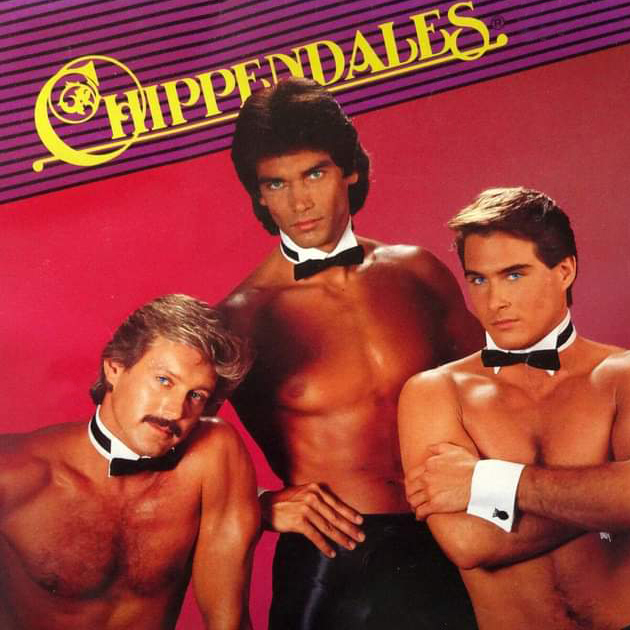

It’s 1985 and a thousand women are gathered together in a steamy venue in New York. They are secretaries, suburban mothers, here for a girls’ night out. Around the hall are topless waiters wearing Spandex pants, collars and cuffs, their oiled muscles glinting in the show lights. Some of them have dollar bills sticking out of their pants and lipstick marks smeared across their torsos. As the curtain begins to rise for the main show, women’s voices ring out through the auditorium: “We want meat! We want meat! We want meat!” Welcome to the Chippendales.

“The women were out of line every night,” says Scott Marlowe, 60, a dancer at the time. “Women had never been able to behave like that before. There were no men in the audience and they were able to say, now it’s our chance. Unsurprisingly, they behaved more aggressively than men did.”