In London …

From Dr. Strangelove to Doctor Zhivago?

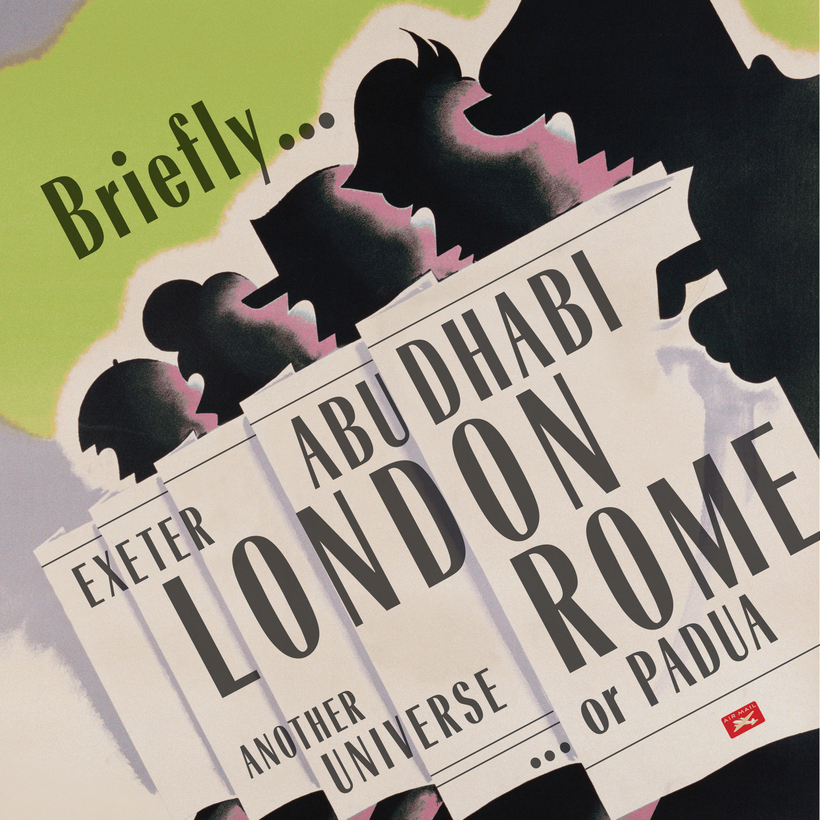

Stanley Kubrick made only 13 feature films, so every time another might-have-been comes to light, film buffs get all wistful and agitated. (And just try doing that simultaneously.) Perhaps most significant among the unmade Kubricks are a biopic of Napoleon and one movie that eventually did get made, by Steven Spielberg: A.I. Artificial Intelligence. Now we must reckon with the notion of an alternate-universe Doctor Zhivago, because, as the British film historian James Fenwick has discovered, Kubrick and Kirk Douglas—who had worked together on Paths of Glory—tried to buy the movie rights to the Boris Pasternak novel in the late 1950s, soon after it was published.

Fenwick, in the course of researching a book, found a letter Kubrick had written to Pasternak making his case and, according to The Guardian, also discovered a passage in one of the director’s notebooks in which Kubrick noted, “The precise moment of absolute success for a director is when he is allowed to film a great literary classic of over 600 pages, which he does not understand too well, and which is anyway impossible to film properly due to the complexity of the plot or the elusiveness of its form or content”—a surprise to Fenwick, as Kubrick was at that point in his career “more associated with pulp crime fiction” than with “literary classics.” Kubrick and Douglas were unable to secure the rights, and the film was eventually made, in 1965, by David Lean. Kubrick fans are left to wonder, What if…?Though Omar Sharif fans are probably breathing sighs of relief.