A Light in the Dark: A History of Movie Directors by David Thomson

Let’s face it, David Thomson is probably the very best film critic-historian currently writing. And writing: his huge (1,168 pages, small type), extraordinarily detailed and beautifully executed New Biographical Dictionary of Film: Sixth Edition all by itself would be profoundly impressive enough. But Thomson has published maybe a dozen other equally valuable—each in their way—film books.

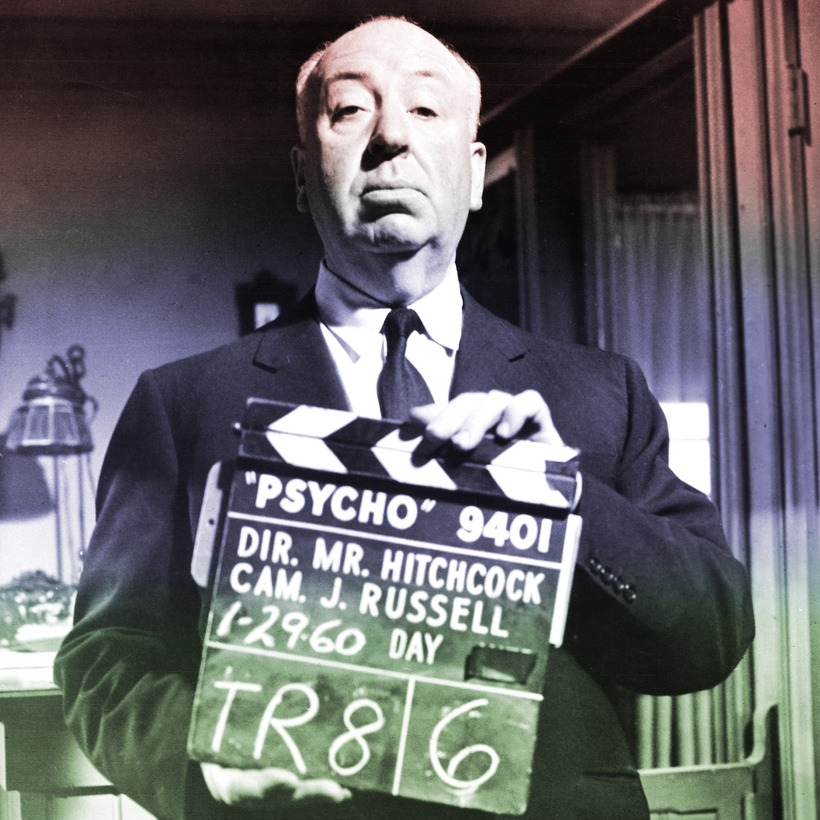

His newest has an evocative title with a clear double meaning: A Light in the Dark, subtitled A History of Movie Directors. Indeed, this work takes us through virtually all the widely varying qualities that directors have possessed—or should possess.