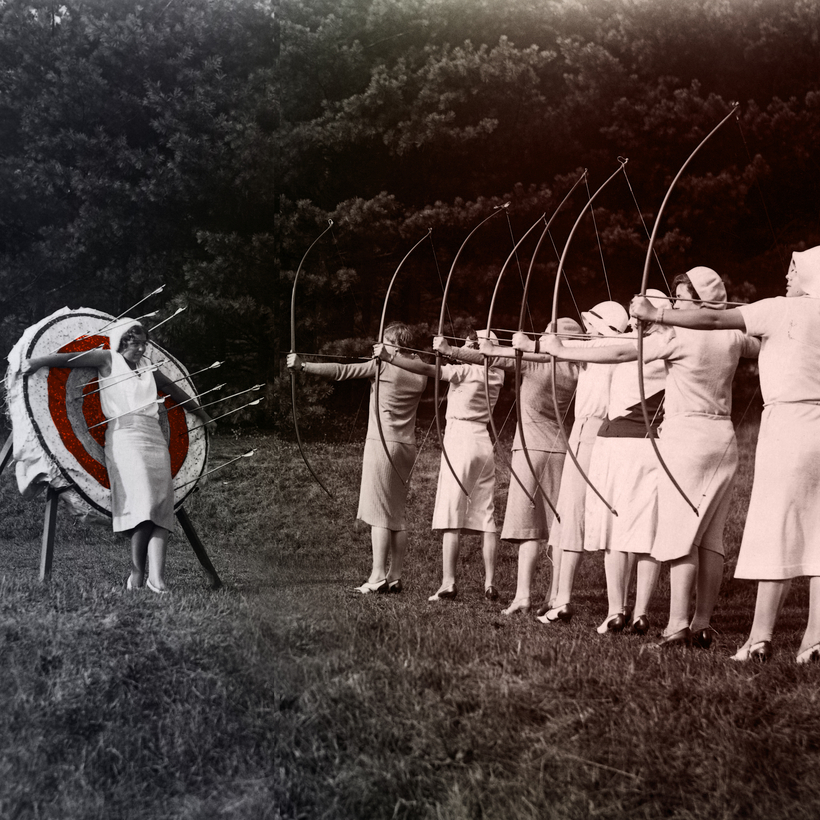

You already know their names: Maddy Moelis and Sierra Tishgart (Great Jones), Rachel Hollis (Girl, Wash Your Face), Audrey Gelman (the Wing), Steph Korey (Away), Ty Haney (Outdoor Voices), Leandra Medine Cohen (Man Repeller), Jen Gotch (Ban.do), Christene Barberich (Refinery29).

Their public disgrace became a form of entertainment for those of us with a work-from-home pandemic lifestyle that allowed us to be online pretty much all the time. Their downfalls felt participatory, an augmented-reality game you could play on your phone by toggling between different angry comment threads. Direct-to-consumer brands sold us scented candles and adaptogen tonics while we scrolled.