It’s 1968 all over again. That’s been the familiar 2020 refrain, and it makes a certain sense. It was a tense election year, rife with mass protests in response to racist misdeeds, escalating inequality, and law-and-order rhetoric. There also happened to be a flu pandemic that year that killed roughly 100,000 Americans.

The news headlines of 1968 and 2020 might rhyme, but Eric Burns’s 1957: The Year That Launched the American Future suggests a more intriguing comparison point: 1957. That year was defined by more than one failure, the first postwar moment when America was forced en masse to confront its fallibility. And it contained the seeds of the 60s, and in turn our current existential crisis.

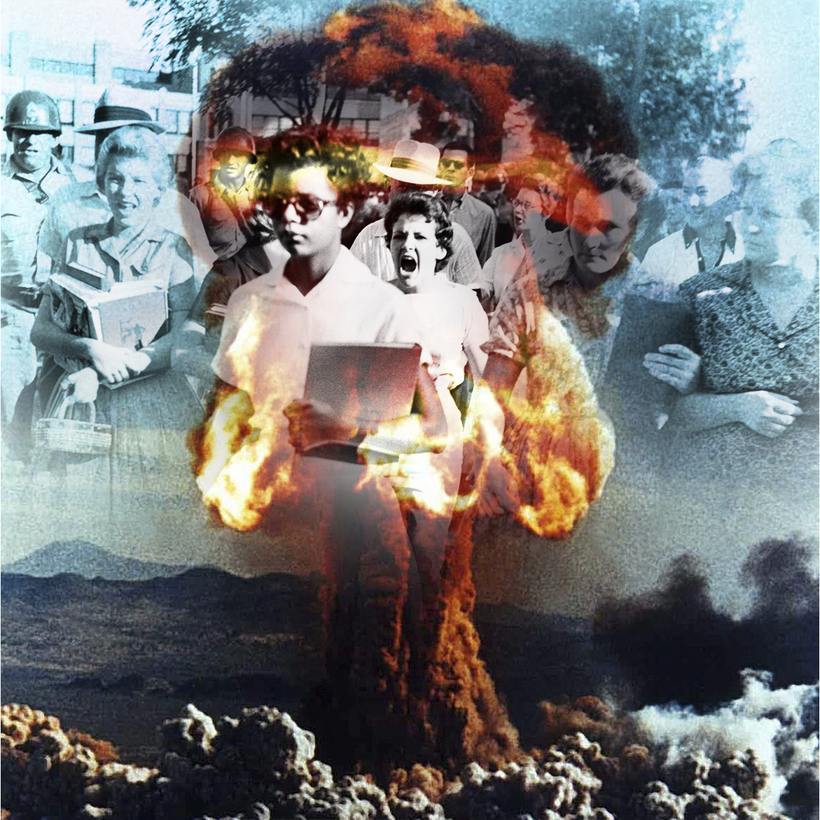

If you’d squinted into the evening sky that year, you might have seen it wink back at you. Sputnik, launched by the Soviets on October 4, 1957, was the first orbiting space satellite, and it set America into a state of high-grade status anxiety. (It also frightened Little Richard enough to quit rock ’n’ roll and “go back to God.” In retrospect, this may have been the greater national crisis.) The U.S.’s own rockets, hastily built to catch up, mostly collapsed on the launchpad, and with every failure, Burns writes, “we succeeded only in humiliating ourselves while the whole world watched, snickering at the arrogance of capitalism.” (More covertly, the United States was aggressively perfecting its nuclear-weapons capability through a series of tests in the Nevada desert called Operation Plumbbob.)

The year 1957 was defined by more than one failure, the first postwar moment when America was forced en masse to confront its fallibility.

The 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air was the high-water mark of tail-fin-era car design, and thanks to the previous year’s Federal Aid Highway Act, there were fresh roads for the cars to cruise on. But the year also coughed up the Ford Edsel, a homely, mechanically balky sedan that failed despite a splashy TV promotion featuring Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, and Rosemary Clooney. The clunky name—a tribute to Henry Ford’s son and the result of much searching on the part of Ford execs, who recruited modernist poet Marianne Moore for ideas—would turn out to be the least of the car’s problems. (Among Moore’s unused suggestions: Andante con Motor, Varsity Stroke, and Utopian Turtletop.)

The bum car was a symbol for the year’s other breakdowns. George Metesky, a malcontent who’d littered New York City with pipe bombs to protest his firing by Con Ed, was captured in 1957, inspiring future would-be Weathermen. Congressional investigators threw harsh light on union leaders, especially Jimmy Hoffa, the incoming head of the Teamsters. Senate scrutiny, Burns writes, delivered “one of the most explicit and necessary awakenings that Americans ever have had about the excesses of Big Labor, peeling away layer after layer of seeming respectability.” Mobsters were caught trying to convene in Apalachin, in upstate New York, but the authorities weren’t able to parlay it into the breakup of the Mafia.

Cuba began to slip into Castro’s hands. The Dodgers left Brooklyn. And in Little Rock, Arkansas, the 15-year-old Black high-school student Elizabeth Eckford was stymied in her first attempt to enter a newly integrated school.

1957 All Over Again

Burns, a media critic and former NBC News correspondent, doesn’t have an explicit theory of 1957 to proffer—his book is pop history, cannily blending the perspective of a grizzled journalist with glints of nostalgia. But the clear message of the book is that the center wasn’t holding. The Western escapism on TV (Gunsmoke) and re-litigation of World War II glories in theaters (The Bridge on the River Kwai) belied emerging ideological fault lines that would widen in the coming decades.

Ingeniously, Burns connects chapters about Billy Graham’s 97-day run at New York stadiums with the publication of Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, twin milestones for evangelicals and libertarians. “The only person with a drawing power comparable to Ayn Rand in 1957 was probably Billy Graham,” Burns writes. Even if that isn’t so—Elvis? Sinatra?—Burns is right to suggest that both tapped into a deepening discomfort that suburbia might paper over but not assuage.

The space race of 1957 frightened Little Richard enough to quit rock ’n’ roll and “go back to God.” In retrospect, this may have been the greater national crisis.

Still, Burns does make some peculiar leaps of reasoning. He is curiously approving of Rand’s Atlas Shrugged (“always worthy of discussion, always deserving of attention”) while condemning Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, even as an influential novel. (“The author’s style seems a disguise for the absence of meaning.”) Looking for a 1957 film that exemplifies the fractured American psyche of the era, he arrives at … I Was a Teenage Werewolf. (A Face in the Crowd, 12 Angry Men, even Peyton Place might have made for better alternatives.)

Most cringingly, Burns sifts through the most popular songs by Black artists in 1957 and categorizes Elvis as Black, “which, both musically and in terms of the amount of vituperation he received, is where he belongs.” It’s an argument as specious as it is unnecessary: Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Sam Cooke, and Little Richard were evidence enough of pop music’s deepening integration without requiring Presley in blackface.

Burns’s main point obtains, though: beneath the surfaces of American can-do productivity, divisive rhetoric, ideological splits, and structural flaws were beginning to win the day. Today, MAGA hats are a balm to people who want to imagine a fantasized past when America thrived. And 1957, the year many boomers came of age, seems as good a place as any to pinpoint the origins of that fantasy. But even Burns’s casual look beneath the surface reveals a host of disintegrations and delayed reckonings, ones that have lasted to this day.

Mark Athitakis is the author of several books, most recently The New Midwest: A Guide to Contemporary Fiction of the Great Lakes, Great Plains, and Rust Belt