It’s a good idea to get into a person’s head. If, for example, you are trying to find something that’s been hidden—let’s say a man, in the midst of financial trouble and a bad divorce, complete with child-custody brouhaha, killed his wife, but her body has not been found—you might want to get in your car and retrace the route the presumed killer took that day, see what he saw, look at what he looked at, and possibly catch a detail missed by all those F.B.I. agents, cops, helicopters, cadaver dogs, surveillance cameras, and forensic teams.

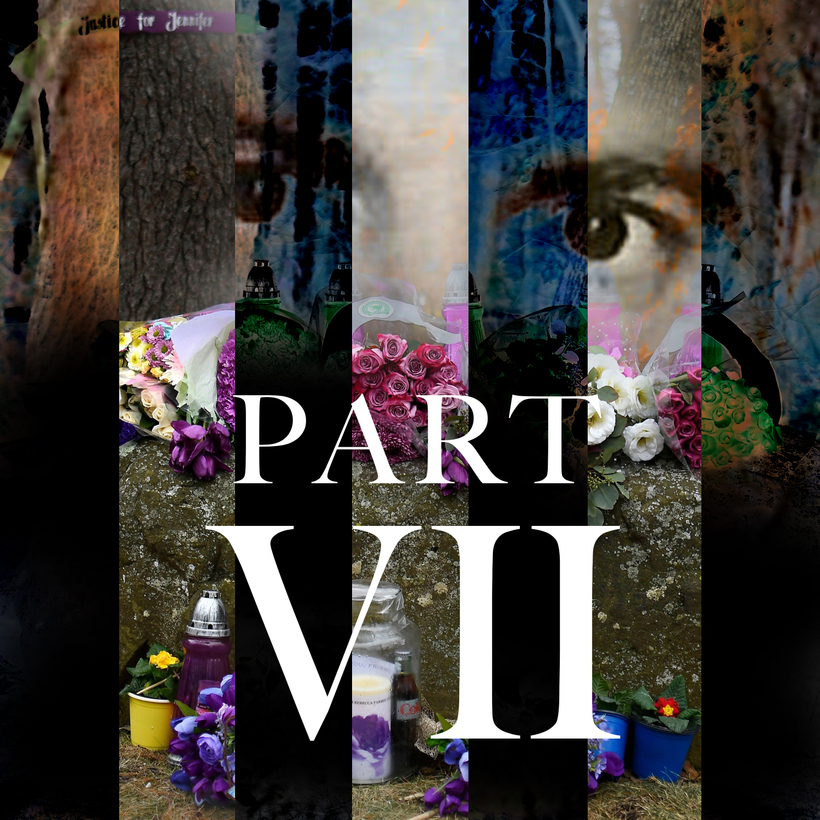

Jennifer Farber Dulos, New York City transplant, mother of five, playwright, memoirist, and scion of a great fortune, vanished on the morning of May 24, 2019, after dropping her kids off at the New Canaan Country School.