If the English are branded on their tongues, then people in Northern Ireland are defined less by how they speak than by what they say. Even the statelet’s name is a source of friction. Irish republicans (who are usually Catholic) speak of the “North of Ireland” or the “Six Counties” to signal that they do not recognize the legitimacy of British rule over their homeland. Unionists and loyalists (who are usually Protestant) prefer “Ulster,” thereby avoiding any mention of “Ireland.”

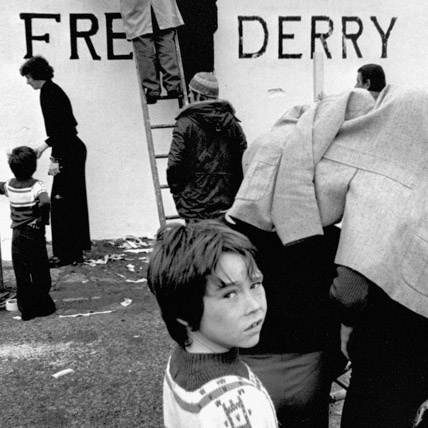

A central sticking point in that linguistic quarrel is the city of Derry, which unionists call “Londonderry,” leading some local wags to dub it “Stroke City.” Throughout the multi-sided ethno-nationalist conflict euphemistically known as the Troubles, which lasted from the late 60s to the late 90s, using the wrong name in the wrong company risked disaster.