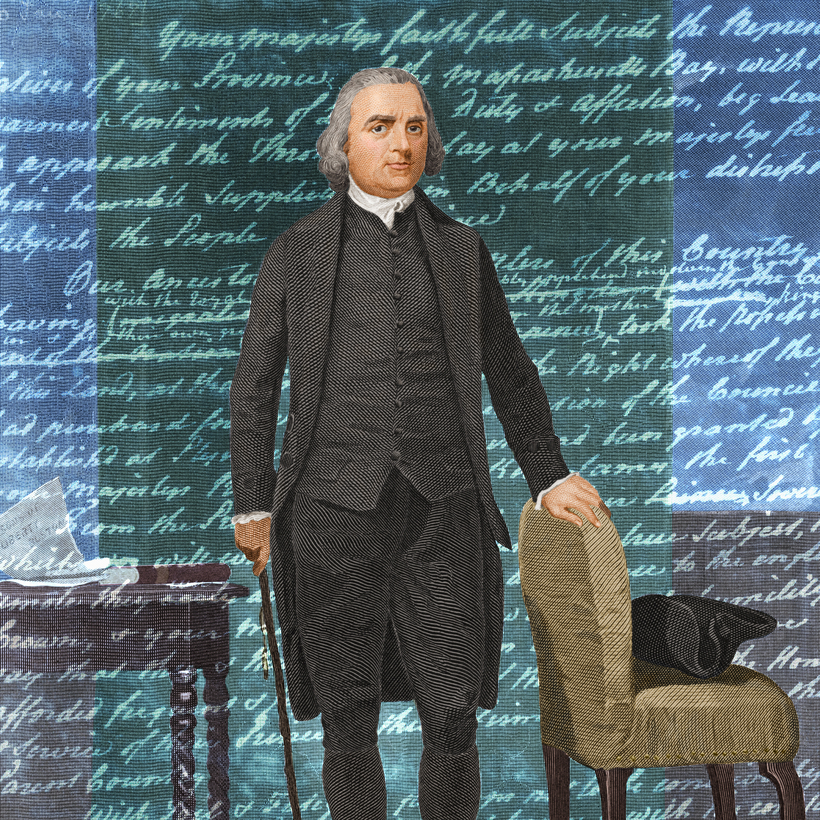

Stacy Schiff is one of our finest biographers, able to explore and illuminate lives as diverse as those of Cleopatra and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, author of The Little Prince. Véra (Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov) won the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for biography. Her latest subject is Sam Adams, second cousin to John Adams and the least well chronicled of our Founding Fathers. That was partly by his design, and partly because the young country chose to forget him. Now, as it turns out, he is best known as the name on one of the country’s most popular craft beers, but after reading Schiff’s book The Revolutionary, you will wonder why his face is not also on one of the bills we use to buy that beer.

JIM KELLY: Your new book, about Samuel Adams, is an exhilarating read, bringing to life a man often overshadowed by other Founding Fathers such as Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin. Here is the man who helped engineer the Boston Tea Party, the man whom Jefferson himself called “the earliest, most active, and persevering man of the Revolution,” the man so wanted by the enemy that when Paul Revere rode to Lexington in 1775, he was doing so to warn Adams that the British were coming. And yet he has been largely unsung. Why is that?