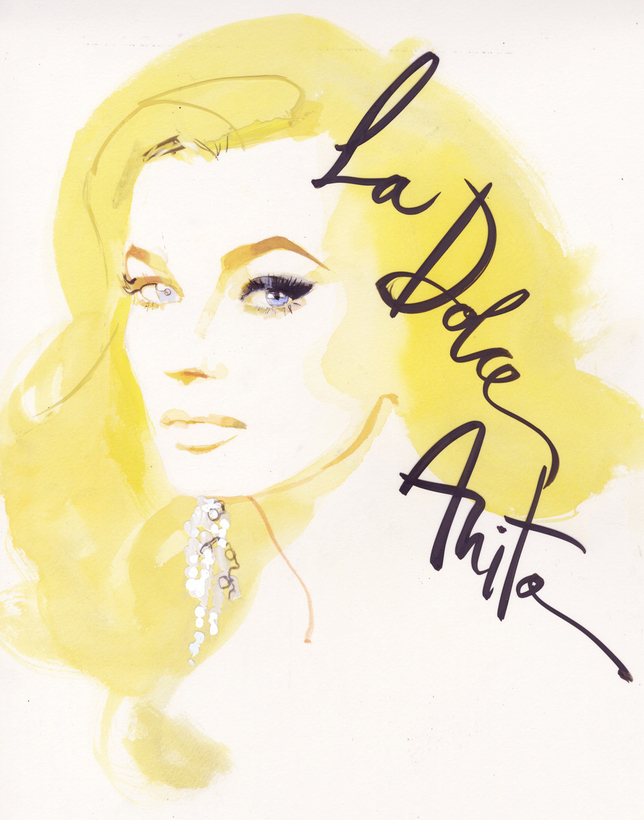

“Marcello, come here!” coos movie star Sylvia Rank (Anita Ekberg) to the reporter–gossip columnist Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni) as she wades around the Trevi Fountain under a silver gelatin moon, in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960). Her dress, cut low and hitched high, unfurls in the water like ink. The cascade goes silent. Nino Rota’s haunting score floats into the air. It is one of the unsurpassable moments in cinema, and with it Anita Ekberg entered into myth.

She was born in Malmö, in 1931, one of eight siblings. At 20, she won the Miss Sweden beauty pageant, a title that brought her to America and to the attention of Howard Hughes. But Ekberg balked at his suggestion that she change her name, her nose, and her teeth and returned home. But soon, she was back in Hollywood and under contract, first to Universal and then to John Wayne’s production company, Batjac. If movies found little for her to do (she was “Vesuvian Guard” in Abbott and Costello Go to Mars and a Chinese peasant in Blood Alley), rapturous layouts in Vogue and Esquire by the glamour photographers Peter Basch and Andre de Dienes highlighted her statuesque Nordic splendor and propelled her to a parallel, pinup stardom. She was known as “the Iceberg,” “the Blonde Venus,” and “the girl who makes Jane Russell look like a boy.” The scandal sheets meanwhile kept a boldfaced tally of her affairs with Tyrone Power, Gary Cooper, Frank Sinatra, and Yul Brynner.