The great German footballer Franz Beckenbauer once claimed that “football unites people around the world every day.” Never has this been more clear than in the last two weeks. Because while it’s true that recent footballing events have brought everyone—players, managers, fans, pundits, politicians, the sport’s entire global governing body—together like never before, it’s also true that what unites them is their hatred of where the sport is headed.

The culprit is the European Super League, a greedy little idea that died in agony approximately 48 hours after it was announced last week, when it was pummeled by a carpet-bombing of public disgust.

Before you can understand the European Super League, you first need to know how league football normally works. Imagine a pyramid. At the bottom of the pyramid are dozens and dozens of minuscule community clubs, and at the very top are the big-name franchises such as Manchester United and Real Madrid. If a team at the bottom of the pyramid does well, it will rise up a tier; conversely, if a big team performs badly, it will be relegated downward.

This means that, with a combination of smart choices, wise investments, and a dusting of good fortune, the smallest club on the Continent could one day end up winning the biggest prize in European football, the Champions League. Theoretically, league football is the perfect model of meritocracy. It’s the American Dream come true, albeit with dirtier knees and a curious accent.

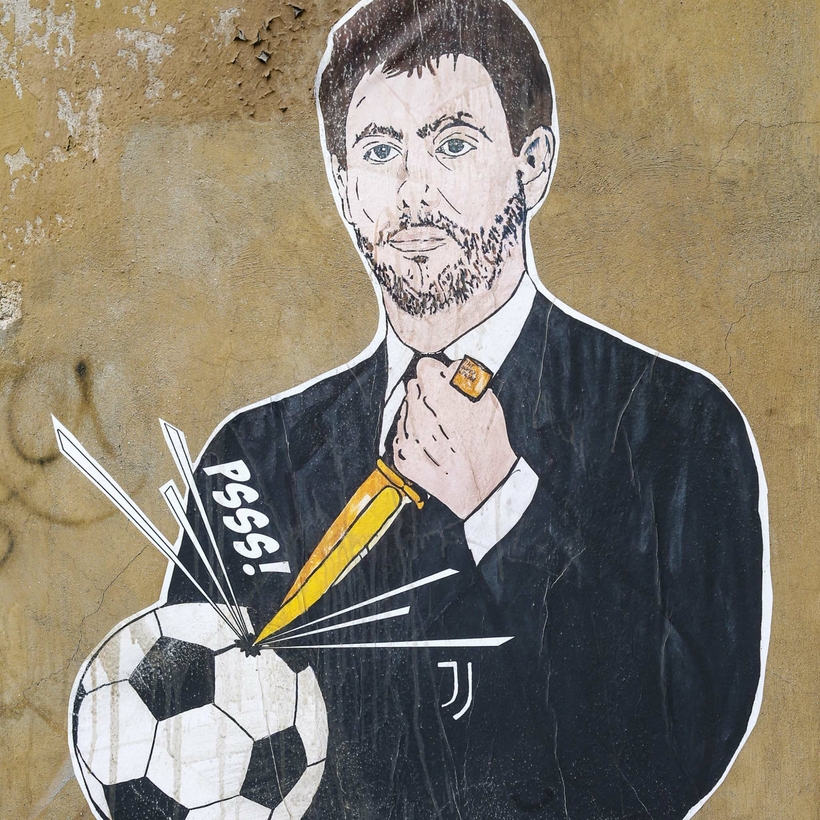

However, on Sunday, the tip of the pyramid decided to slice itself off. Rumors began to spread that 12 of the biggest clubs in Europe wanted to break away and form their own European Super League. These clubs, forever locked into the same elite group, would play each other again and again throughout the year, in a competition designed to have no real stakes other than the $4 billion that J. P. Morgan had committed to plowing into it.

The 12 clubs would never be relegated into a lower league or promoted into a higher one. It’s nothing like a meritocracy, just a cordoned-off money pit where Europe’s richest and most powerful clubs could splash around untroubled by anything as piffling as competition.

The result would be something like the N.F.L. or the N.B.A., a walled garden where club owners are handed more money and power than they could ever dream of. It is, to paraphrase a recent James Corden monologue, as if Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks were to set up a Super Oscars to make sure that they would be the only people nominated each year.

It’s a very American business model, which shouldn’t be a surprise, because European football is now a very American business. Of the five proposed leaders of the Super League, three—Manchester United’s Joel Glazer, Liverpool’s John W. Henry, and Arsenal’s Stan Kroenke—are American. In addition to the football teams, Glazer also owns the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, while Henry owns the Boston Red Sox, and Kroenke owns the Los Angeles Rams; the Denver Nuggets; the Colorado Avalanche, Mammoth, and Rapids; and two e-sports teams (professional competitive video gaming).

And here, among other things, is the problem. The Super League confirmed the worst fears of most football fans—that their lifelong clubs had become nothing more than portfolio items for self-interested foreign billionaires with little regard for the local community. It’s no secret that the upper echelons of the sport had been turning into vehicles for untrammeled capitalism, ever since Roman Abramovich—billionaire Russian oligarch and Vladimir Putin confidant—purchased lowly Chelsea F.C. with the intention of turning it into a global Über-brand. Nevertheless, the European Super League plans made this undeniable.

Very quickly, the sport turned on the clubs. The Union of European Football Associations (U.E.F.A.), which is the administrative body for European football, warned that any team competing in the European Super League would be banned from all other club-football competitions, and that their players would be prevented from competing in any World Cups. Other clubs released stinging statements, and their players began to put on Football is for the fans shirts during their warm-ups.

Clubs had become nothing more than portfolio items for self-interested foreign billionaires.

Boris Johnson called the league a “cartel” and promised a “legislative bomb” to stop it from happening. Jürgen Klopp was so blindsided by the news that he couldn’t control his anger. And he’s Liverpool’s manager. He was quick to point out that he and the players had “nothing to do with it.” Hundreds of fans broke coronavirus regulations to stage mass protests outside stadiums. Prince William wrote a tweet. The whole thing was spectacular.

And, ultimately, the pressure became too much. Abramovich’s Chelsea wobbled first, announcing its intention to withdraw from the Super League early on Wednesday. The other British clubs followed shortly after, and within a few hours the dream was dead.

Where football goes from here is anyone’s guess. There is still palpable anger that the league was even considered in the first place. Smaller clubs, who rely on subsidies from their larger cousins, could have been wiped out. Fans, who suddenly found themselves looking at expensive overseas trips to watch their teams, will be slow to trust again. There is even talk that British clubs might be given a German-style overhaul, where fans are handed 51 percent control to stop this sort of thing from ever happening again. Even J. P. Morgan has suffered, with a sustainability-rating agency downgrading the firm from “adequate” to “non-compliant.”

But, still, the danger is there. The European Super League has been whispered about for 20 years, so the likelihood is that this is more of a deferment than a destruction. And don’t forget that football is still controlled by men with vested interests, from the billionaire owners to the brazenly corrupt governing body, FIFA, which was torn apart by an F.B.I. racketeering investigation six years ago. Nevertheless, for now, football remains for the fans. That is, at least the fans who can afford the expensive sports-channel subscriptions.

Stuart Heritage is a Kent, U.K.–based Writer at Large for AIR MAIL