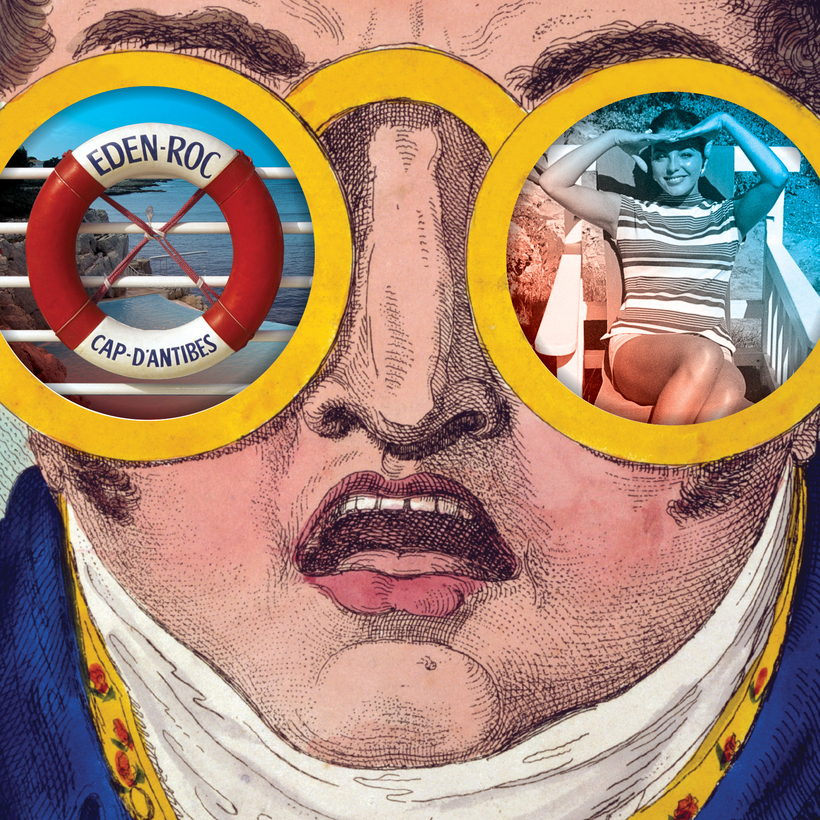

I will say right from the outset that the dinners I threw at the Hôtel du Cap over the years—and I held a number of them—were evenings of such pleasure and exuberance and glamour that, had I not been the host, I would most certainly never have been invited.

I can also say from the outset that, over the past quarter of a century, I have developed a fondness for the hotel to such a degree that it feels like a second home—one far superior to my first home—as indeed it has been for the iconic figures of so many passing eras, from the Belle Époque, through the Jazz Age, the jet age, the 1960s and 70s, right up to the present.