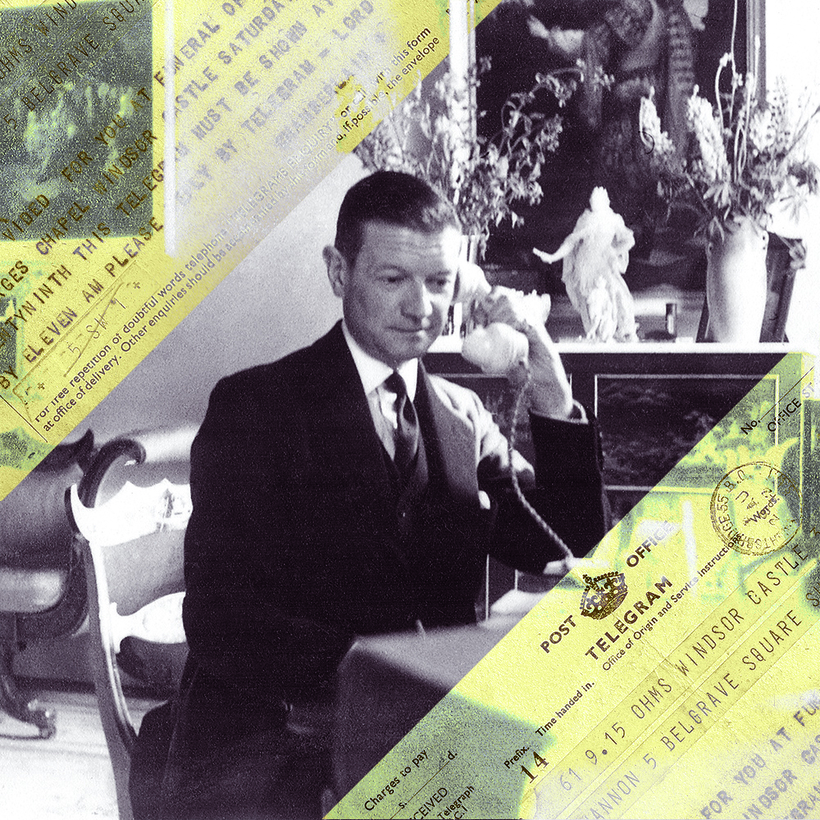

When the diaries of Field Marshal Earl Haig were published in the 1930s, he was unkindly described as one of the few men in history to have committed suicide after his death. Much the same might now be said of Henry “Chips” Channon, the Chicago-born millionaire, socialite, bisexual, antisemite and feather-brained snob who sat as Tory MP for Southend from 1935 until his death in 1958.

The first version of his diaries, which appeared in 1967, represented only a fraction of the material he had left behind, and which he always hoped to have published. It immediately took its place alongside the journals of Harold Nicolson as one of the most engrossing accounts of English high society and politics in the 1930s and 1940s. Even so there was an unpleasant undertone. “You can’t think how vile & spiteful and silly it is,” wrote Nancy Mitford in the 1960s. “One always thought Chips was rather a dear, but he was black inside how sinister!”