Don’t judge Jenny Finney Boylan’s newest nonfiction book by its cover. Yes, it features a photograph of an obedient, adorable dog—shot from above, head slightly cocked with concern and attention—but Good Boy is so much more than a mere “dog book.”

Boylan has published three previous memoirs that explore her life in two genders: She’s Not There, I’m Looking Through You, and Stuck in the Middle with You. But in Good Boy, Boylan’s dogs offer signposts pointing her toward a greater understanding of herself. From a childhood as Jimmy to an adulthood as Jenny, dogs have accompanied her through the shifting landscapes of her well-charted life.

Top Dog

Good Boy was born out of an opinion piece Boylan wrote in December 2017 for The New York Times about losing her dog Indigo. The piece was, in Boylan’s words, her offering to the annual, year-end news cycle, “stories about lives that came to an end during the year and remember small acts of grace—those gifts that cannot be asked for, only received.”

The piece went viral because it hinted at something deeper than an anecdote about Boylan’s love for a rescue dog with a “wise, droopy face and swinging dog teats.” The essay was the germ of a book, a longer, more nuanced story waiting to be told about the way dogs shape our lives as they bear witness to our evolving humanity. When these witnesses die, Boylan writes in that essay, “you not only lose the animal that has been your friend, you also lose a connection to the person you have been.”

The author’s dogs offer signposts pointing her toward a greater understanding of herself.

Boylan is a skilled writer of both fiction and nonfiction, but she writes Good Boy in an especially confident voice. Her narrative travels great distances between ages, stages, and dogs; she zigs, then zags, chasing down one memory before changing direction to pursue another. Boylan races along with an impatient yearning, only to pause and note an interesting moment along the way. After a moment of reflection, she turns her attention elsewhere, doubling back when she’s gained enough years and perspective to understand what she missed the first time around.

Patient readers will be rewarded for sticking with Boylan, for just when you think you’ve lost sight of her point, she slows her pursuit, lingering on moments so beautiful and true they demand to be read twice:

In normal circumstances, Lucy had nothing but contempt for signals of command. But the dog seemed to sense that these circumstances were not normal. The dog sat down and looked at me uncertainly.

I will be staying here, she said.

“I’ll be back,” I said to the dog.

Lucy wasn’t sure about this.

Will you? she said.

In the flap copy of her book, Boylan claims, “Everything I learned about love I learned from dogs,” and her exploration of this territory is some of the most satisfying in the book. From her relationship with her father to the education she gained from college affairs, her enduring marriage, and her deep love for her children, Boylan searches out the moments of truth and uses that truth to help her understand the nature of love itself.

Sly Dog

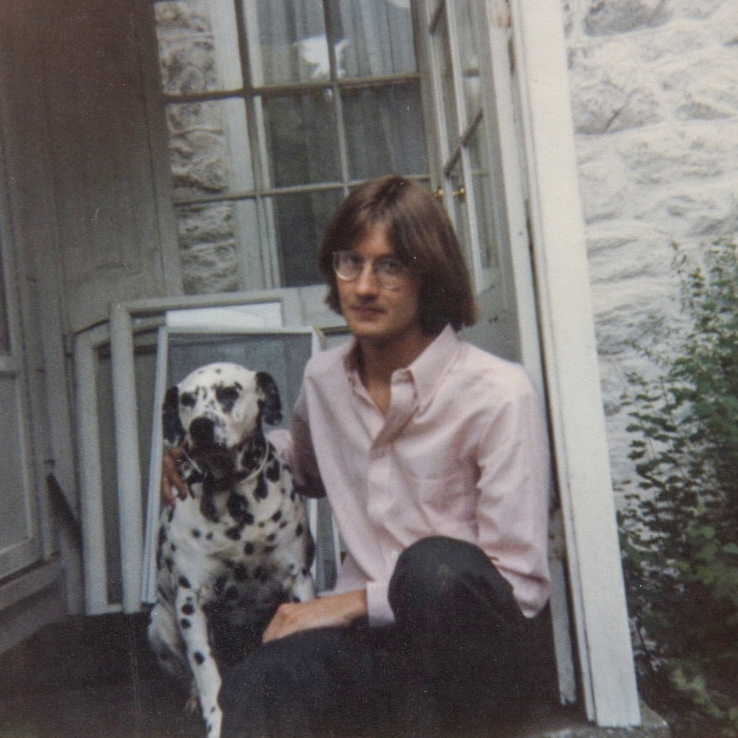

Boylan has been concealing her secrets and searching for answers her entire life. She’s looked inside the “ROBOTRON 9000 THE ANSER MACHINE” she built when she was a boy named Jimmy with a Dalmatian named Playboy. Jimmy and Playboy climbed into that box, booted up the system, and waited for the questions—and their answers—to arrive.

“Jimmy,” my mother said, “come out of the box.”

“Boing,” I replied.

“I’ll write down some questions,” my father told her, as if to say, I’ll handle this.

There was a long pause. I looked down at my feet at Playboy. He growled resentfully, to let me know—as if I didn’t already—that this whole enterprise was doomed.

However, when the ROBOTRON 9000 THE ANSER MACHINE failed to provide answers to life’s big questions, the dogs did. When no one suspected what “nuclear secret” Jimmy-who-yearned-to-be-Jenny was hiding, the dogs knew. When he feared he was a bad boy, the dogs knew better.

When mean dogs snarled, it was because they saw into Jimmy’s heart (“I know who you are”) and called him out on his lies (“You are not you”). When Boylan asks, “What is this world? What is this life?,” her dogs provided the answer. When Boylan was incapable of searching for her true self any longer, the dogs reminded her that she was not lost.

“Everything I learned about love I learned from dogs.”

Boylan’s dogs dutifully lead her back to her best self, a self she describes as canine in nature. “But I have been drawn to dogs above all, perhaps because my own personality is fundamentally canine. I am happiest when I am with those whom I love, preferably by a warm fire. If you lost something, I would try to bring it back to you.”

Good Boy is a delightful, challenging read, and a lovely addition to Boylan’s body of work. To remain relevant and fresh, memoirists must push beyond the usual narrative rules and find new ways to uncover truths. Boylan’s dogs offer a way into her truest story: a quiet, searching gaze that demands honesty, a soft ear that provides comfort, and a reassuring closeness that grants stability and love. A great memoir provides a path forward for the reader as well as the writer, and Good Boy does just that. As Boylan discovers who she is through her dogs and her stories, her writing brings us back to ourselves, too.

Years ago, Boylan was accepted to the graduate writing program at Johns Hopkins by way of a phone call from the writer John Barth. He told Boylan, “We were all impressed with the felicity of your invention,” and once you’ve read Good Boy, you will be, too.

Jessica Lahey is the author of The Gift of Failure