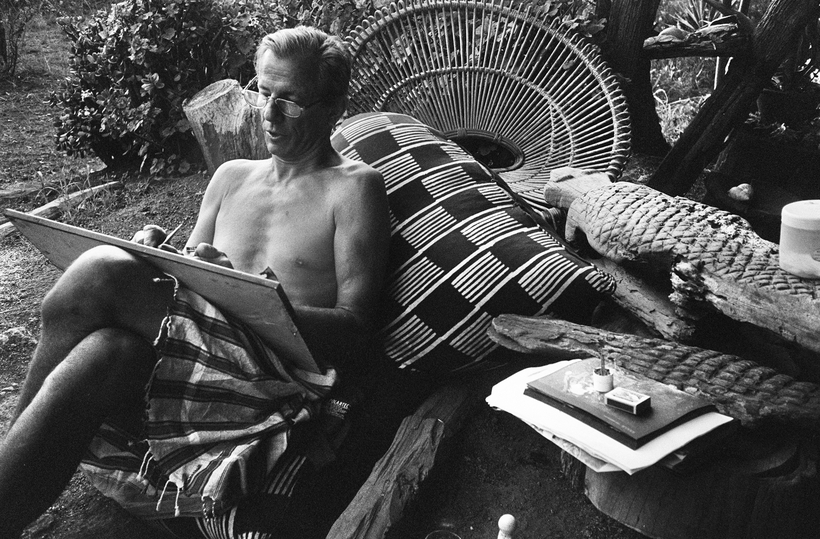

When I first heard Peter Beard had disappeared I laughed out loud.

I’d immediately assumed he’d managed to jump over the fence at his sprawling Montauk estate and escaped into Manhattan to go clubbing again. He’d done it before, and anyone who knows him will tell you that even in his diminished state, in his 80s, his instinctive wildness, his reflex flirtation with recklessness, would have him do it again.