One hundred years ago this past October, T. S. Eliot’s long poem “The Waste Land” was published in the debut issue of The Criterion, the literary magazine he edited in London. James Joyce’s novel Ulysses had appeared a few months earlier, and, ever since, 1922 has been remembered as the annus mirabilis of literary modernism.

“Modern” is a relative term, and after a century most avant-garde artworks have been thoroughly tamed. The French Impressionist painters were seen as wild radicals in the 1870s, and what could be more innocuously pretty today than a Monet landscape? But somehow “The Waste Land” is different. Readers encountering it for the first time still find that this poem demands a different kind of reading than they are used to. It asks us to set aside the questions we usually ask about a piece of writing—whose voice we’re listening to, what exactly it means—and attend instead to the emotional power of its rhythms and images.

A 34-year-old American who had lived in England since 1914, Eliot saw London as a city haunted by war and coarsened by modern culture and technology. In “The Waste Land,” people walking to work in the morning appear as damned souls in hell: “Under the brown fog of a winter dawn, / A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, / I had not thought death had undone so many.” A man listens dully as his wife has a nervous breakdown: “‘My nerves are bad tonight. Yes, bad. Stay with me. / ‘Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.’” A woman in a pub worries that a self-administered abortion has ruined her health: “The chemist said it would be all right, but I’ve never been the same.”

The poem’s style was as challenging as its subject matter. James Joyce and Virginia Woolf introduced readers to the idea that a novel could reflect the “stream of consciousness,” the succession of stray thoughts that pass through our minds. But “The Waste Land” doesn’t seem to inhabit any single mind, not even the poet’s. “These fragments I have shored against my ruins,” Eliot writes near the end, and the poem’s 433 lines are a succession of broken scenes and interrupted voices, with no apparent connection or master plan. Pub conversation gives way to majestically formal verse; obscure literary allusions mingle with lyrics from popular songs (“O O O O that Shakespeherian Rag— / It’s so elegant / So intelligent”). There are lines in German, French, Italian, Sanskrit.

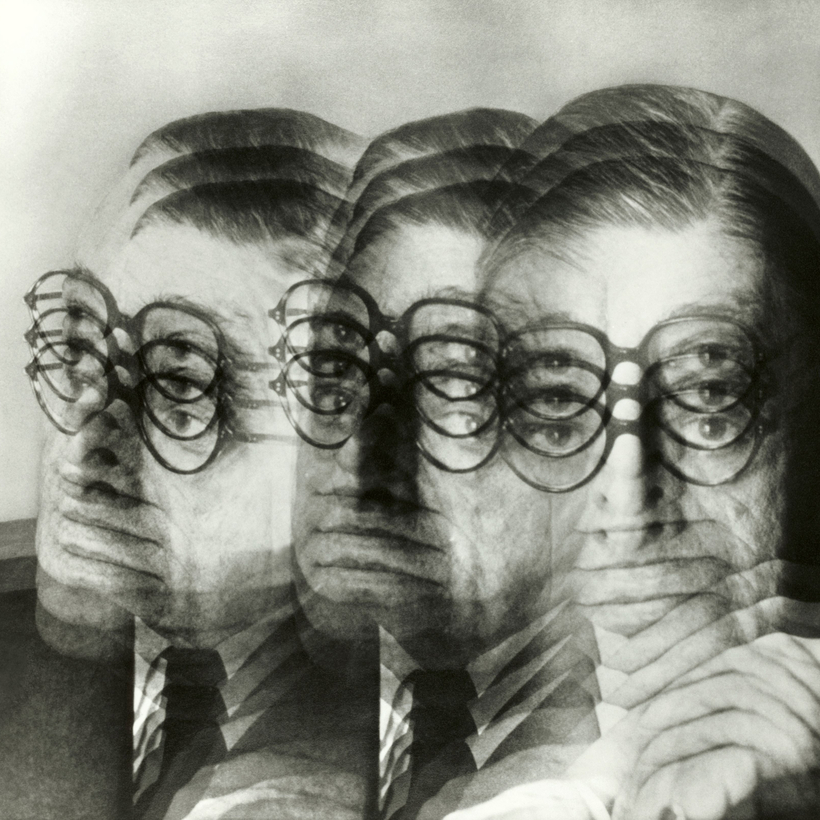

Contemporary reviews of “The Waste Land” show that even sympathetic readers didn’t know what to make of it. “Most poems of any significance leave one definite impression on the mind,” wrote the English poet Harold Monro. “This poem makes a variety of impressions, many of them so contradictory that a large majority of minds will never be able to reconcile them.” Unsympathetic readers had the feeling that they were being left out of an inside joke. “To us who cannot read with Mr. Eliot’s spectacles, colored as they are by Mr. Eliot’s experience, it must remain a hodgepodge of grandeur and jargon,” wrote one American critic.

“The Waste Land” doesn’t seem to inhabit any single mind, not even the poet’s.

When “The Waste Land” was published in book form at the end of 1922, Eliot added footnotes to explain some of his references. This display of erudition only confirmed the poem’s intimidating reputation, which Eliot regretted, saying he had only included the notes because the poem by itself was too short to fill a book. Later in life, he reacted against the thicket of academic interpretation that had grown up around “The Waste Land” by describing the poem as simply “a piece of rhythmical grumbling.”

There’s more to it than that, of course, but Eliot wanted to remind readers the poem was not written as a puzzle to decode. Like all poems, it was an act of expression, a way of giving shape to the poet’s own feelings and perceptions. Traditional lyric poems do this more straightforwardly. More than a century before Eliot, William Wordsworth made his anxious mood perfectly clear in “Resolution and Independence”: “We Poets in our youth begin in gladness; / But thereof come in the end despondency and madness.”

Eliot, by contrast, doesn’t say how he feels or what he’s thinking about. Instead, he makes us wonder what kind of a mind would feel compelled to invent the things we hear and see in “The Waste Land.” By the time his masterpiece appeared, Eliot was already well known as a literary critic, and he invented a name for this kind of indirect expression in one of his best-known essays, “Hamlet and His Problems”: “The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an ‘objective correlative’; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion.” Working with objective correlatives, the poet doesn’t have to say, “I feel”; instead, he writes something that will produce the same feeling in the reader.

When we read in “The Waste Land,” then, about sordid city streets and parched landscapes waiting for rain, we aren’t watching a movie of the way London really looked in 1922. Rather, we’re seeing Eliot’s objective correlatives of his own spiritual state. Read in this way, it’s not surprising to learn that, a few years after “The Waste Land,” the poet was baptized in the Church of England and became a devout, lifelong Christian. Reading about it in “The Waste Land” is challenging enough; imagine how urgently you’d want to escape if you lived there.

Adam Kirsch is the author of The Blessing and the Curse: The Jewish People and Their Books in the Twentieth Century and an editor for The Wall Street Journal’s weekend Review section