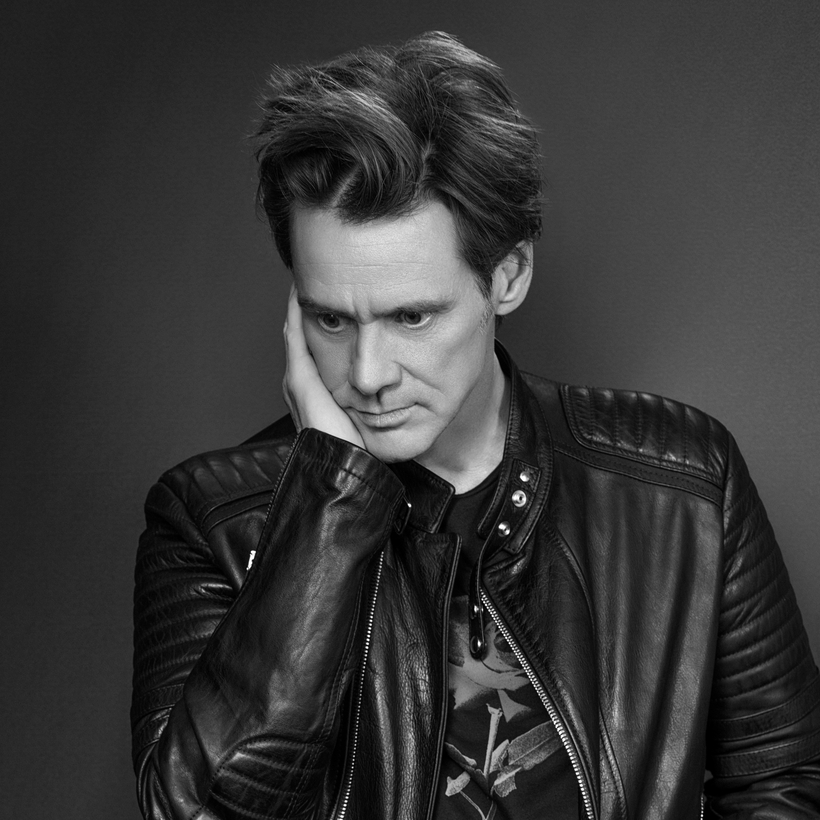

Oh, dear. I should have looked at the e-mail from my editor more closely. I thought I had been asked to review a memoir by Jim Carrey. Instead, I was asked to review a teasingly autobiographical novel co-written by Jim Carrey and titled Memoirs and Misinformation. The protagonist is a movie star named Jim Carrey, whom we meet holed up in his lonely Brentwood home, suffering some kind of emotional breakdown and/or existential crisis while binge-watching documentary series about Pompeii and predatory dinosaurs. The mood is portentous; so is the prose. Death is in the air. The Santa Anas, “those devil winds that sapped the soul,” are blowing. The book’s first sentence: “They knew him as Jim Carrey.”

Oh, dear. It’s written in the third person.

We put up with bad prose and self-absorption when we read celebrity memoirs because we want dish. Sometimes, depending on the celebrity, we also want insight into the talent and work that led the author to become famous in the first place. Jim Carrey has had a fascinating, idiosyncratic, and important career, and if he were writing a memoir and asked for my input, I would want to know about the ways in which childhood deprivation and the depression he’s endured as an adult have shaped his comic persona. I’d like to know what it was like to be “the white guy” on In Living Color, the 90s sketch-comedy show that put Carrey on the map. I’d like to know about working with the Wayans brothers and the Farrelly brothers and directors such as Michel Gondry, Milos Forman, Peter Weir, and Ron Howard.

That said, it is a critical faux pas to review the book you wish the author had written rather than the one in front of you, and I am reviewing a novel, albeit one that hints at playing peekaboo with revelation.

From the Man Who Brought Us Mergers & Acquisitions

Carrey’s co-author on Memoirs and Misinformation is Dana Vachon, a high-living former investment banker whose one previous book, Mergers & Acquisitions, is a bildungsroman about a high-living investment banker, so he knows the hall-of-mirrors genre. The new book isn’t even really half a memoir, as the title suggests, though Carrey is the protagonist and he interacts with many other movie stars and filmmakers, some of whom he definitely knows in real life, including Nicolas Cage, Kelsey Grammer, Charlie Kaufman, Anthony Hopkins, Goldie Hawn, Sean Penn, and Gwyneth Paltrow—but I doubt the real Paltrow has an online degree from M.I.T.

So, does Memoirs and Misinformation work as a novel? Not really. It’s not a catastrophe—there will surely be many worse novels published this year. It’s more like a beached whale: a curiosity with a tragic air to it, if you are sentimental, but in the end something that just lies there. Its pages are full of antic behaviors and misbehaviors that never cohere into character, while the plot meanders through scenes of familiar Hollywood satire and bathos to not much purpose or effect, though I did laugh when Carrey comes home one day and is dismayed to find his agent has messengered him the script for “Disney’s Untitled Play-Doh Fun Factory Project.”

There is also an unexpectedly poignant passage in which, while shooting a motion-capture film, Carrey acts with a virtual version of Rodney Dangerfield, the long-dead comedian who decades ago took a young, striving Carrey under his wing; you feel simultaneously the absurdity of movie make-believe and the genuine emotional ache that an actor like Carrey might draw on. This is one of several sequences where the novel skewers modern notions of personality as an ever more elastic commodity. But more typical is an episode where the star has an affair with a Marilyn Monroe impersonator who tries to kill herself with an overdose of his pills. If this were a memoir, the anecdote would be sad and tawdry but also—let’s be honest—titillating. As fiction … do we need Monroe exhumed yet again as a symbolic victim of show-business vampirism? At any rate, she’s soon shunted aside, having not registered with the reader of the novel much more than with the reader of this paragraph.

I doubt the real Paltrow has an online degree from M.I.T.

The last third of the book tumbles into comic absurdity, with an alien invasion that owes a debt to both Seth Rogen’s This Is the End and L. Ron Hubbard’s Battlefield Earth. (In a passing clever bit, Hollywood’s Scientologists feel validated by the invasion until events turn sour.) Paltrow, Penn, and Cage go blooey, but somehow Carrey survives—the last A-lister on Earth!—and the book’s final pages are devoted to a meditation on the illusion of selfhood:

What colossal labor. How exhausting, to be a self, to keep the Ponzi fed, with words, with feats, with playing at exceptionalism.

A moral, of sorts. I was reminded that Carrey’s previous book was How Roland Rolls, a children’s picture book about an anthropomorphic wave who conquers his fear of death by realizing he’s part of the “whole big wide ocean.”

I suspect one of Memoirs and Misinformation’s aims is to give us a sense of what it feels like to be Jim Carrey—beleaguered, simultaneously proud and insecure, discombobulated, spiritually exhausted, to judge from these pages—while sort of respecting his privacy. But it proves a self-defeating exercise when the book fails to give us much reason to care about “Jim Carrey” beyond whatever interest or affection we already have for the actual Carrey. If you are unacquainted with Jim Carrey’s work, I would urge you to go watch The Mask, or Dumb and Dumber, or The Truman Show, or Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, or the acerbic and underrated I Love You Phillip Morris. If you are already fond of Jim Carrey, re-watch them—give The Cable Guy another shot, too—and wait for a proper memoir or the thoughtful biography he deserves.

Bruce Handy is a journalist and the author of Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult