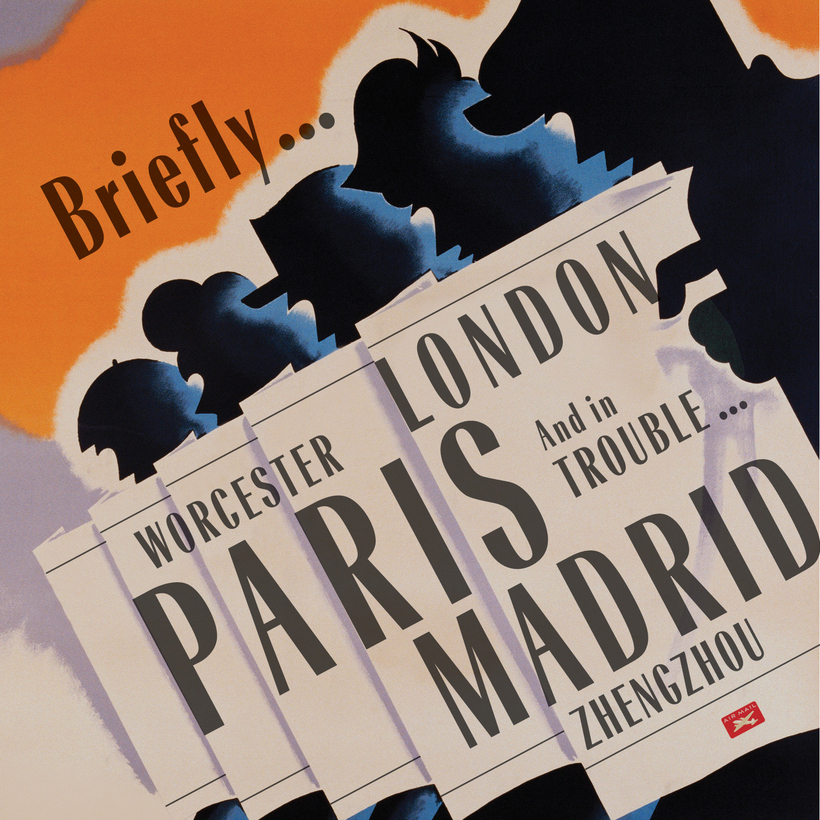

In Zhengzhou …

Can I get that to go?

A 30-year-old woman was stranded on a blind date for at least four days when this Chinese city recently went into sudden lockdown. Her date had invited her to his apartment for dinner—he was proud of his cooking—but as the meal ended, the enforced quarantine began. The woman, identified only by the surname Wang, took to social media to describe the “not ideal” situation. “She also posted short videos documenting her daily life in lockdown,” reported The Guardian, videos that show her date “cooking meals for her, doing household chores, and working on his laptop while she sleeps, according to clips published by local Chinese media.”

It’s not clear how long Wang remained at the man’s apartment—or, indeed, whether she’s still there. While “he’s as mute as a wooden mannequin, everything else [about him] is pretty good,” Wang told a Shanghai news outlet last week. “Despite his food being mediocre, he’s still willing to cook, which I think is great.”