In 1916 a young woman named Madge bet her sister that she couldn’t write a detective novel. Unfortunately, her sister was Agatha Christie so she lost. The novel Madge’s bet inspired was Christie’s debut, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, which was first published in serial form in The Times starting this week a century ago.

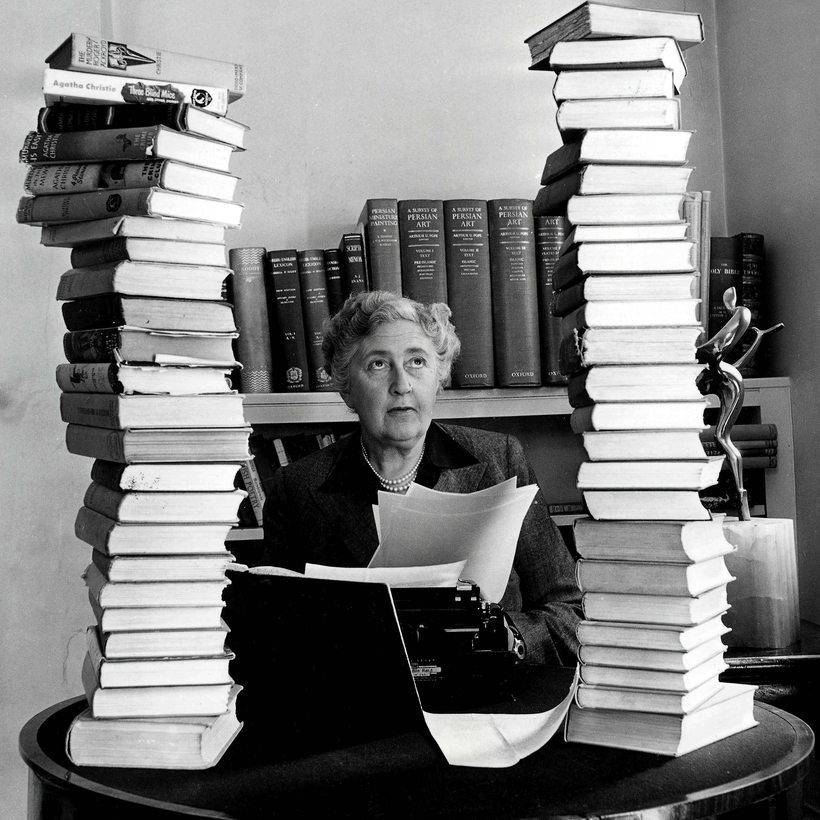

Few bets have been lost as spectacularly as Madge’s. Christie went on to write 66 detective novels, as well as 14 short-story collections. Two billion copies of her books have been sold, making her the most commercially successful novelist yet. She is the third most widely published author in the world (after Shakespeare and the Bible) with her works appearing in 104 languages. Almost all her books have been adapted for television, radio or film.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles has none of the faltering confidence or hesitation of a debut. Reading it you think: here is an author finally doing what she was born to do. Typically for Christie, the novel proceeds at a clip. She spends only 29 pages briskly arranging the basic structure of the detective puzzle: the country house, the rich older woman, her gold-digging younger husband, her children from a previous marriage. Captain Hastings arrives, there are a couple of Chekhov’s gun-style conversations about poison and we are briefly introduced to Hercule Poirot. Then, on page 30, news of the murder.

Mrs Inglethorp, the rich older woman, is having a fit in her bedroom. Her eldest son, John, pulls Hastings out of bed and they break down the door, at which moment Mrs Inglethorp neatly dies. Poirot is summoned and the work of detection begins. The clues accumulate: strychnine on the cocoa tray, a fragment of a burnt will, a smashed teacup, a wax stain on the carpet. Motives proliferate too: who stood most to gain from Mrs Inglethorp’s death? Her new husband, Alfred? Or her eldest son, John?

Two billion copies of her books have been sold, making her the most commercially successful novelist yet.

Already this first novel is an archetypal Christie: the country house, the elaborate red herrings, the drawing room denouement, and of course the character of Poirot, who appears fully formed with his “very stiff and military moustache”, inflated dignity and irritatingly redundant Gallicisms (“Not so. Voyons”… “en voilà une table” and so on).

Readers come to Christie early. I raced through the Poirot books when I was 11. Christie’s great-grandson James Prichard tells me he read his first at the age of eight (although a precocious knowledge of her works must have been de rigueur in that family). It might be surprising that novels about murder should be so popular among children — or, rather, surprising that parents should tolerate that popularity. But as Prichard points out, there’s no great sense of threat or horror. This is not the world of Jo Nesbo or Ian Rankin.

In The Mysterious Affair at Styles Christie reassures her readers that there is nothing upsetting about Mrs Inglethorp’s death, which is “a shock and a distress, but she would not be passionately regretted”. At dinner later that day, Christie is careful to note, “there were no red eyes, no signs of secretly indulged grief”. In this novel the murder is the occasion of more fun than sadness. Stalking around the dead woman’s bedroom, Poirot “laughed with apparent enjoyment”, Hastings is full of “pent-up excitement” at the discovery of strychnine crystals, and Annie, the dead woman’s maid, is “labouring under intense excitement, mingled with a certain ghoulish enjoyment of the tragedy”. Just like Christie’s readers.

Her works appear in 104 languages. Almost all her books have been adapted for television, radio or film.

Christie had little talent for or interest in characterisation. Her memoirs are notable for their lack of introspection. It is perhaps significant that Christie claimed to have no memory of the most significant emotional experience of her life — her famous week-long disappearance after her husband announced he was in love with another woman. Christie’s thin characterisation is the aspect of her work that has attracted most hostility from critics. In his 1945 essay Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd? Edmund Wilson complained that in Christie’s books “you cannot become interested in the characters, because they never can be allowed an existence of their own even in flat two dimensions”. It is hard to dispute that point, although many readers will not care.

One character even irritated Christie herself: Poirot. The detective was, she said, “regarded perhaps with more affection by outsiders than by his own creator”. She was compelled to go on writing Poirot novels (there are 33 of them, as well as 51 stories) because he paid the bills. Readers loved Poirot so Christie was chained to him. Asked what advice she would give to a writer starting out in detective fiction, she warned: “Be very careful what central character you create — you may have him with you for a very long time!”

In his brilliant essay on Christie’s novels (for my money the best thing written about her) John Lanchester provides a masterly deconstruction of the character of Poirot. He is, Lanchester contends, “the worst detective of all… [the] least likeable, most implausible, most annoying, vainest, and the one whose characterisation is most dependent on whimsical details that add nothing in terms of psychological insight”.

Christie claimed to have no memory of the most significant emotional experience of her life — her famous week-long disappearance after her husband announced he was in love with another woman.

Poirot appeals, Lanchester argues, precisely because he is so unbelievable. Christie’s novels are formal puzzles and “readers understand and resonate to the profoundly artificial, conventional nature of Christie’s fictions; Poirot is understood and accepted, indeed actively enjoyed, as a formal device”.

I think that’s spot-on. Poirot’s almost-mechanical nature is evident immediately in The Mysterious Affair at Styles. He is a caricature from the beginning, with his head that is “exactly the shape of an egg”, his “stiff” moustache and clothes so neat they seem “almost incredible”. The humour of Poirot is the humour of an overzealous robot: his obsessive tidiness (he compulsively picks up odd matches and bits of rubbish), the mechanical finesse of his movements (evidence is always seized with tweezers and stored in little envelopes; he’s always flourishing his hat). He has always reminded me of C-3PO from Star Wars.

Christie’s novels are puzzles. This is their appeal. The country house in The Mysterious Affair at Styles is not so much a place to be dwelt in by humans as a chessboard or perhaps a game of Cluedo. Poirot is wound up like a clockwork animal and dispatched to skitter off through the maze with his tweezers and neat remarks. We never doubt that he will complete his journey impeccably.

Christie seems to have had few illusions about this aspect of her fiction. She’s always hinting at Poirot’s methodical, robotic nature (“ ‘A man of method’ was, in Poirot’s estimation the highest praise that could be bestowed on any individual”). She remarked of her novel And Then There Were None (in which all the characters but one are murdered) that it was a “technical extravaganza”. Christie’s work has never gone out of fashion because puzzles don’t date the way novels do; The Times has been publishing crosswords for almost a century.

The timeless appeal of her fiction meant Christie was able to go on writing well into old age. The public’s lust for Poirot was never sated. Christie must have sensed that she had found her vocation with The Mysterious Affair at Styles as she rushed eagerly into a disadvantageous publishing contract with Penguin that promised royalties of 10 per cent only after she had published 2,000 copies and which locked her in for six books.

Times readers, who are discerning people, were the first to get their hands on the story, which was serialised in the paper’s weekly edition for overseas readers. It was the first time a debut novel had been chosen for this honour. It seems fitting that an author who would be so widely translated was first read across the world in every corner of the British empire from Australia to Africa. It was another year before The Mysterious Affair at Styles appeared in book form, but it received enthusiastic reviews and the 22-year-old Christie was set.

Poirot made his last appearance in 1975, a few months before Christie’s death. That extraordinary career was all down to her talent, of course, although it’s pleasing to think that that first nudge from the Thunderer helped her on her way.