I once toyed with the idea of taking up Scientology. I had no illusions that it would enable me to run up the sides of buildings like Tom Cruise or hone my brain into a perfect diamond, though either would have been neat. I just thought it might give me the locked-on-target focus to cut through the everyday dribdrab.

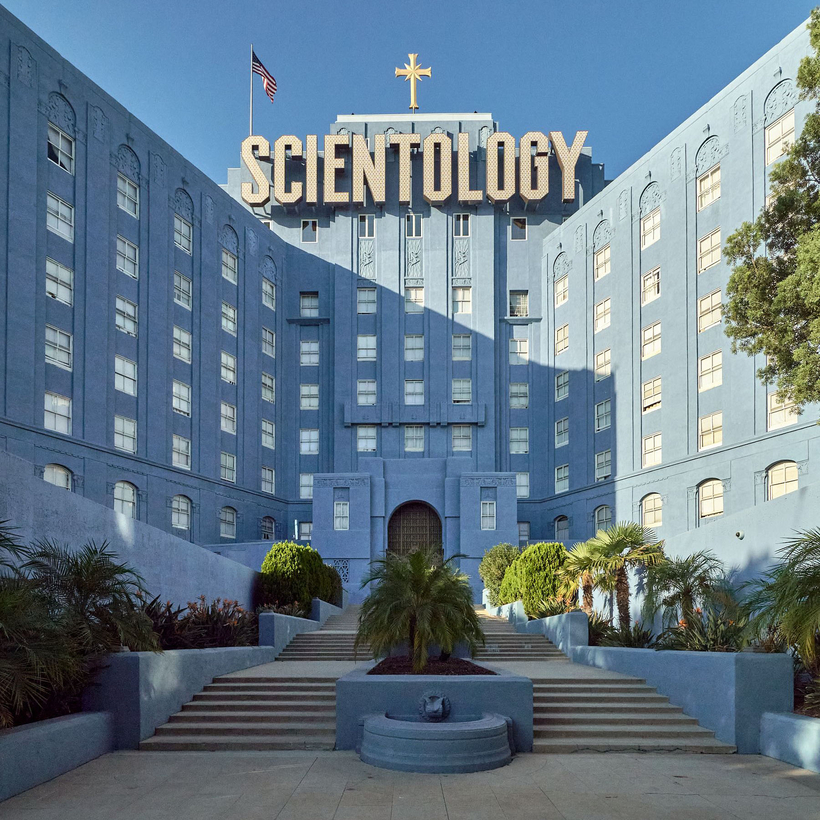

More than once I passed the Church of Scientology in Times Square and was tempted to pop in for a “free tour” and pick up a few colorful brochures without being abducted. What disabused me about signing up for an introductory course was not only Scientology’s culty reputation but the realization of how much work was involved in becoming a practicing Scientologist. All that studying, auditing, testing, rigorous cross-examination, and mastering of arcana to facilitate the long trek across what Scientology called “the Bridge to Total Freedom”—it seemed a bit much, frankly, closer to pursuing a graduate degree than achieving immortal incandescence. So I decided to dabble elsewhere, though Scientology continued to fascinate me as a phenomenon with its scope, reach, cultural imprint, eruptive scandals, and determined place as the world’s most successful modern religion.