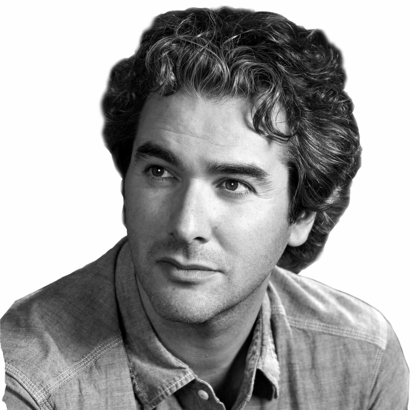

In 2008, Peter Bellerby decided to buy his father a globe as an 80th-birthday present. The options, he found, were unsatisfactory. The majority were plastic, poorly made, and intended for schoolrooms. The rest were priceless antiques. So, despite having no artisanal background—he had previously worked in property development—Bellerby decided to build one himself. Two years later, through much trial and error, he had turned a birthday present into a business. Bellerby & Co. Globemakers has been remaking the world ever since.

Working out of a well-lit warehouse in North London, Bellerby, 55, has a team of 25 that includes fabricators, painters, woodworkers, and cartographers. It takes between six months and a year for him to train each person in the craft of globe-making. Last year they made some 600 globes, from 8.5-inch desk globes (starting at around $1,520) to the 50-inch, 6.5-foot-high “Churchill” globe (starting at around $90,280), inspired by the matching globes George Marshall gave the prime minister and Franklin Roosevelt for Christmas in 1942.