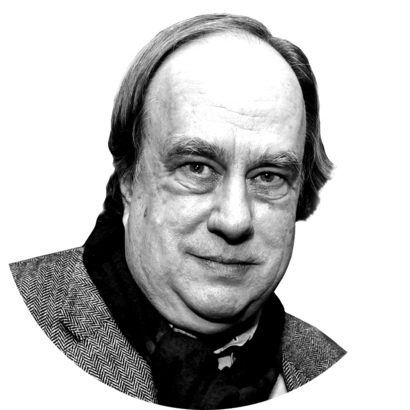

James Ellroy carries the sordid history of Hollywood in his hip pocket, like a flask of bootleg hooch. Best known for the first L.A. Quartet (The Black Dahlia, The Big Nowhere, L.A. Confidential, White Jazz) and the harrowing memoir My Dark Places, Ellroy writes like a red-eyed marauder, spurning the rich metaphors and blue moods of Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald to spit hot rivets in staccato bursts.

Noun-verb-sock-to-the-jaw, that’s his dominant rhythm, as the action drives like a prowl car up and down every garish street. Delivering the lowdown dirty on the City of Angels, Ellroy knows where all the skeletons are stowed and where all the innocent or inglorious dead are buried, and digs them out to do a Halloween dance across the voluminous pages of Balzacian epics of murder, vice, municipal corruption, police brutality, and peephole ethics.