First, let me explain how long I have been waiting for this book. In the proposal I prepared in the spring of 2016 for The Real Lolita, my first nonfiction work, about the true story that informed Nabokov’s classic, I mentioned The Sinner and the Saint as a possible comparison title. The real-life case that inspired Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s 1866 masterwork, Crime and Punishment, written by Kevin Birmingham, the same author who had, in 2014’s The Most Dangerous Book, delightfully chronicled the various obscenity trials and tribulations of James Joyce’s Ulysses? I was already sold. Thankfully, the long march to publication was well worth it.

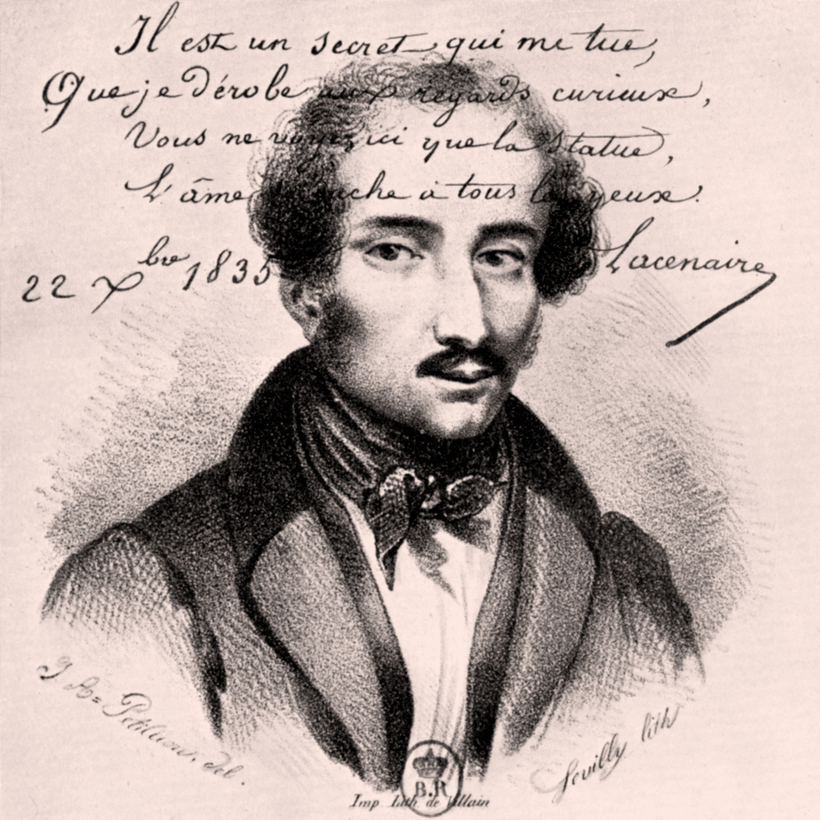

The “real-life case” in question concerned the deeds of Pierre-François Lacenaire (the surname fittingly suggests larceny at its heart), a Parisian author, manipulator, and eventual murderer whose crimes, for which he was ultimately executed, scandalized the city in the mid-1830s—and caught the retrospective attention of Dostoyevsky, whose early literary success with his debut novel, Poor Folk (1846), had been pulverized by radical politics, imprisonment, hard labor, physical maladies, the agonizing deaths of loved ones, and a vicious gambling addiction that yoked him to writing as a means of naked survival. As he once wrote, “Yes, if it’s impossible to write I will die.”