The fall from grace began with a stumble.

In April 2012, on a holiday in Botswana, King Juan Carlos of Spain was walking up a set of steps when he slipped, fell—and broke his hip. The fracture was excruciating for the 74-year-old monarch. But there would be little time for sympathy. As the king was whisked back to Madrid by private jet for treatment, the full gory details of his until-then-secret jaunt began to emerge. Almost immediately, it was revealed that he had been visiting Botswana for a high-end safari-hunting trip; that he had been accompanied by a German-Danish mistress; that he had been bankrolled by a shadowy Saudi Arabian tycoon; and—worst of all—that he had been shooting elephants for sport.

The injury, it soon became clear, was nothing compared with the insult. Juan Carlos, who this week reportedly fled to Santo Domingo while under criminal investigation, had tripped up.

The safari would have been a bad look at the best of times—after all, the king was the honorary president of the Spanish branch of the World Wide Fund for Nature. But in the depths of a historic economic crisis—with the unemployment rate hitting 24 percent—the trip was a national disgrace. An online petition calling for the king’s resignation from the W.W.F. quickly gathered some 85,000 signatures. The Spanish press, long indifferent to the monarch’s apparent philandering, extravagant spending, and murky deal-making, could turn a blind eye no longer.

He had been accompanied by a German-Danish mistress; he had been bankrolled by a shadowy Saudi Arabian tycoon; and—worst of all—he had been shooting elephants for sport.

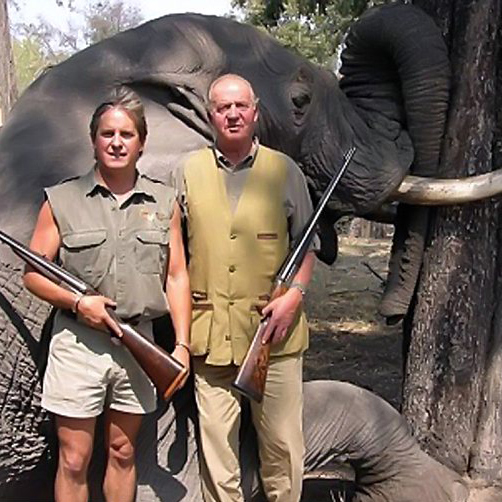

Pictures of the king on an earlier hunting trip—posing with a rifle in front of a dead, slumped African elephant—were soon plastered across the national papers. The Socialist Party leader in Madrid, Tomás Gómez, suggested that he should choose between his “public responsibilities or an abdication.” As he left San José hospital in Madrid later that week, the king offered a timid mea culpa to his people—his first-ever public apology. “I’m very sorry,” he said. “I made a mistake. It won’t happen again.” And that, Juan Carlos probably thought, would be the end of it. It is now clear, however, that it was only the beginning.

In 2018, a Swiss prosecutor named Yves Bertossa—prompted by the renewed scrutiny of Juan Carlos’s louche lifestyle and a series of secret recordings of his lover—began to investigate the former king’s financial arrangements. (Juan Carlos had abdicated the throne in 2014, following ill health and persistent rumors around his personal indiscretions.) Bertossa’s investigation, which is ongoing, quickly zeroed in on a $100 million payment made to King Juan Carlos by the (now late) king of Saudi Arabia, a decade earlier, in 2008. Specifically, Bertossa was sniffing around to see if this “gift” had anything to do with an $8.9 billion contract awarded to a Spanish consortium for the building of a high-speed rail link between Medina and Mecca.

The money, Bertossa discovered, had been paid by the late King Abdullah into a Panama-based offshore fund called the Lucum Foundation. The fund was liquidated in 2012, but not before its $73 million balance was transferred to one Corinna zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, a German-born businesswoman—and the very same lover who had accompanied King Juan Carlos to Botswana on his ill-fated hunting trip. Ms. zu Sayn-Wittgenstein claims that she possesses a document signed by the former king which decrees the payment an “irrevocable gift” to her, not a money-laundering ploy. She also says she paid money back into the account after it had been loaned to her to buy a pair of chalets in the Swiss resort of Villars for her and Juan Carlos.

A $100 million payment made to King Juan Carlos by the (now late) king of Saudi Arabia, a decade earlier, in 2008.

Soon, Bertossa uncovered a second fund—the Fondation Zagatka, based in Liechtenstein. This time, its sole beneficiary was Álvaro d’Orleans-Borbón, a distant cousin of Juan Carlos’s. The former king had consistently denied that he had squirreled away a huge fortune via the proxy of his cousin. But the fund’s transactions seem to indicate otherwise. As The Telegraph reported, King Juan Carlos racked up a $6 million bill for private jets between 2016 and 2019—including flights to the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix and the Dominican Republic. This was apparently settled through the Zagatka fund by d’Orleans-Borbón, who lamely declared that he had paid for the jets out of a sense of “family tradition.”

And then there was the briefcase. As the investigation burrowed deeper, Bertossa discovered that, in 2010, the king had allegedly been given $1.9 million by the king of Bahrain, Hamad bin Isa al Khalifa. According to El País, Juan Carlos had then personally flown to Switzerland, knocked on the door of his wealth manager Arturo Fasana—and handed him an attaché case filled with the millions in cash. Fasana then deposited the money into a Swiss bank account belonging to an offshore fund tied to the king’s name. This is royal protocol as imagined by Martin Scorsese.

Between the offshore accounts and the bulging briefcase, a damning picture began to emerge: of a former king with a vast, secret fortune hidden in a web of murky funds from Panama to Switzerland to Liechtenstein; of a decadent potentate using his chummy Gulf relations to secure kickbacks from multi-billion-dollar construction projects; of a monarch without any sense of decorum or propriety.

A case in point: that troublesome $100 million payment. According to papers filed in Spain’s Supreme Court, Juan Carlos’s financial adviser—a bank manager in charge of Lucum’s account at the Swiss bank Mirabaud—said the king was “very surprised” at the size of the “gift” and was “expecting something in the order of a fifth of that amount,” according to The Telegraph.

A decadent potentate using his chummy Gulf relations to secure kickbacks from multi-billion-dollar construction projects; a monarch without any sense of decorum or propriety.

But the court papers also reveal that the Spanish consortium involved in the Medina-Mecca line agreed to dole out more than $256 million in commissions to other parties involved in the deal (including Shahpari Zanganeh, the widow of Adnan Khashoggi, the billionaire arms dealer), much to the king’s chagrin. A secret recording from 2015 appears to show Corinna zu Sayn-Wittgenstein mimicking Juan Carlos bemoaning his lack of a kickback. “The king said: ‘What the f**k, my commission, I made the train deal. I spoke to my friend—my brother in Saudi,’” she can be heard to say.

These recordings of zu Sayn-Wittgenstein are not so much a smoking gun as a billowing armory. The tapes first came to light in 2018 when they were published by the online newspaper El Español, and appear to give substance to the vague rumors that had long swirled around the former king. They document a series of conversations that took place in London in 2015 between zu Sayn-Wittgenstein and José Villarejo, a rogue former police investigator who is currently in pre-trial custody on charges of bribery of public officials and money-laundering and who denies the accusations. Villarejo’s decades-old party trick, it seems, was to collect kompromat on influential public figures via secret recordings. As The New York Times put it: “The retired police commissioner may well have dirt on just about everyone who is anyone among Spain’s political and business elite.” And the king, it has become clear, can now count himself in that dubious company.

In the tapes, zu Sayn-Wittgenstein is heard grumbling about Juan Carlos’s ham-fisted money-laundering schemes. In one instance, she describes being given a $3.3 million property by the king of Morocco, only to be quickly instructed to hand it over to Juan Carlos. (“They say ‘she doesn’t want to give things back.’ But if I do, it’s money-laundering and I’ll go to jail,” she complains.) In another, she accuses Spain’s C.N.I. intelligence agency of orchestrating a campaign of intimidation against her, because, as she later stated in a written affidavit, she was seen as a “threat to the Royal Family.” Later on, the former mistress identifies the king’s cousin as the proxy for his hidden wealth. (“They have put some things under the name of his cousin, who is Álvaro d’Orleans-Borbón. The accounts in Swiss banks have been put under his name.”) Most damningly, Ms. zu Sayn-Wittgenstein is heard to say, “The king has no concept of what is legal and what isn’t.”

The accuracy of that statement will now be put to a very public test. In March, a spokesperson for Podemos (one half of Spain’s coalition government) told El Confidencial that the party would call for a thorough investigation into a potential “case of corruption that affects the highest office of the state,” while Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez called the allegations “disturbing.” In June, Spain’s Supreme Court announced the beginning of their first-ever probe into the king’s activities, specifically in relation to alleged kickbacks from the Saudi rail project. Juan Carlos is constitutionally immune from prosecution for any act committed before his 2014 abdication. But investigators say they will “establish or rule out the criminal relevance of events occurring after June 2014.” The former king has no immunity in Switzerland.

Should a criminal charge of any sort be made, it will mark a new low point in Juan Carlos’s plummet from favor. The king was long seen as a national hero for his role in bringing democracy back to Spain following the death of General Franco, in 1975. But the Spanish monarchy became pockmarked by scandal and acrimony during the later years of his tenure. There was the incident where his 13-year-old grandson shot himself in the foot with a rifle. (According to Spanish law, children under 14 aren’t permitted to use firearms.)

Then there were allegations made by a Russian official in 2006 that Juan Carlos had shot dead a tame bear that had been doped with honey and vodka in the northwestern region of Vologda. (Royal officials dismissed the rumor as absurd, while The Telegraph reminds us that “giving a bear vodka in Russia is not illegal.”) And the moment in 2017 when the king’s son-in-law Iñaki Urdangarin was sentenced to more than six years in prison for using royal clout to bolster his private income in the Balearic Islands. (Urdangarin, a former Olympic handball player, had been vastly overcharging the local government to organize sporting events and construction projects.)

A book published in 2017 by historian Amadeo Martínez Inglés parallels Juan Carlos’s passion for hunting game with this ardor for pursuing women. The book, the Daily Mail reported recently, describes how the king would always bring three shotguns and a mattress on partridge shoots. When each gun had been discharged, the monarch would drop it on the mattress—where a team of assistants would retrieve it, reload it, and pass it back to him so that he might never miss a shot. The mattress, the book claims, would serve another purpose entirely once the carnage had ended. Indeed, Inglés estimates King Juan Carlos has tallied up around 5,000 sexual partners—and that his more publicized conquests (zu Sayn-Wittgenstein among them) are simply “the tip of a monumental sexual iceberg,” which could have yielded “more than 20” children. A 2012 book by socialite Pilar Eyre, which is also quoted by the Daily Mail, places the number at a more understated 1,500—but does include a salacious (and disputed) story in which Juan Carlos puts forth a “tactile” advance on Princess Diana on a yacht in 1986.

“The king said: ‘What the f**k, my commission, I made the train deal. I spoke to my friend—my brother in Saudi.’”

King Felipe, the current ruler, has not escaped this hereditary infamy. Juan Carlos’s oldest son had long been eager to cultivate a more dignified, understated profile next to his roué father. But in March it emerged that Felipe was listed as the hereditary beneficiary of the Lucum and Zagatka funds. He has since renounced any economic inheritance he might get from his father, and the royal allowance of $228,000 permitted to Juan Carlos (dubbed the “king emeritus” since his abdication) has been ceased. But the stain remains. The Telegraph revealed last month that Felipe’s multi-country, $500,000 honeymoon in 2004, for example, had been bankrolled by Juan Carlos and one of his old sailing buddies, Josep Cusí, himself a colorful figure among the Spanish elite. What’s more, the zu Sayn-Wittgenstein tapes allege that Juan Carlos paid for most of the family’s expenses “in cash,” and would return to the royal Zarzuela Palace from “Arab countries” with “sometimes … five million” in a suitcase. This would then be added up, apparently, on Juan Carlos’s personal money-counting machine—a process in which he was said to take a “child-like” glee. The former king’s obsession with money, she says, is like an “illness.”

Finally, on Monday of this week, Juan Carlos hit Eject. In a written statement, the former king announced his “considered decision to move outside Spain at this time” in the face of the “public repercussions that certain past events in my private life are generating.” The statement made no mention of Juan Carlos’s final destination, but La Vanguardia, a Spanish daily newspaper, believes he traveled from Sanxenxo, in Pontevedra, to Porto, Portugal, on Monday morning, before boarding a plane to Santo Domingo, in the Dominican Republic. There, the paper claims, he’ll be a guest of the Fanjul family—Cuban-born sugar-and-real-estate barons—at their high-end Casa de Campo resort for “a few weeks.” (State broadcaster RTVE, meanwhile, claimed that unnamed royal sources had said the former king wants to return to Spain soon, and other media outlets have reported he is still in Portugal as the guest of the aristocratic Brito e Cunha-Espirito Santo family, who are old and loyal friends.)

Despite the apparent distance, Juan Carlos’s lawyer said, the former king would “remain at the disposal of the prosecutors’ office.” The Dominican Republic, it should be noted, is classified by Switzerland as a “very difficult” judicial cooperator.

The stated aim of this self-imposed exile is to allow Felipe to continue in his role with “tranquillity and calmness.” Such tranquility, however, is by no means guaranteed. Back in March, at the beginning of the coronavirus-pandemic lockdown, King Felipe appeared on national television to give a speech to his subjects. It urged calm, decorum, and unity—but made no mention of the roiling palace scandal. That night, affronted by the silence, citizens took to their balconies, courtyards, and doorways to bang pots and pans in thunderous protest. As the trial deepens, the clamor will grow.

Joseph Bullmore is an Editor at Large for AIR MAIL