When the body of Peter Farquhar was found in October 2015, slumped on his couch with a bottle of whiskey beside him, those who knew him were saddened but few were surprised. An inspirational English teacher to generations of pupils, the 69-year-old had grown noticeably feeble. His usually sharp mind had been blunted by age and, it was said, perhaps a little too much drink. The coroner agreed and blamed his death on “acute alcohol intoxication.” His funeral was attended by former colleagues and students and was a sad but affectionate affair. There was talk of his eloquence, his wit, and his glorious passion for teaching. His young partner of recent years, Ben Field, read the eulogy. The Guardian published a glowing obituary, an unusual tribute for a schoolteacher. But if his job was modest, his influence was powerful. Farquhar had taught me for four years when I was a teenager in the mid-1990s, and I can still see his fingerprints on my character and interests more than 20 years later. His death felt like that of a family member. So it was a shock when I began to hear rumors last year that he may not have died a natural death at all.

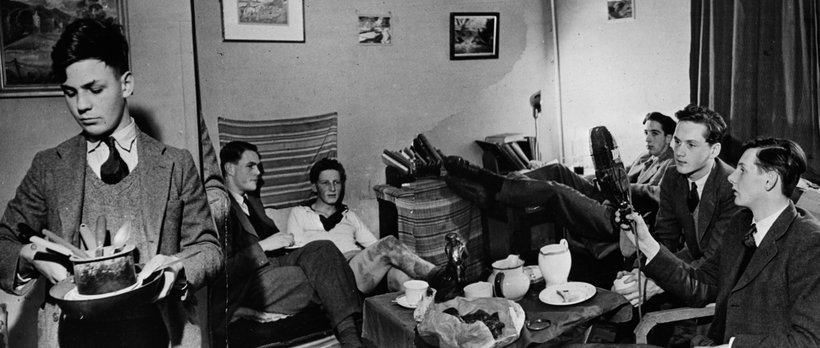

Farquhar had taught at Stowe School in England, which was founded in 1923. Occupying what was once a majestic, 18th-century, neoclassical stately home of golden stone colonnades and soaring Corinthian columns, it sits amidst hundreds of acres of sweeping lawns, limpid lakes, and wildflower meadows spotted with temples, statues, and other purely decorative follies. Designed by the great landscape architect Capability Brown, the gardens are a master class in concealed artifice. Their seemingly wild expanses are the result of hidden walls, or “ha-has,” that separate the fields and invisible dams that form the lakes. Walking in the school’s gardens is like entering a Renaissance painting. The grounds are what we think nature should be, rather than what it is.