The Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) has been called the first modern conflict. This is no compliment. Few emerge from the pages of its bloody, cynical history with much credit. Not the “prime instigators,” diamond baron Cecil Rhodes and Dr. Leander Starr Jameson (of Scholarship and Raid fame, respectively). Nor its British officials and generals, the High Commissioner Alfred Milner and Lords Roberts and Kitchener and Redvers (“Reverse”) Buller. The put-upon Boers were, for their part, proud, determined—and, like many of their antagonists, incurably racist.

A forward-looking view of the war—the dawn of mass-media coverage, barbed wire, and concentration camps—emphasizes the bit parts played by 20th-century personages. Winston Churchill, the neophyte correspondent, making his daring escape from Boer captivity; Mohandas Ghandi’s exertions in the Indian ambulance corps; and Robert Baden-Powell’s devil-may-care dispatches from the Siege of Mafeking (“One or two small field guns shelling the town. Nobody cares”; “All well. Four hours bombardment. One dog killed”), which prefigured his Boy Scout movement by 10 years. Sarah LeFanu’s Something of Themselves takes the opposite tack, tracing the lives of the Victorian—in sensibility if not wholly in fact—writers Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Mary Kingsley as they intersect in South Africa in the war.

Something Old, Something New

LeFanu’s title derives from Kipling’s posthumous memoir, Something of Myself (1937), channeling the reticence and “refusal to reveal everything” common to all three. Kipling was born in 1865 in Bombay. A “Raj orphan,” he spent five harsh, formative years boarding in Southsea at the “House of Desolation” (he was punished for, among other things, shortsightedness—“taken as a sign of his ‘showing-off’”—and reading) and another five at the United Services College. The latter spell shored up his adolescent confidence and shaped the “Stalky” tales of the 1890s—“very readable, very funny, and at times quite surprising” in LeFanu’s spot-on appreciation.

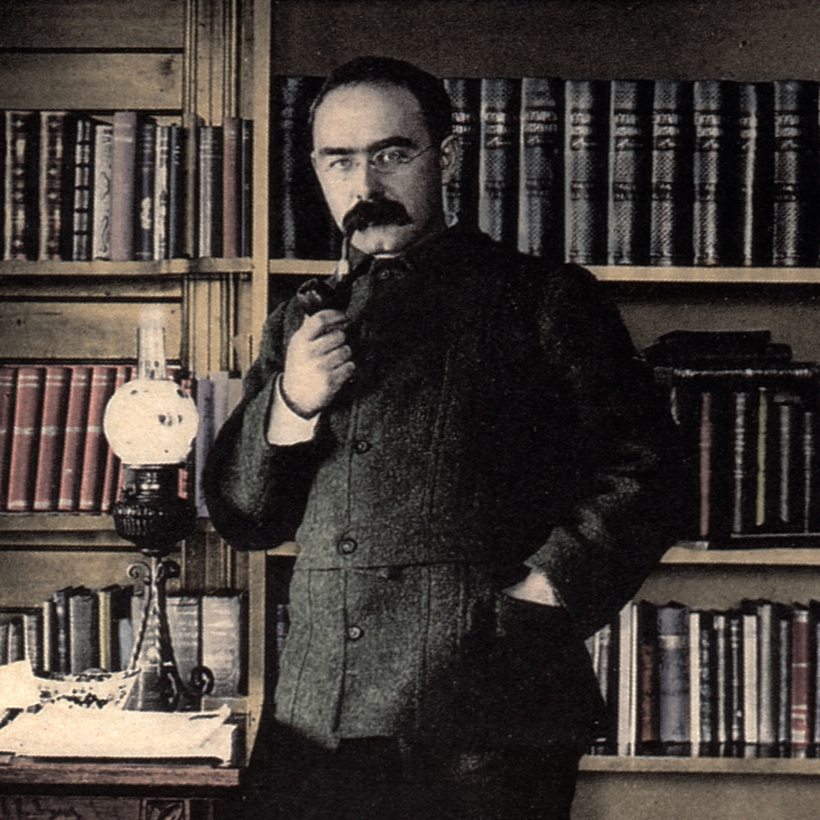

Kipling returned to India at age 16 as sub-editor of Lahore’s Civil and Military Gazette, tossing off finely observed stories and well-turned verse. In his early 20s, he left again for London, traveled the world, married (Henry James gave the bride away), settled for four years in Vermont—producing the Jungle Books (1894–95), Captains Courageous (1896), and the first draft of Kim (ultimately published in 1901)—and acquired considerable literary fame, not least for the Jubilee-themed “Recessional” (1897) and equally topical “The Absent-Minded Beggar” (1899). An admiring friendship with Rhodes fired his imperial imagination. The death, in March 1899, of his beloved six-year-old daughter, Josephine, unmoored him. By his expedition to Cape Town in January 1900 as “propagandist-at-large,” he was “on friendly terms with the big noises in British and colonial circles” and, LeFanu notes, had already spent time with Conan Doyle, over golf and “high converse,” and Kingsley, both (likely) in 1894.

LeFanu’s title channels the reticence and “refusal to reveal everything” of her central subjects.

Conan Doyle overcame his father’s alcoholism and the “weary grind” of medical studies at Edinburgh—his professor Dr. Joseph Bell’s “extraordinary powers of observation would feed into the creation” of Sherlock Holmes—before establishing his own practice in Kipling’s dreaded Southsea, where “a man falling off his horse outside the front door and being carried inside … [marked] the increase of patient numbers by 100 per cent.” He kept busy, he assured his doting mother, by “tending my little literary sprouts and making them into cabbages.”

The apathetic doctor wed in 1885 and, subsequently, “in the gaps between his consultations and during quiet evenings at home,” altered the course of detective fiction with A Study in Scarlet (1887; the original version, A Tangled Skein, featured one “Sherrinford” Holmes). The Sign of the Four (1890), and the Adventures (1891–92) and Memoirs (1892–93) of Sherlock Holmes cemented his reputation. Conan Doyle killed off the public’s lucrative favorite at the Reichenbach Falls in 1893, lest he become “entirely identified with what I regarded as a lower stratum of literary achievement.” It would be eight years until he revisited his exploits in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1901). Months after Holmes’s plunge, Conan Doyle’s wife, Touie, was diagnosed with consumption. Desperately torn between fidelity to Touie and feelings for Jean Leckie, the woman who would replace her, he volunteered for John Langman’s private field hospital in South Africa in 1899. His departure preceded Kingsley’s by one month.

“Where on Earth Am I to Go?”

Kingsley was nothing if not original and someone I would dearly like to have met. She spent her teens, LeFanu recounts, acting as her egomaniacal physician-adventurer father’s “secretary and assistant, sorting his notes, helping to classify his specimens” and learning German “so that she could translate what he needed for a proposed work on sacrificial rites.” He died in 1892, bequeathing his wanderlust and £8,000, to be shared with Mary’s ill-deserving younger brother, Charley. She heeded the call of “science” to “learn your tropics”: “Where on earth am I to go? I wondered, for tropics are tropics, wherever found; so I got down an atlas and saw that either South America or West Africa must be my destination, for the Malayan region was too far off and too expensive.” Africa it was. Owing to “the high attrition rate amongst Europeans,” her liner sold only one-way tickets.

She kept up appearances (“You have no right to go about in Africa in things you would be ashamed to be seen in at home”) but roamed with economy, carrying “spare clothes, along with a blanket, a copy of Albert Günther’s An Introduction to the Study of Fishes and her well-thumbed copy of Horace’s Odes, and some notebooks and nets and collecting jars.... About her person she kept a small knife and a revolver (for brandishing rather than shooting).” Hers was the empiricism of the century’s finest explorers: “One by one I took my old ideas derived from books and thoughts based on imperfect knowledge and weighed them against the real life surrounding me, and found them either worthless or wanting.” She distilled her experiences and lightly worn expertise into the magical Travels in West Africa (1897). Kingsley’s sangfroid in the bush has always reminded me of Aunt Dot in The Towers of Trebizond (1958), the final novel of LeFanu’s earlier biographical subject, Rose Macaulay—minus the rumors of espionage and autumnal romance. (See Mary fending off crocodiles and leopards with paddles and pots and Dot’s pragmatic brush with cannibals.)

“One by one I took my old ideas derived from books and thoughts based on imperfect knowledge and weighed them against the real life surrounding me, and found them either worthless or wanting.”

In March 1900, Kingsley followed Kipling and Conan Doyle to South Africa to nurse beleaguered soldiers. For LeFanu’s stoic trio, the war—the reporting of which is drawn largely from Thomas Pakenham’s grand, stylish The Boer War (1979)—proved alternately disillusioning and tragic. Kipling would come to lament the Empire’s “political suicide” and, in LeFanu’s words, mourn South Africa as “another locus of loss.” Conan Doyle’s account, The Great Boer War (1900), was profitable—and hopelessly ephemeral, reaching readers two years before the war’s conclusion. Kingsley succumbed to typhoid within three months of her arrival. Per her wishes, she was buried at sea.

From these disparate parts, Something of Themselves makes for elegant and moving group biography, remedying various degrees of neglect and misjudgment. Kingsley has been overlooked, Conan Doyle overshadowed, and Kipling deplored—though never forgotten. His moral and spiritual lessons from the war live on in the stirring conditionals of “If” (1910), which were inspired not by the pluck of the Boers but by his friend, their bogeyman, Dr. Jameson.

Max Carter is the head of the Impressionist and Modern Art department at Christie’s in New York