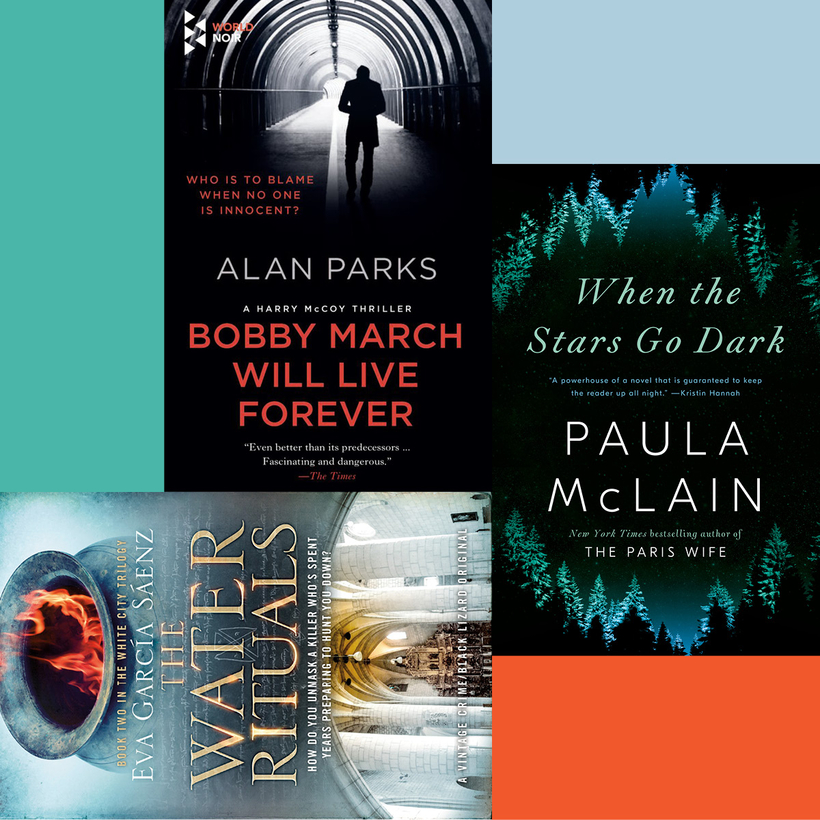

The mood is pretty grim in Scottish writer Alan Parks’s version of Glasgow in 1973. The poverty, dreary weather, 24-hour drinking, casual heroin use, organized crime, and a creepy gang of Clockwork Orange re-enactors give the impression of a city that’s given up and caved to its worst instincts.

But they’ve still got rock ’n’ roll, so it’s all the more depressing when Bobby March, a homegrown, if has-been, rock star, overdoses in a hotel room and the jaded populace barely blinks an eye. Instead, that collective eye is firmly fixed on the unfolding saga of young Alice Kelly, who has been kidnapped and is feared dead by thousands of mesmerized Glaswegians. Trying to sort this out, along with a few other problems, is Detective Inspector Harry McCoy of the Glasgow Police, who’s not assigned to the Kelly case but keeps his hand in nonetheless. McCoy is a classic noir cop, basically decent but well acquainted with the city’s underground and comfortable operating in the shadows to bring about an acceptable result. Moral ambiguity is baked into his job and his character.

Several combustible plotlines keep McCoy almost frantically busy, but the sad specter of Bobby March is ever present in the background. Parks, who used to work in the music business and clearly knows it cold, traces March’s career from his first recording session at 16 to his audition for lead guitarist of the Rolling Stones. He captures the buzz of playing in clubs and the grind of touring, with its cheap hotels, hangers-on, and obliging drug dealers, who keep reality at bay for another night and then, inevitably, forever. As a symbol of one of the few means of escape for Glasgow’s marginal youth, March’s trajectory from semi-stardom to oblivion to a resurrection of sorts ultimately offers a wee, wry glimmer of hope.

It happened in 1993, so awareness of the impact of the kidnapping and murder of 12-year-old Polly Klaas has faded. At the time, the nightmare of a middle-school girl snatched from a slumber party in Petaluma by a stranger froze the blood of American parents, unleashing a massive search and subsequent deluge of support and grief when a suspect confessed to strangling her.

When the Stars Go Dark takes place at the same time just up the Northern California coast in Mendocino, where a local girl has gone missing but isn’t drawing Klaas-level attention, partly because of her famous-actress mother’s desire for privacy. Teenage Cameron Curtis was going through a rough time due in part to her adoptive parents’ rocky marriage, so it’s possible she just ran off. But the more San Francisco detective Anna Hart learns about the introverted girl, the less sense that scenario makes. Having come up through the foster system herself, she recognizes Cameron’s kind of trouble and how vulnerable she could be to a certain type of predator.

Anna had just gone through an unspecified family trauma herself, and was taking a solitary time-out near where she grew up in Mendocino when she ran into the local sheriff, an old friend who asked her to help with the investigation. While working from Petaluma’s playbook to get the community involved, Anna also runs down every man in Cameron’s life and engages in a wrenching struggle with her own demons.

Paula McLain is probably most known for The Paris Wife, her best-selling novel about Hadley Richardson’s marriage to Ernest Hemingway, so this is new territory for her. She brings to it her heroine’s fierce commitment and personal experience in foster care as well as a few detours into the woods outside of quaint Victorian Mendocino that provide a breather from the story’s general intensity.

Picking up where you left off is always tricky for the writer of a series. Most are discreet, weaving in need-to-know details and plot points from the previous book as subtly as possible. Not Eva García Sáenz. Right from the start of The Water Rituals, the second book of a trilogy, we learn that some crazy things happened at the end of the first book, The Silence of the White City. Our protagonist, the wonderfully simpatico Inspector Unai López de Ayala, was shot in the head and rendered mute months earlier by the prolific serial killer he’d finally caught. Now on leave, the profiler has just learned that his girlfriend/boss is pregnant, but the identity of the father is an open, and fraught, question. So Ayala’s in quite a state. But when he’s called unofficially to the scene of a murder with ritualistic overtones and a personal connection, he decides to sign up for speech therapy and get back in the game.

In the summer of 1993, Ayala and three other boys from Vitoria, Spain, went north to coastal Cantabria on a student archaeology trip also attended by an inky-haired young artist who called herself “Annabel Lee” and bewitched the four friends. Twenty-four years later, a pregnant Annabel has been found near Vitoria, hanging upside down from a tree with her head immersed in an ancient Celtic cauldron filled with water. But the trip’s relevance to the murder is unclear until one of the old high-school group is found dead in a similar situation.

While the seductive magic of Vitoria and its denizens’ sexily intertwined relationships continue to animate the series, this book’s focus shifts to Cantabria, landing on a dark tale informed by Iberian history and myth. Families can really mess you up, and in this department, the ancient Greeks have nothing on Sáenz’s modern-day Spaniards.

Lisa Henricksson reviews mystery books for AIR MAIL. She lives in New York City