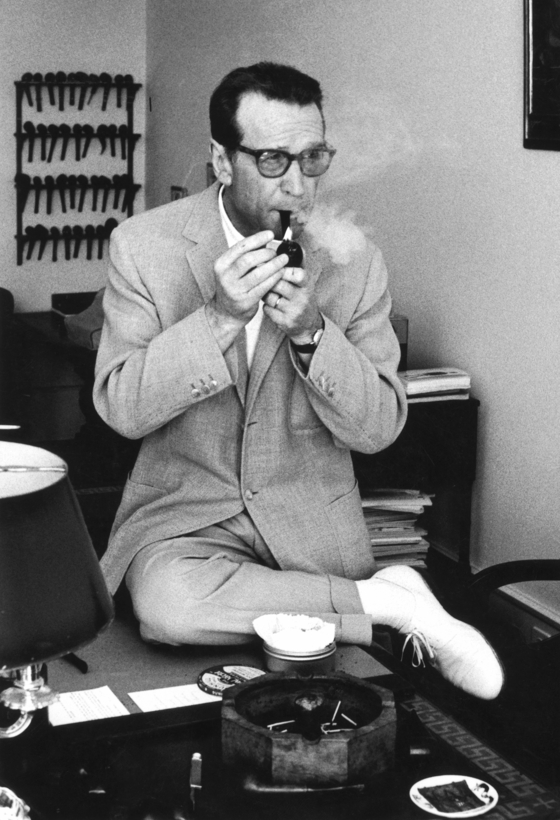

If you threw a party for literature’s greatest detectives, from Sherlock Holmes to Easy Rawlins, it’s a safe bet that Inspector Jules Maigret would be far from the center of attention. Maigret, the star of 75 novels by the Belgian-born writer Georges Simenon, doesn’t perform flashy feats of deduction, wield the latest forensic gadgets, or chase criminal masterminds through waterfalls. He is a hulking, taciturn, middle-aged man who is almost always to be found either eating, drinking, or smoking his pipe. At night he sometimes goes to the movies with his wife, who after decades still calls him by his last name. He’d probably take one look around the party and slip away to his favorite bistro, the Brasserie Dauphine, just down the street from his office at Quai des Orfèvres, the headquarters of the Police Judiciaire.

So, what makes Maigret a favorite detective of so many literary writers and readers, from William Faulkner and André Gide in the 20th century to David Hare and John Banville today? The secret is that Maigret himself is almost a novelist—one who turns his gifts of imagination and empathy to solving crimes rather than writing books.