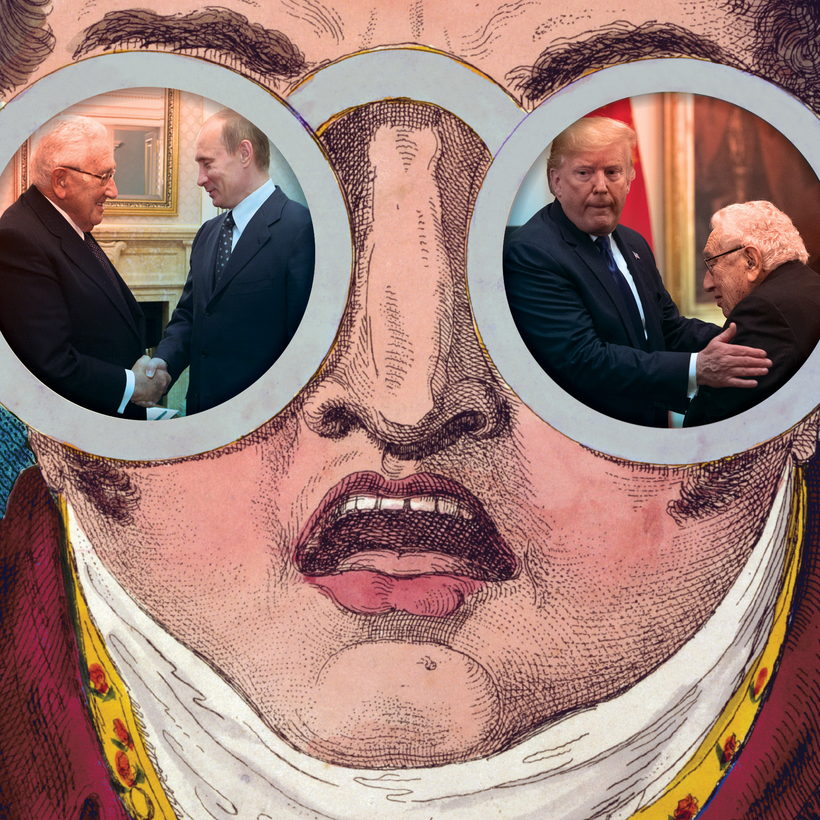

Henry Kissinger has just turned 99, but age has not slowed him one bit in the respect he can muster for an autocrat such as Vladimir Putin. Nothing else can explain why, addressing the World Economic Forum in Davos last month, he advocated that the best road to peace in Ukraine is to officially cede Crimea to Moscow, which it seized in 2014, and give it de facto control of Ukraine’s eastern regions of Luhansk and Donetsk.

None of this sat well with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, who in effect reminded the former secretary of state that this kind of advice from a Jew who lost relatives in the Holocaust to him, a Jew who also lost family members in that horror, was not so much realpolitik as surrealpolitik.