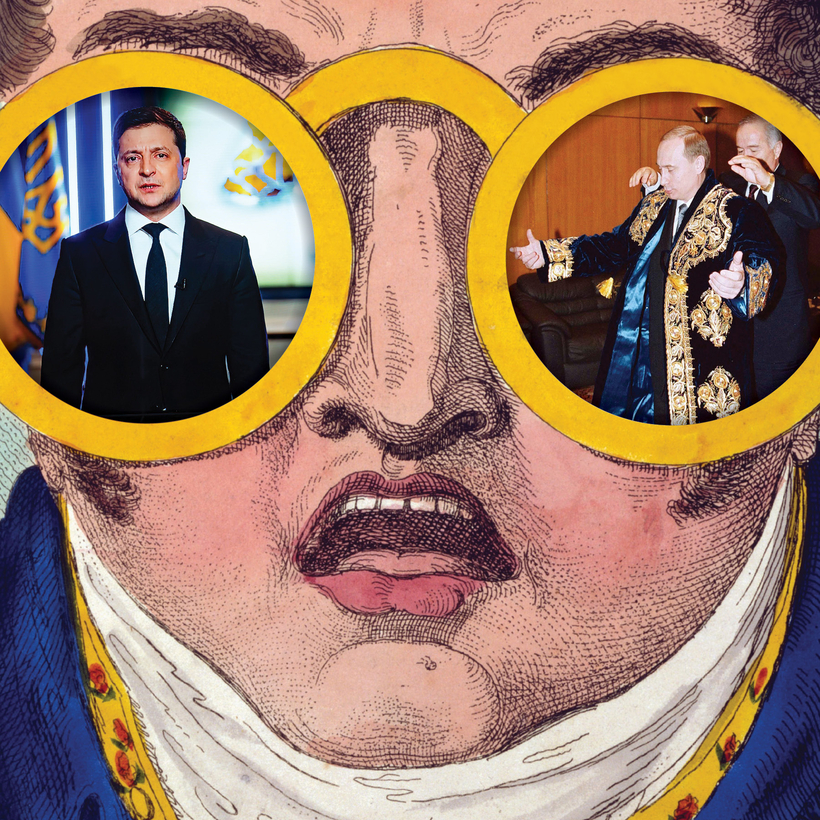

Russian oligarchs are now kleptocrats. Their mansions are mapped, their private jets are tracked on Twitter (@RUOligarchJets), and their super-yachts are on the run. The invasion of Ukraine has finally forced the West to stop serving as the playground and hidey-hole of the Russian elite.

The Justice Department just announced a multilateral task force to “identify, hunt down and freeze” the assets of Putin loyalists. In his State of the Union address, Biden warned, “Tonight, I say to the Russian oligarchs and the corrupt leaders who’ve bilked billions of dollars off this violent regime: no more.”