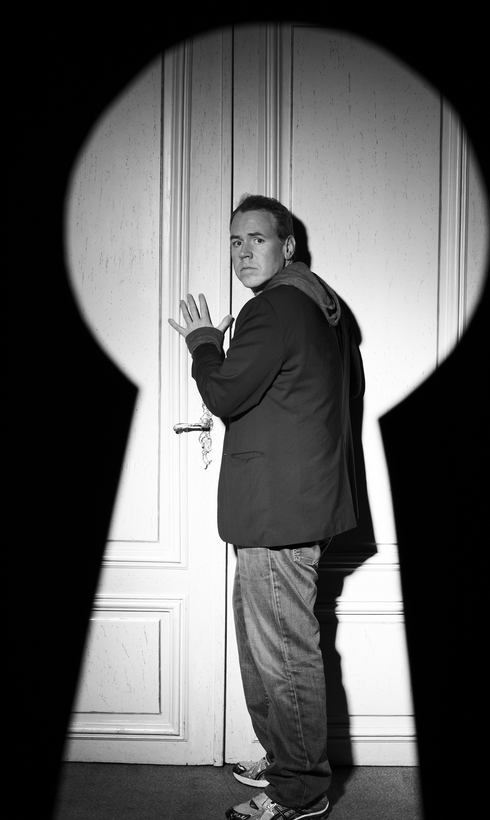

The Shards by Bret Easton Ellis

Even if your parents did love you, in the 1980s, you spent a lot of time as a teenager alone. Also, often, unsupervised—with your friends, in cars, or in empty living rooms in empty midafternoon neighborhoods—but alone, for certain. “Not engaging with your parents for days on end didn’t seem particularly weird or abnormal,” Bret Easton Ellis writes in his new novel, The Shards.

This is the voice of one Bret Ellis, aged 17, a senior in the class of 1982 at the Buckley School in Los Angeles, who is living by himself and working on the manuscript of a novel called Less than Zero, while his parents have gone off to Europe (“trying to repair their flailing marriage,” an effort in whose outcome “I had zero interest”).