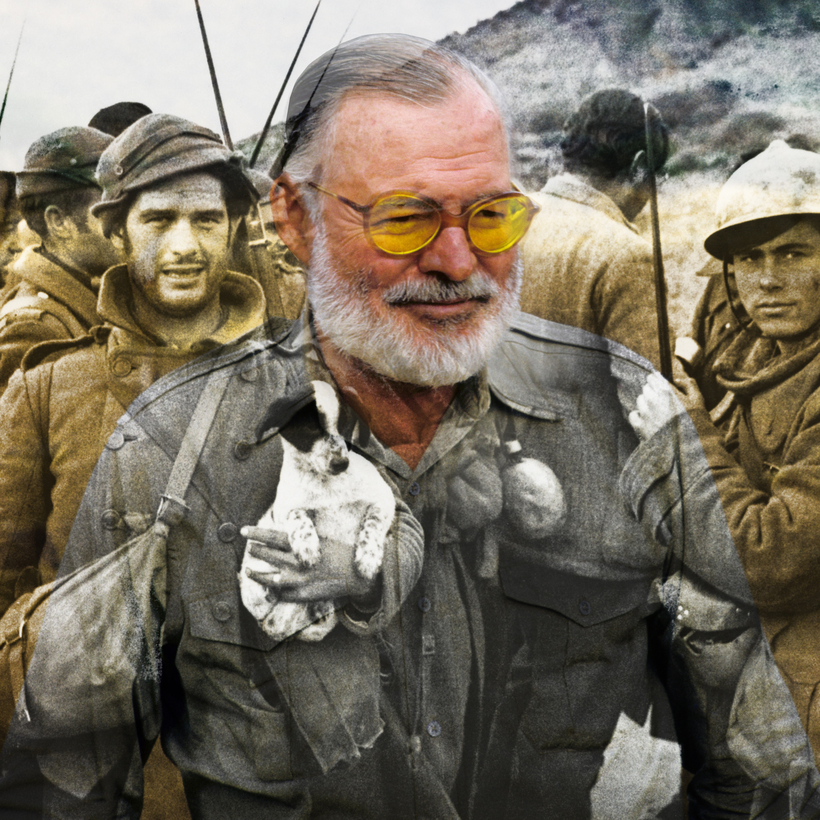

Ever since he had first visited the Pamplona bull runs, Ernest Hemingway was fascinated by Spain—it informed his best work, including The Sun Also Rises and For Whom the Bell Tolls.

The latter is set during the Spanish Civil War, in the late 1930s, with the volunteer fighter Robert Jordan as its protagonist. Jordan gives up his life for a cause close to Hemingway’s heart: that of the Democratic Spanish Republic, whose elected government finally lost a three-year war on April 1, 1939, to Fascist-backed rebels led by soon-to-be dictator Francisco Franco.