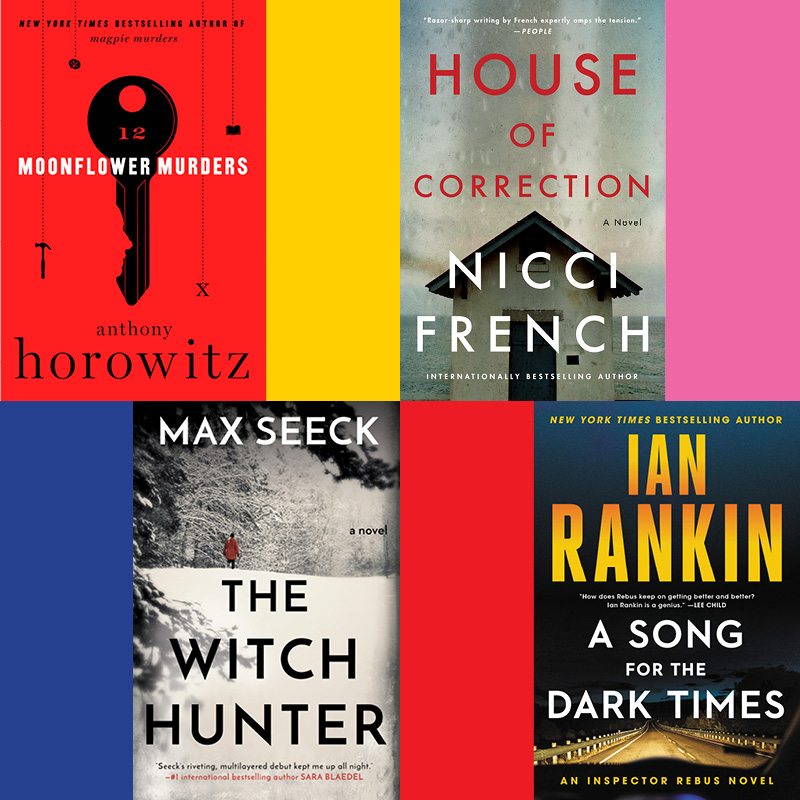

“The act of editing, like the act of writing, is so intensive and occasionally so fraught with problems that no matter how pleased I might be with the finished product, I’m always happy to put it behind me. I don’t need to go back.” And yet the editor and occasional detective Susan Ryeland does go back, in this sequel to Anthony Horowitz’s wonderful Magpie Murders (2017), to try to solve another mystery. She’s been running a hotel in Crete—not too successfully—when the parents of a missing young woman track her down. They think that a book Ryeland edited by mystery writer Alan Conway (who was killed in Magpie Murders) contains crucial clues to her disappearance, and beg her to help them find their daughter. Some years earlier, Conway stayed in the couple’s hotel in Suffolk, where a friend of his had been killed. He borrowed liberally from his experience there to write Atticus Pund Takes the Case, which the parents believe points the finger in some coded literary fashion at the friend’s killer, who may have taken their daughter.

Ryeland agrees to help and returns to England. As she revisits the book, which she’s completely forgotten, we get to read it with her—Horowitz has written an entire book within a book. If you’re game to troll for clues, a little knowledge of astrology, opera, and Shakespeare will help, along with a knack for wordplay, anagrams, and spotting Easter eggs (little messages to the astute reader).