On a winter night in 2001 at Manhattan’s storied Algonquin Hotel, friends and business partners Charles Ardai and Max Phillips were parked at the bar. The two were getting pleasantly soused to celebrate the sale of Juno—an early Internet service they’d created—to one of their competitors. As they looked forward to a newfound sense of freedom, discussion turned to what was next in their lives.

“Maybe some literary ghosts were listening and whispering in our ears, since the talk turned to old paperbacks,” says Ardai, who along with Phillips is a passionate fan of the pulp magazines and books once ubiquitous from the 1940s through the 1960s. You know the type—35-cent, pocket-size reads with lurid cover paintings that used to line those wire spinner racks at the local drugstore; lean crime novels that wasted no time in getting straight into the seedy action promised by the sexy artwork.

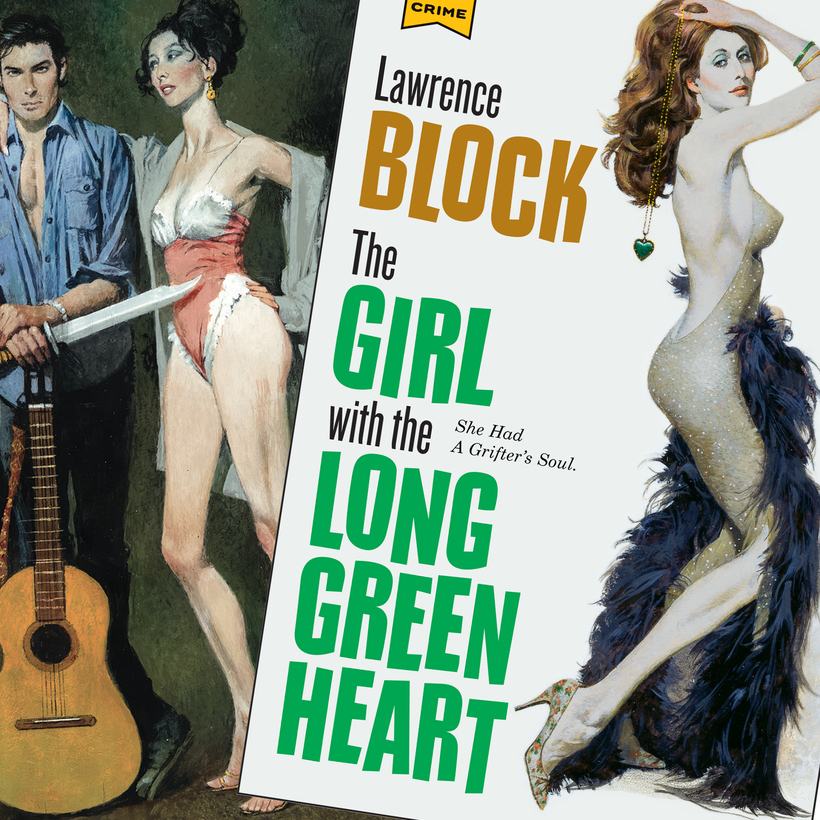

“Paintings of beautiful women, danger, intrigue—what’s not to love?” says Ardai. “When I was a kid, my father had a shelf of the old Mike Shayne private-eye paperbacks by Brett Halliday, with their gorgeous painted covers: sultry, impossibly leggy women with defiant stares, plunging necklines, and the occasional pistol or stiletto in hand. Even when I was 10, 11, 12, I ached to find out who these women were and what they wanted so intensely.”

Back at the Algonquin, Ardai and Phillips were wondering why no one seemed to publish such books anymore, which led to them asking each other, “Why don’t we do it ourselves?” Both of them enjoyed writing, and Phillips happened to be a crackerjack graphic designer. (Phillips’s bread and butter is working as one of Dublin’s top designers at Signal Foundry, a well-respected typographic-drawing office he’s the proprietor of.)

What could have been a mere alcohol-assisted hypothetical remained on their minds, though, and after three years of pitching they finally found Dorchester Publishing, who was interested in their improbable dream of reviving aesthetically faithful hard-boiled paperbacks. Established in New York City, they called their imprint Hard Case Crime. And in 2004 their first six titles were released, two per month for three consecutive months. One was a reissue of a neglected, out-of-print novel from the golden age of pulp, and one newly written in the old style. (Two of the debut releases were written by Hard Case Crime’s founders themselves, Ardai’s under the nom de plume “Richard Aleas,” a perfect anagram of his name.)

Phillips designed the period-accurate covers, with newly commissioned oil paintings from artists both young and old, including the still-living legend of the genre Robert McGinnis. The look was so authentic, it generated poignant nostalgia for the old-timer writers they were reaching out to.

“Early on, we were in touch with Mickey Spillane, who was well into his 80s at that point, and we showed him some samples of our covers, and he just lit up,” says Ardai. “He sent us a note: ‘Those covers brought me right back to the old days.’ Donald Hamilton, the creator of Matt Helm, told us, ‘The art perfectly captures the era—if I didn’t know better, I would have sworn it was from one of the old publishing houses.’ Our goal was for Hard Case Crime to look like a company that had started publishing books like these in 1945 and just somehow never stopped.”

The mission to pay reverent, straight-faced homage to the style of the pulp era, minus modern-day irony, pastiche, or spoof, appeared accomplished in short order.

“If the whole adventure had stopped there, I would personally still have considered it a success,” says Ardai. But that first six-pack of Hard Case Crime books got an unexpected volume of media attention, with everyone from USA Today to Vanity Fair spotlighting their cover art. What had initially seemed like a niche longing for titillatingly retro paperbacks turned out to have a broader appeal than had been anticipated.

As for the literature itself, when all six releases were nominated for or won awards, Ardai and Phillips seized the momentum and released another set of six novels. “Maybe it would’ve stopped there, except that Stephen King wanted to get in on the fun, and wrote book No. 13 for us,” says Ardai. At that point there was no turning back.

How did one of the best-selling authors of all time end up writing new material for a boutique imprint just one year into its existence?

“I reached out to Stephen King early on because I knew from things he’d written and said that he loved old paperback crime novels as much as we did,” says Ardai. The humble request submitted was to gauge whether or not King would be willing to lend his name for a blurb to use on a Hard Case Crime cover—the association would surely help promote a lesser-known writer’s novel in their burgeoning collection.

“I sent off a package of sample materials like a boy throwing a bottle into the ocean with a message inside it, not expecting that I’d ever hear back,” says Ardai.

Several months went by, when finally Stephen King’s agent rang. The bad news? King didn’t want to write a blurb for them. The good news? King wanted to write a book for them instead.

“I was dumbstruck. Didn’t know what to say, didn’t know what to do,” says Ardai. “The giddiness came later. In the moment I was just doing an involuntary Jackie Gleason impression: Homina homina homina … ”

King’s book, The Colorado Kid, was released in 2005 and became a best-seller. It more or less single-handedly paid the bills at H.C.C. for several years, bringing the company more mainstream attention than they’d thought possible. Eight years later, King’s agent said he had written another book that might be a good fit.

“Good Lord. That book was Joyland, which to this day a lot of people rank among their favorite Stephen King novels of all time,” says Ardai. Like clockwork, another eight years go by and this time, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, King did it yet again, this time offering Later, which Hard Case Crime published this past March. “He’s like our guardian angel,” says Ardai. “Nothing I say can come close to expressing what his contributions have meant to us.”

Of the 140 or so books published thus far by Hard Case Crime, roughly half have been sourced from old unpublished manuscripts (for example, Samuel Fuller’s long-lost novel, Brainquake) or out-of-print favorites in Ardai’s personal library (a dozen gems from Donald E. Westlake, including Forever and a Death, originally commissioned as a James Bond screenplay), with the other half comprising new texts (including Brian De Palma’s debut work of fiction, Are Snakes Necessary?). Every single release comes with a brand-new racy oil painting, even for the odd reprint within its own catalogue. “The covers are designed to catch your eye and quicken your pulse and loosen the money in your wallet,” says Ardai.

A genuine labor of love, since zero people are employed by Hard Case Crime.

“It’s just me, working part-time, without drawing a salary; everyone else is freelance,” says Ardai. “If you took our firm-wide profit in a typical year and divided it by the hours I spend editing and typesetting and proofreading our books—not to mention writing out royalty checks by hand, like Bob Cratchit at his ledger—you’d come up with an hourly rate of pay well below what I’d get flipping burgers at McDonald’s.”

At the moment, Ardai is particularly proud of Five Decembers, by relative newcomer James Kestrel, an impressive new work of fiction released in October. Ostensibly the book is a neo-noir circa 1941 that follows a Honolulu detective pursuing an overseas killer, but Kestrel—“formerly a bar owner, a criminal defense investigator, and an English teacher, [and] now an attorney practicing throughout the Pacific”—manages to pack in so much more than surface thrills.

“It may be the best book we’ve ever published,” says Ardai. “If we had to stop publishing Hard Case Crime tomorrow and Five Decembers were the last book we put out, I would feel we’d ended on the highest of notes.”

Looking ahead to the future of H.C.C., what would be Ardai’s dream texts to unearth? “A few weeks back I read about an unpublished werewolf novel by John Steinbeck, which his estate is refusing to allow anyone to publish,” says Ardai. “Supposedly there’s also an unpublished pulp Western written by Kazuo Ishiguro at the start of his career. And I can’t help wondering what Salinger had in that vault of his. Probably not a hard-boiled crime novel—probably not. But maybe … ?”

Spike Carter is a writer and filmmaker. His next project is a documentary about Eric Roberts