendly … not in any way!!!! Did that make the book more appealing?? WE have so many things to plan & discuss … it would be absolutely perfect if you could come HERE!!”