DUSTIN HOFFMAN (actor): Ovitz.

TOM POLLOCK (executive): Michael Ovitz.

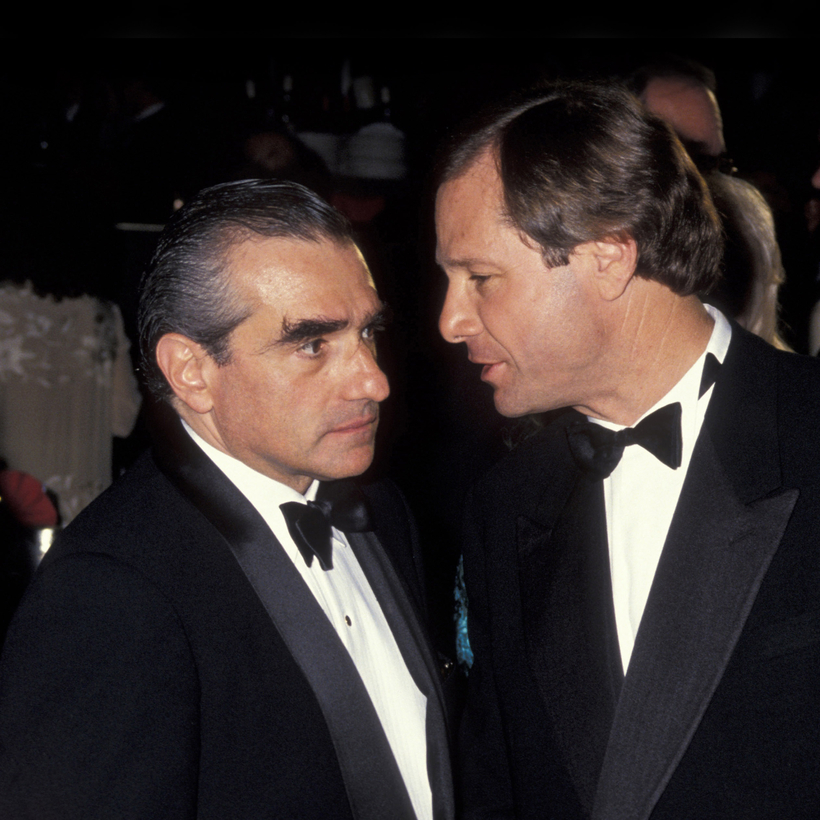

MARTIN SCORSESE (director): Mike Ovitz coming up to me after making The Color of Money and tapping me on the shoulder and saying, “You know, you can get paid for this.”

MICHAEL OVITZ (agent): I grew up in the Valley four blocks from the RKO studio. That’s where I learned. That’s where I became totally enraptured with the business.

I would sneak in. This was the 50s. There was no security. We’d sneak in under the fence and go watch them shoot these black-and-white television shows like Ramar of the Jungle. I can remember watching a group of human beings create an environment that came out of someone’s head, that wasn’t real but became real. And when they said, “Action!,” it was as real as can be. And when they said, “Cut!,” it was just all chaotic. And it was such a mesmerizing experience, because they had people in costume and they had prop masters and they had makeup people and hair people and continuity people, and sitting there as a kid, a 9-, 10-year-old kid, watching this was such a privilege. At the age of 10, I’m watching product being made.

The concept of seeing a group of people all pulling together to get two minutes of usable footage in a 12-hour day—and that’s all they get, two minutes in a 12-hour day. And I would sit and be mesmerized, and no one had to tell anybody what to do. No one said to the makeup person, “Go dab the nose.” No one said to the prop master, “That glass is one foot from where it was, there’s no continuity.” Everyone was an expert in their field. And by the way, I didn’t know what I was knowing then. But I’ll tell you what. I fell in love with it. The process.

I worked for Universal when I was 16. I gave the tours. I was a tour guide. I can’t tell you how much I loved it. There were five guys then, and I was one of them. And I see men walking around the lot in suits, getting treated like God, and then walking up to Lee J. Cobb, Lana Turner, Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Caine, and being well received and hugged. I said, “Who are they?” “Well, they’re agents.” “Where are they from?” When I went into the commissary, it was the agents who were populating it, having lunch with the filmmakers. I witnessed agents doing things the executives wouldn’t do. They took care of every need that the talent had.

I got a job in the William Morris mailroom in 1969. Well, there were two kinds of guys at the agency. There were those that worked their tails off. Like Stan Kamen worked 12, 14 hours a day and then worked at night. But then there were agents like Joe Rifkin, who was a former MGM executive who was there because [William Morris president] Abe Lastfogel owed him. There was another agent there named Benny Thau. Benny did nothing. He just sat and read the newspaper every day. Those guys’ time had passed them by.

It was really weird. They would put TV shows together, but their idea of packaging was not mine. Their idea of packaging was only in television, not in movies. And that’s an important distinction. They would package around a producer. And it became very clear to me that was not the way to do it. The way to do it was to package around the performer, the writer, or director. Period. So I said to the company, “What are we doing here?” Their point of view was I was 26, what did I know?

The other thing I did that no one did was, I read all these books. I read Frank Capra, The Name Above the Title. I read Memo from David O. Selznick. I went to the bookstore. I’ll never forget this. There was a place called Brentano’s bookstore in Beverly Hills. I ordered every book that was a coffee-table picture book, the history of MGM, 20th Century–Fox, Universal, and I studied this stuff like I was going to college. I had a context like no one else.

I’m 21 years old, I’m trying to get ahead [in the Morris office], and there’s no such thing as the Internet, right? Everything’s on paper. And I’m delivering all this paper. And I said to myself, “O.K., what’s the most important thing for me right now? There are two things and two things only: one, to be recognized by senior executives that I’m an up-and-comer, and two, I better learn what they already know.” So I went and bought a woman’s scarf—I’ll never forget this—for, like, 80 bucks at Saks Fifth Avenue, and I brought it to a woman named Mary [a secretary at the Morris office], who had a chain with a key to the file room around her neck. I wanted that key. I brought her the scarf. I was in.

She had a key made for me. So every night and all weekend, I just sat there, starting at 8:00 a.m. I read every deal, every authorization paper, every piece of publicity. I read stuff about Omar Sharif that I shouldn’t have. I read personal correspondence that was filed away. Everything was filed. You weren’t allowed to throw paper out. Everything got filed because you had to keep it for litigation. So I read everything. And I did it in three months.

Those deals were weird. I learned so much. Mostly front-loaded deals, almost no back ends. No one thought [back-end deals] were worth anything. Studios just resisted it. It just took forever. But what I learned by looking at the files was supply and demand.

“I see men walking around the lot in suits, getting treated like God, and then walking up to Lee J. Cobb, Lana Turner, Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Caine, and being well received and hugged. I said, ‘Who are they?’ ‘Well, they’re agents.’”

CAA, in my head, was born in early 1970 in the file room at William Morris Agency. I saw all of it. I saw the future of the business. Didn’t know what to do about it. Didn’t have a clue, because I was on a track at William Morris to get ahead, so I couldn’t put myself in the position of taking myself off that track. But I knew what the company should look like. And that’s why I left.

MICHAEL OVITZ (continued): The Ann Miller thing was the straw that broke the camel’s back. We’re all sitting at the William Morris conference table. And every guy sitting around the table was a senior executive. And then sitting behind them were a bunch of guys sitting in chairs, which were the mid-level guys. And then the rest of us were in the peanut gallery sitting against the wall. And I was the assistant to the president, Sam Weisbord. And Sam announces this amazing news that he’s signed Ann Miller. The reality is that Ron Meyer and I looked at each other and Bill Haber, and we go, “I beg your pardon?” And Ron, to his credit, stands up and says, “Great lady but, like, who cares? Let’s re-sign Steve McQueen. Let’s sign George Roy Hill. Let’s sign serious people.” The company was completely focused on television and Vegas. It was old-school.

This is why CAA killed it. We made a decision in 1978 that I was going to go into the movie business from scratch and build a business. And that’s all I was going to do: movies. William Morris never made that decision. The head of William Morris was the lead television agent. At the end of the day, the man or woman carrying the flag at CAA to this day has to be a motion-picture agent. They have to be. Because it’s still the Rolls-Royce of the business. Long-form celluloid trumps everything else. It just does.

JANE FONDA (actress): I said, “I’m tired of paying all this money to agents that not only don’t get me jobs but don’t give me particularly cogent advice.” There have been some exceptions, of course. But for five years I had no agent. And then I went in and interviewed Ron Meyer and Mike Ovitz at CAA. I felt like I was talking to people who knew how to give me real advice and could make things happen on the studio level. They know what’s going on. They’re very hip politically. They all come in and throw ideas around, and this is what they did with me. Out of one of those kinds of meetings I actually bought two novels to make into movies. No agency ever did that for me before. I never had access to any group of young, exciting heads all getting together to try to service my needs as a company.

MICHAEL OVITZ: What I figured out was that you pull together as a team, that if we’re going to handle Dustin Hoffman, five of us better be working for him, not one. And that was the core of CAA. I said, “We’re going to kill everybody with a simple thesis: if we have a client and he’s only got one agent, there is more likely than not the chance that he will have a conflict with that one agent at some given point in time. But if he’s got five agents working for him, he can move past one to pick up the other.”

SAM WASSON (film historian): As large agencies grew their client lists, they grew in power. After all, they were selling what the studios were buying. But what then was a studio?

A Hole in the System

MICHAEL OVITZ: Heaven’s Gate. Believe it or not, that was all very helpful to me. This is how it happened …

SAM ARKOFF (producer): Mr. Cimino won an Academy Award. I’m not going to talk about how good a picture he made, The Deer Hunter. O.K., it was a pretty good picture, all things considered. All of a sudden he’s out making Heaven’s Gate, what is nothing more, really, than a Western.

ISTVÁN POÓR (director): When you finished the script of Heaven’s Gate, what was the first reaction of the studio?

MICHAEL CIMINO (director): Well, they never saw a script. I presented it. I just talked it through. It took me two hours. It was an oral presentation, which is kind of difficult to do. I sat in a room with half a dozen people and told them the story. And they committed to making it based on that presentation.

SAM ARKOFF: Now, Westerns have not been particularly successful in recent years. The old Western legend is really gone. Kids don’t grow up with guns as much today as they do with spaceships. But the fact still remains that with a budget of somewhere in the neighborhood of $10 or $12 million, Mr. Cimino is now over $30 million. Now, you know, this is utter nonsense. I don’t care what you think about the creative rights and so on and so forth. That’s absolute nonsense.... I don’t think anybody will question Michelangelo was a great artist, but when the Pope hired him to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the Pope told him what he was going to pay him. And he didn’t tell him to cover all the walls and the floor and this and that. He told him, “Paint the ceiling.”

MICHAEL CIMINO: We began preparing the film before we ever had the script. I mean, the physical preparation.

MARTIN SCORSESE: Well, it all comes down to power at some point. How much muscle do you have, and what will they put up with?

MICHAEL CIMINO: It was just a tremendous physical job. And just the sheer size of it. I mean, just to deal with 80 teams of horses. The amount of wranglers that one needs for that.

MARTIN SCORSESE: Obviously I’m going to try to get for myself as much freedom to do what I want to do as the situation will bear.

JOHN LANDIS (director): Hollywood’s become so fragmented, the superstructure is broken down in terms of the studios. So what happens is, once a director is hired, he is basically the producer of the movie.

GARETH WIGAN (producer): I think the producer is being squeezed out, not only by the studio wanting to take charge but, in a funny way, also by the studio abdicating some of the take-charge things—say, “We want this star, we want this director, so we will give them the power.”

A. D. MURPHY (critic): Say that the director wants the big scene. The studio says, “Oh, well, what the hell, let him do it.” It’s going to come out of their participation anyway. There is nobody there to say, “Wait a minute.” But a good producer would be there to say, “Wait a minute.”

MICHAEL CIMINO: The movie opens with a commencement scene. Now, there are 800 people in that scene. Now, they all have to be dressed. All of those people had to be cast. In other words, nobody was just put in. Every person who was there was Polaroided. There was a Polaroid taken of every person. Each face was selected. Those people were then dressed. I then reviewed those people, and we made adjustments in each of their wardrobe, change hats, change coats, whatever. Everybody was altered, you know, if trousers didn’t fit right, if shirts didn’t fit right. Now, another Polaroid was then taken, so that you wind up with 800 Polaroids all precisely numbered.

“With a budget of somewhere in the neighborhood of $10 or $12 million, Mr. Cimino is now over $30 million. Now, you know, this is utter nonsense.... When the Pope hired [Michelangelo] to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the Pope told him what he was going to pay him.”

LAURA ZISKIN (producer): You hire the directors. My friend Bob Garland says it’s the only business in the world where you hire someone who becomes your boss.

FRANK MARSHALL (producer): The final decision is the director’s in every area and doesn’t stop with directing actors. You got to direct the wardrobe guy, you got to direct the propman, you got to direct the transportation guy, you got to direct the marketing people. It never ends.

MICHAEL CIMINO: Now, also, we have a street. There are a thousand people on a street, and you’ve got 80 teams of horses and a train. You’re dressing certain people that you know you want a certain look at the railroad station, a certain look of people on the streets. Nobody will see it, but there’s a group of masons walking down a street. And so you begin, simply, “O.K., take this face here and this face.” And then you begin composing the street. And we took one full day to arrange it. You can’t have several thousand people wandering around not knowing where they go.

GEORGE LUCAS (director): There’s an individual called the line producer. And he is the one I would call the real producer. Some people wouldn’t say that, but I would say that. He’s the guy that manages the movie. He’s the guy that is the business manager for movies. Basically, he hires people, he fires the people, he scheduled the movie he needs to have done on time. He’s the real nuts-and-bolts guy. He’s the guy that sees to it the checks are cut and people get paid and, as they got hired in the field, comes in on budget. And he’s there to help the director achieve his vision economically and resourcefully and creatively. It’s a very creative job. It’s just creative in a very different way.

MICHAEL MANN (director): It’s like being a janitor for a high-rise.

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: What a silly art form, what a wonderfully silly art form to give you a budget, based on something they know nothing about. We got a scene here to do, and they’re telling you it’s got one lighting setup, three actors on a stage, a reverse shot with the crowd out there, it should take you no more than a half a day or a day. What happens if we don’t cook? What happens if something’s wrong and we’re not getting it? Can we stay here another day?

MICHAEL OVITZ: The incredible failure of Heaven’s Gate left a hole in the system. It left the studios gun-shy. So what we at CAA did was step in. It was the best thing in the world for us. I woke up one day, and I said, “My God, this is a godsend.”

Life in the movie business started to change. What began to happen is that 1 movie out of 10 pops—Superman in 1978—but only one. And then nine little ones behind it, Raiders of the Lost Ark and then everything behind it. So each year the split between the big movies and the little movies narrows. It goes from one and nine to two and eight, four and six, five and five, and then, when you get into the mid-80s, everything goes big again and all the 70s stuff dissipates.

A Step Ahead

MARTIN SCORSESE: By the time we finished Raging Bull and it was released, the whole industry had changed.

TOM POLLOCK: Basically what’s happened is that the studios abdicate the creative initiative for a film to outside talent, whether it is an independent producer with an idea, a director with an idea, or a writer who with his agent comes in and says, “I’d like to develop this idea.”

SUE MENGERS (agent): Agents have more power than the studios. They need the agents, because the agents at the moment are the major suppliers of talent and material.

MICHAEL OVITZ: The studios were just banks.

GORDON STULBERG (executive): The more you can package outside the studio, the better the chance you have of having it considered at the top level of the studio and getting a fast answer, yea or nay, a fast answer.

JOHN PTAK (producer): I mean, the most common package is really a writer-producer or a writer-director.

JULIA PHILLIPS (producer): I think that’s why there are so many bad movies: too many good packages.

MICHAEL OVITZ: CAA packaged 300 films in 15 years. Everything we did was a package. The economy was so flush that if you pitched me an idea, I knew if I could get financing or not. So I could say to the writer or director, “It’s a go.” And the writer would look at me and say, “What do you mean, it’s a go?” And I’d say, “We’re going to get it paid for.” That’s what I would say. And I was never wrong. Neither were the other agents in the building, because (a) we were culturally attuned, (b) we knew what the schedules were of each company, (c) we basically programmed two of the six studios, Christmas and summer movies. There wasn’t a year in 10 years that Columbia didn’t have a CAA package.

MERYL STREEP (actress): [Sam Cohn at ICM] wasn’t interested in me doing Sophie’s Choice because he didn’t handle [Alan] Pakula or [William] Styron.

SAM ARKOFF: Now, agents don’t know anything about making pictures. All they know is the fact they learn their craft, or what they know about the business, by representing clients. Now, they don’t know anything about production itself. So the problem is, they want to be nice guys. Agents always want to be nice guys. And that’s no time for a nice guy. Not, after all, as long as this is a business, which has, as one of its purposes, at least making enough money so that you can continue to do business next year.

“The studios were just banks.”

MICHAEL OVITZ: Tootsie was a passion project of Dustin Hoffman’s, and it was our goal to package the elements around him. Bill [Murray] was my client and my friend, and so was Dusty [Hoffman], so was Sydney [Pollack]. I had to get all of them to agree to work with each other as a package. We did.

Dustin cast the love interest for Tootsie in our office. Two hundred women came in to read for both parts [Jessica Lange’s and Teri Garr’s]. Now, I will say selfishly, I didn’t talk Dustin out of casting at CAA for another reason: it made CAA look like we were omnipotent. A giant movie is casting out of the CAA building? And the agents of these women are sending their clients to CAA for an assignment? I knew exactly what I was doing.

We were always a step ahead. The staff meetings at our competition started at 9:30. I started ours at eight. We finished at 9:30 with all that information. Like if you came to the table, you’re an agent, and you said, “There is this book. I’ve read it over the weekend. It’s phenomenal, and it’s great for Gene Hackman.” “Great. We don’t represent Gene Hackman.” “Not a problem. Let’s call him.” Nine thirty, get out of the meeting. One of the agents calls Gene Hackman, says, “We’re sending you this book. It’s perfect for you.” His agent gets out of their meeting at 11. Gene Hackman’s already put a call in to him. CAA’s already given him a book that he read that he’s interested in. We’re always a step ahead. We’re just always a step ahead.

We put together big movies. We packaged them around talent. That’s what we did.

ROBERT EVANS (executive): Blockbusters …

JANE FONDA: Whatever happened to trying to deal with the broader community?

A. D. MURPHY: The attitude right now is “Enough, enough, I’ve had enough.” Some of the films in the 60s, and the plays and the books, were antagonizing the very people that they were trying to reach. And as soon as Vietnam ended, I think in this country and a lot of countries, people said, “Enough. We’re going to stop right here and kind of let everything settle down before we move along.”

DAVID ANSEN (critic): I went back, and I looked at what the summer movies were in the summer of ’71. And it was a whole different world. I mean, you got movies like McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Panic in Needle Park, which nobody, nobody would think of as a summer movie. And even the sort of more popular things like Billy Jack had a definite sort of counterculture edge. Because one of the things that happened was the counterculture sort of ceased to exist and there was just one culture.

ALJEAN HARMETZ (film historian): What was very interesting about the movies of the 70s was that movies that were essentially downbeat, movies that didn’t have happy endings, movies that were ambiguous had a mass audience. People were willing to accept that. And that lasted through ’77.

MICHAEL OVITZ: 1980.

MARTIN SCORSESE: I think things changed from 1981 on.

CHARLES CHAMPLIN (critic): For a time, when the movies had this new freedom, they began to get into hard-edged things and social realism, exploiting the new freedom of the screen in a positive way rather than a negative way. But as Vietnam wore on, as the economy continued to fall apart, there was this continual erosion of confidence in the processes of government. I think people found it harder and harder to go out and experience yet more psychic pain in the movie theaters, this despondent view of the human condition.

SAM ARKOFF: And once it was over, there wasn’t very much left of it, except a few gold beads on middle-aged men. But while it lasted, it was one hell of a decade.

JULIA PHILLIPS: Now every studio has a very big, very expensive picture, and if some of them happen to be science fiction, it would be because of the special effects. It’s getting very expensive to make a movie.

NIRA BARAB (actress): Is that going to change?

JULIA PHILLIPS: How is it going to change? How is it going to go back?

NIRA BARAB: I don’t know. Isn’t something—

JULIA PHILLIPS: Well, when it all goes into the toilet and some other person comes along with something that’s like an Easy Rider that was made for no money independently, then everybody who’s 22 with a light meter around his neck is going to be a director again.

Jeanine Basinger is the Corwin-Fuller Professor of Film Studies at Wesleyan University and the author of several books, including I Do and I Don’t: A History of Marriage in the Movies

Sam Wasson is the author of several books, including The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood and Improv Nation: How We Made a Great American Art